Jews have long felt a special kinship with rocker Bruce Springsteen; his Jewish-sounding name, left-wing politics and his penchant for singing about the downtrodden have made Jewish mothers everywhere insist he’s one of the tribe.

The gravely voiced troubadour has been hailed as the Messiah of rock and roll, his concerts likened to religious revivals and his songs packed with biblical imagery. The banter among Springsteen’s E Street bandmates is downright heimishe — with Springsteen reportedly promising an audience a “rock and roll bar mitzvah” — and he’s been known on occasion to break out into “Hava Nagila.”

So it should perhaps come as no surprise that the rock icon has most recently been the subject of a course at Rutgers University in which Azzan Yadin-Israel, a professor of rabbinic literature, explored religious motifs in the famed Garden State native’s work.

The 20 students in the one-credit, fall semester seminar “Bruce Springsteen’s Theology” grappled with the interpretation of biblical stories in his songs, beginning with “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.’” Springsteen’s first album, released 41 years ago, to “Wrecking Ball,” released in 2012. Springsteen’s latest album, “High Hopes,” will be included in a future course, said Yadin-Israel.

The students pored over the songwriter’s lyrics, along with their theological sources, with all the intensity of Talmudic scholars. Not surprisingly, Yadin-Israel attests that the students were “incredibly engaged in the material.”

The seminar, offered in the fall for the first time, generated so much interest that Yadin-Israel plans to offer it again in the spring, and he is also working on a book based on the material in the course.

Joseph Duncan, a freshman from Holmdel, N.J., who plans to study engineering, said that as a longtime Springsteen fan and as a musician who plays in a band, he jumped at the chance to take the course. He learned that “Springsteen is able to take ideas many of us are familiar with and use them to preach his own spiritual message. … A common thread we saw in his works is that Springsteen depicts two realities: one of the idealistic religious and heavenly world, and one of what he seemed to find the true reality. In this reality Springsteen accepts a world driven by human emotion, by greed, and by the search for immediate satisfaction.” One example raised in class was “Thunder Road,” in which the biblical theme of salvation is equated to human actions, Duncan said. “Salvation here is seizing the moment, driving into the night (and presumably spending it) with someone you love. To put aside obstacles in the way of pure, raw love and just live, and in this way achieve salvation on Earth. I found his juxtaposition of the biblical world and the world around us within a song to be absolutely fascinating.”

Samantha Glass, a Rutgers freshman and aspiring English major from Hoboken who grew up listening to Springsteen because her father is a fan, signed up for the course because she knew it would make her feel at home.

“I grew up listening to the melodies and not hearing what he was saying.” In Yadin-Israel’s class, she began hearing those songs in a new way. For example, many of Springsteen’s songs seem to be about cars and love “and that’s it,” she said. But Yadin-Israel taught her to look beneath the surface into the deeper meaning of the text. He urged the class to examine the original Bible passages and pointed out similarities. “You have to read and understand the references to get a deeper understanding of the whole picture,” she said. “I was kind of surprised to learn that his lyrics were so intellectual and he thought so much about this [spirituality]. … The biblical references seem deep-seated.”

Yadin-Israel’s course, which garnered headlines in Rolling Stone and Time, was not the first time the gospel of The Boss has been dissected in the hallowed halls of academia: Princeton University has offered “Sociology from E Street: Bruce Springsteen’s America,” University of Rochester has offered a history course on the singer and Monmouth University has given several seminars about Springsteen.

And Yadin-Israel is certainly not the first to appreciate the biblical underpinnings of Springsteen’s lyrics. Rabbis, scholars and music fans have long talked about the spirituality in his songs. Some rabbis have even quoted the vocalist’s lyrics as a way of adding resonance to their own messages in sermons and lessons.

“Bruce explores many of the same themes that make religion such a deep part of the human spirit. His songs are about how to maintain faith and love and hope, even through times of suffering,” observed Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of Congregation Ansche Chesed in Manhattan. Even Springsteen’s concerts are religious experiences, he mused. “There is nothing like being with tens and thousands of other people in an arena, as Bruce sings ‘My City of Ruins.’ He’s chanting ‘I pray for the faith, Lord. I pray for the strength, Lord,’ and we all chant ‘Rise up!’ It’s a true religious moment.”

