(JTA) — For most Jews, matzah season comes once a year. But for Jean-Claude Neymann, matzah, or “pain azyme” in French, is a defining family tradition.

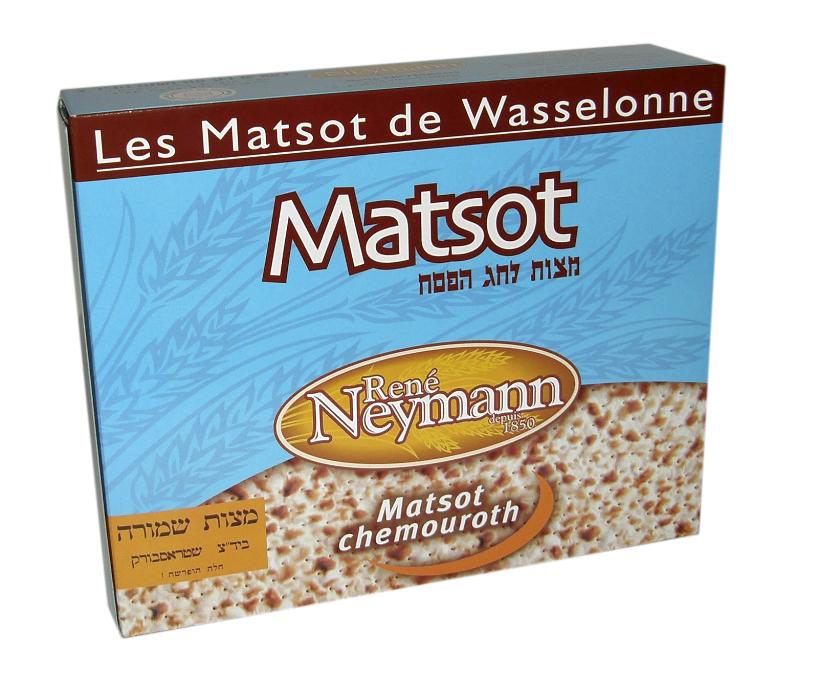

Neymann runs the oldest matzah bakery in France, located in the town of Wasselonne near the German border. The family company, Etablissements Rene Neymann, traces its matzah-making tradition to 1850.

“I’m the fifth generation of my family to bake matzah here in Wasselonne,” Neymann said.

Etablissements René Neymann is France’s oldest matzah bakery. (Courtesy of Etablissements Rene Neymann)

Walking along the steep, cobblestoned streets of Wasselonne, a city of nearly 6,000 people at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France, is like stepping into a Grimm’s fairy tale. Timbered facades look more German than French, a reminder that Alsace and Lorraine have been shunted back and forth between two countries that regularly warred with each other in the not-so- distant past.

Salomon Neymann, a peddler and the father of this unleavened-bread dynasty, set up his first bakery in nearby Odratzheim, where he began to bake Passover matzah for his family and the local Jewish community. His matzah became popular, and by 1870 he and his son Benoit moved the factory to larger quarters in Wasselonne, a market city with an industrial district that also had the advantage of being the site of a flour mill.

Between 1870 and 1919 the Neymann family manufactured regular and shmura matzah in their factory, but Benoit Neymann’s youngest son, Rene, had bigger ideas for the company. In 1919 he industrialized production, changed the company name to Etablissements Rene Neymann and in 1930 began to market the wonders of unleavened bread to the non-Jewish public. It was a hit and sales grew.

Jean-Claude Neymann runs the family matzah-making business. (Courtesy of Etablissements Rene Neymann)

After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, the bakery was shuttered and the Neymann family was forced into exile in southern France. Liberation came in November 1944 with the army of Gen. Phillipe Leclerc, and in 1948 Rene Neymann restarted the business.

The decades following World War II saw many changes in how people ate and shopped all over the world.

“Supermarkets started to replace traditional food markets, and eating a low-fat diet became fashionable,” Jean-Claude Neymann noted.

Robert Neymann, Rene’s son, seized the opportunities — he modernized and automated production, expanded the product lines and secured new distribution outlets.

With Robert Neymann at the helm, Etablissements Rene Neymann continued to extend its products and brands by manufacturing other types of matzah for different tastes and appetites: matzah made from rye and whole-wheat flours; bran matzah; spelt matzah; certified organic matzah. Even Neymann’s kosher for Passover matzah, under the supervision of the chief rabbi of Strasbourg, is made from an array of flours.

Jean-Claude, Robert’s son, took over the company in 1983.

“Regular matzah is still our biggest Passover item, but about 62 percent of our total manufacturing output is sold outside France,” he said. “We sell throughout Europe, to Morocco, South Africa, Japan and China. There’s a big market for crackers in those countries.”

Asked about the state of French Jewry and mounting concerns about anti-Semitism in the country, the proprietor of this storied French Jewish company was circumspect.

“I’m not afraid at this moment, but we can never know what people will do. Nobody imagined the Shoah could happen, but it did,” Neymann said. “We and our company are very well integrated into the life of Wasselonne and of France, but in people’s minds we are always the Jew.”

(Toni L. Kamins, a freelance writer in New York, is the author of “The Complete Jewish Guide to France” and the forthcoming ebook “The Complete Jewish Guide to Paris.”)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.