Rabbi Chaim Druckman, this year’s winner of the Israel Prize for Lifetime Achievement, the country’s highest honor, raised some eyebrows this week with his dismissal of the Israeli government’s decision last week to, for the first time, recognize Conservative and Reform rabbis.

The move, by Israel’s attorney general, not only recognizes them as rabbis but also pays 16 of them who work in rural settings.

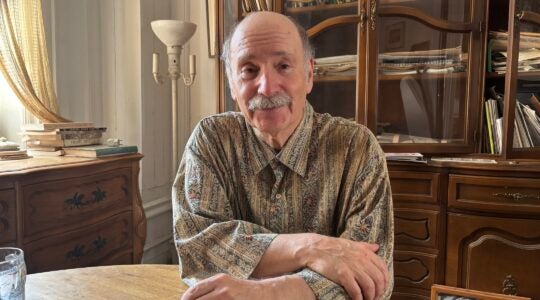

“I have nothing against the state giving pay to people who do something for other people,” Rabbi Druckman said during an interview Monday at the New York offices of The Jewish Week.

“But you don’t speak here about rabbis — they are not rabbis and the state realizes they are not rabbis because they will get their salary through the Culture Office and not the Minister of Religious Services.”

Asked whether that move wasn’t because Yaacov Margi, the Orthodox minister of religious services, threatened to resign if the money came from his office, Rabbi Druckman replied: “No, the state realized they are different; they are not rabbis. They should be equal and get paid — different people who help others also should be paid — but as individuals who are working and not as rabbis.”

The rabbi’s comments were seen as surprising to some because of his progressive views on other matters. In 1990, for instance, he was a founder of the hesder yeshiva program that allows religious young men to combine Torah studies with army service. Until earlier this year, he served as director of the state’s Conversion Authority that educates candidates for conversion to Judaism, including many immigrants from the former Soviet Union.

He believes also that all of the West Bank and Gaza is part of the land of Israel and thus opposes dividing it into Israeli and Palestinian states. But at the same time, he ruled that a religious soldier had to obey orders to remove settlers from West Bank villages if ordered to do so.

In bestowing the Israel Prize upon him, the committee that presented the award cited Rabbi Druckman for his “important work in the field of religious-Zionist education.” The prize, which has been bestowed more than 600 times each year on Independence Day since 1953, has been presented to such luminaries as S.Y. Agnon and Martin Buber.

A former member of the Knesset from the National Religious Party, Rabbi Druckman, 79, was also recognized as “a unifying influence for all social groups.”

Steven Bayme, director of the Contemporary Jewish Life Department of the American Jewish Committee, said Rabbi Druckman is “one of the most effective and inspiring Judaic instructors anywhere in the State of Israel who has done important work with respect to conversion and setting up the Conversion Authority. And we should be saddened that a figure of such renown and esteem has such poor understanding of the dynamics of American Judaism and especially its religious pluralism.”

“It is a double affront given the fact that most American Jews identify with the non-Orthodox Judaism,” he added.

Bayme noted that Rabbi Druckman opposed the Sinai withdrawal as part of the peace treaty with Egypt in 1979 and “in that sense he has been an intellectual leader of the national religious right. They want to be very religious and they want a maximalist position on the territories and the peace process.”

Rabbi Richard Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, the congregational arm of the Reform movement, said that although Rabbi Druckman is “certainly entitled to his opinion … there is a major division in the Jewish world.”

“We don’t agree on who is a Jew and who is a rabbi,” he said. “But the State of Israel doesn’t decide that here. Here all the streams [of Judaism] work together and deeply respect one another in America. The Orthodox are part of the Jewish community. One thing we know here is that none of us has political power – and that levels the playing field because we all have the same Judaic role within our communities.”

In the interview, Rabbi Druckman was reminded that Reform and Conservative Jews recognize their spiritual leaders as rabbis. He said he found it unfortunate that Israel does not have a law that would spell out who should be called a rabbi.

“I think there should be [such] a law,” he said. “There is a law that says you cannot say something is kosher when it is not. … A rabbi means one who has the personality to be a rabbi, who has passed all the tests, who knows what a rabbi knows and who keeps in his own life what a rabbi is to do.”

Told that would not preclude a woman from being recognized as a rabbi, Rabbi Druckman smiled.

“You should see who the rabbis are through the generations. Women can do many jobs — many very important jobs — but not a rabbi, a rebbetzin.”

Rabbi Jacobs said that just last weekend the Reform movement ordained 13 rabbis, eight of them women. And he noted that last weekend was also the 40th anniversary of the ordination of the first woman Reform rabbi, Sally Priesand, and the 20th anniversary of the first woman rabbi ordained in Israel.

“In the Reform movement [rabbinical students] study for five years and along the way earn a master’s in Hebrew literature,” Rabbi Jacobs said. “It is rigorous. They are not only deeply committed but knowledgeable, and they function every day as wise and inspiring leaders.”

Rabbi Gerald Skolnik, president of the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly, said he was “not surprised that [Rabbi Druckman] has a problem” with recognition of non-Orthodox rabbis.

“It would require an unusual Orthodox rabbi to say to you that he was happy with that decision,” he said. “The decision is significant not so much because of what it says but because of what it represents. It is the first time that a government arm of the State of Israel has expressed any kind of formal recognition of the legitimacy of non-Orthodox rabbis.”

Asked how Rabbi Druckman’s opinions should be taken in light of the fact that he is considered among the more modern of the fervently Orthodox in Israel, Rabbi Skolnik replied: “Even progressive Orthodox rabbis in Israel are trying hard to push the envelop but hold a certain line. This decision I’m sure is seen by them as an unwelcome sign of bigger decisions yet to come down the road. I can only see it threatening to them.”

Seth Farber, a Modern Orthodox rabbi in Israel who is the founder and director of ITIM: The Jewish–Life Information Center, which helps Israelis deal with the legal intricacies of personal status such as divorce and conversion, said he was “not shocked” by Rabbi Druckman’s views.

“I have a lot of respect for Rabbi Druckman, but I think his comments highlight the fact that for Israel and its rabbinate to serve the historic role I believe it can it needs to engage in greater dialogue and have a greater appreciation of diaspora Jewry,” he said.

“I don’t think talking or understanding implies agreement,” Rabbi Farber said. “We are entitled to disagree but we have to do so out of a sense of respect and understanding of context, something that is dramatically lacking today.”

He added that the views Rabbi Druckman expressed are “not unprecedented but show how much more work needs to be done to bridge gaps between Israeli rabbinical leadership and the diaspora Jewish community.”

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, the chief rabbi of Efrat and chancellor and rosh yeshiva of Ohr Torah Stone, said he believes it is critically important that the religious establishment in Israel understand that it cannot exclude non-Orthodox Jews.

“Israel cannot be perceived as a country for Orthodox Jews alone,” he said Tuesday during a visit here. “It is legitimate for the religious establishment in Israel to say that a rabbi is a term used for synagogue leadership. It is not a term that has necessarily halachic [Jewish law] ramifications. A synagogue that meets and designates an individual as their rabbi has a right to do that, and I believe that particular office and title should be respected as such within Israel.”

Asked whether he agreed with Rabbi Druckman that Israel needed a law to define a rabbi just as it has a law to define kashrut, Rabbi Riskin replied: “Kashrut is different because it is an halachic expression. There should be a law defining kashrut and a law defining conversion and marriage. But I don’t think there should be a law defining a title of religious leadership.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.