When Rabbi Dan Ornstein, spiritual leader of Congregation Ohav Shalom in Albany, and a longtime Springsteen fan, teaches the Cain and Abel story, he urges his students to examine Genesis Rabbah and other commentaries. “But of course we look at ‘Adam Raised A Cain.’ That song takes the story and gives it a unique interpretive twist. It’s a modern Springsteenian midrash, as are his references to the Promised Land, building a cross from the tree of evil and the tree of good and others. Whenever pop and general culture can draw students nearer to ancient biblical texts in a way that isn’t cheesy and forced, and doesn’t overdo the analogy between the two forms of literary expression, it is helpful.”

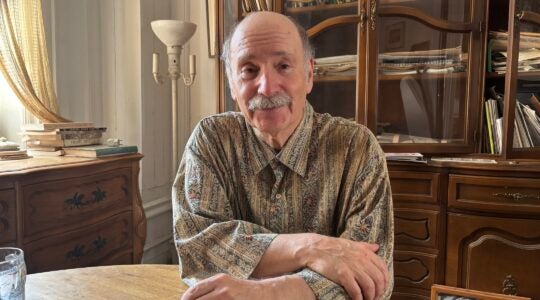

Probing the work of rock stars is not exactly common terrain for Yadin-Israel, an associate professor of Jewish studies and classics who has taught at Hebrew University, the University of Chicago, the Jewish Theological Seminary and the University of California. His latest book is “Scripture and Tradition: Rabbi Akiva and the Ironic Triumph of Midrash” (University of Pennsylvania Press 2014).

Yadin-Israel first became a Springsteen fan at age 12 — after his family moved from Israel to Cleveland — and he has followed the Boss’ career closely since then. He was moved to teach his latest course after publishing an article in The Jewish Review of Books about an Israeli band that uses rabbinic Hebrew in its lyrics. He started thinking about the band’s American equivalent, and Springsteen came to mind.

Yadin-Israel notes a progression in Springsteen’s understanding of biblical and religious matters. Early in the rocker’s career, he notes, redemption is understood in terms of cars, and the open road, whereas in more recent albums, it has to do with being engaged in the world and with the power of relationships. “There’s a theological evolution,” he said of Springsteen’s lyrics, adding that biblical references ring clear through all of them.

He also found that Springsteen, although he was raised in a Roman Catholic home and attended Catholic school, refers more often to themes in the Hebrew Bible than in the New Testament.

“On a literary level, Springsteen often recasts biblical figures and stories into the American landscape,” said Yadin-Israel, citing “Adam Raised a Cain” and “The Promised Land” as examples. “Adam Raised a Cain references the first biblical family and all its tribulations. There are a lot of statements he makes that can be understood in a more secular way but carry a kind of theological resonance. I’m referring to themes like the Promised Land or images of redemption. You can obviously use those terms more loosely. I think he purposely brings the cultural heritage into his songs.”

In “Thunder Road,” the protagonist tries to woo a woman in theological terms by advising her [don’t] “Waste your summer praying in vain for a savior to rise from these streets.” While she wants an unattainable ideal, he says the only redemption he can offer is in this world — what’s beneath his dirty hood, meaning his car. “He says he’s no hero, he can only offer her a worldly redemption. … It ends up being a fascinating theological debate,” says Yadin-Israel.

Springsteen gives several Bible stories a modern revision: “Rocky Ground” is about 40 days and 40 nights of rain, and “In the Belly of the Whale” offers a different perspective on the story of Jonah.

A Springsteen song can do just what a powerful midrash does, Yadin-Israel says: “He retells a story so you think about the original story in a new way.”

The biblical images are reflective of Springsteen’s Catholic upbringing as well as the nature of the blue-collar narratives that he explores in his various albums, said professor Ken Womack, who teaches English at Penn State University and is the author of “Bruce Springsteen, Cultural Studies, and the Runaway American Dream (Ashgate, 2008).”

Womack applauded Yadin-Israel’s initiative in teaching Springsteen and the Bible. “I have found through my own teachings that rock lyrics are useful inroads into a wide variety of disciplines, including religion, history, politics, sociology and literature.”

While Yadin-Israel said he anticipates a sustained commitment to this topic, he stressed that his primary area of interest will always remain rabbinic and classical literature. “When they talk about the classics, they aren’t referring to classic rock,” he quipped.

Deena Yellin is a newspaper reporter in New Jersey.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.