TOKYO (JTA) — Reading his Japanese-language newspaper over breakfast, Rabbi Mendy Sudakevich spotted an ad for a self-help DVD titled “Get rich like the Jews.”

“Almost anywhere else in the world, such an ad” — published in several widely read Japanese dailies — “would have been deemed anti-Semitic incitement,” noted Sudakevich, an Israel-born Chabad emissary who settled in Tokyo in 2000.

But in Japan, he and others said, it’s something akin to a compliment.

“[T]he takeaway is that Jews, and Israel by extension, should be emulated and embraced,” said Ben-Ami Shillony, a historian and lecturer on the Far East at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Indeed, Japan’s government — buoyed by the population’s generally positive bias toward Jews — has been actively seeking stronger economic ties with Israel. That’s especially true now that the nation’s decades-long dependence on Arab oil is waning due to America’s increased energy production and Japan’s decreased reliance on fossil fuels.

In 2014, trade between the two nations rose by 9.3 percent to $1.75 billion, according to Israel’s Ministry of Economy.

Warmer relations also yielded several recent joint memoranda on enhancing cooperation on research, trade, tourism and even security cooperation — an area that successive Japanese administrations regarded as taboo for fear that it would anger oil-rich Arab nations.

And in Japan, government policy has a substantially larger impact on private firms than in the West, Shillony said. This was evidenced in the decisions by nearly all the large Japanese carmakers not to enter the Israeli market until the 1990s, when the Arab oil boycott — a set of sanctions applied against nations that did business with Israel — began to loosen, he added.

Japan’s new certainty owes to the arrival in October of U.S.-produced shale oil, which is expected to put the United States ahead of Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest exporter of black gold. As production in the United States nears the projected rate of 11.6 million barrels a day by 2020, exports to Japan are expected to grow far beyond the current level of 300,000 barrels a month. At the same time, Japan is increasingly relying on green energy.

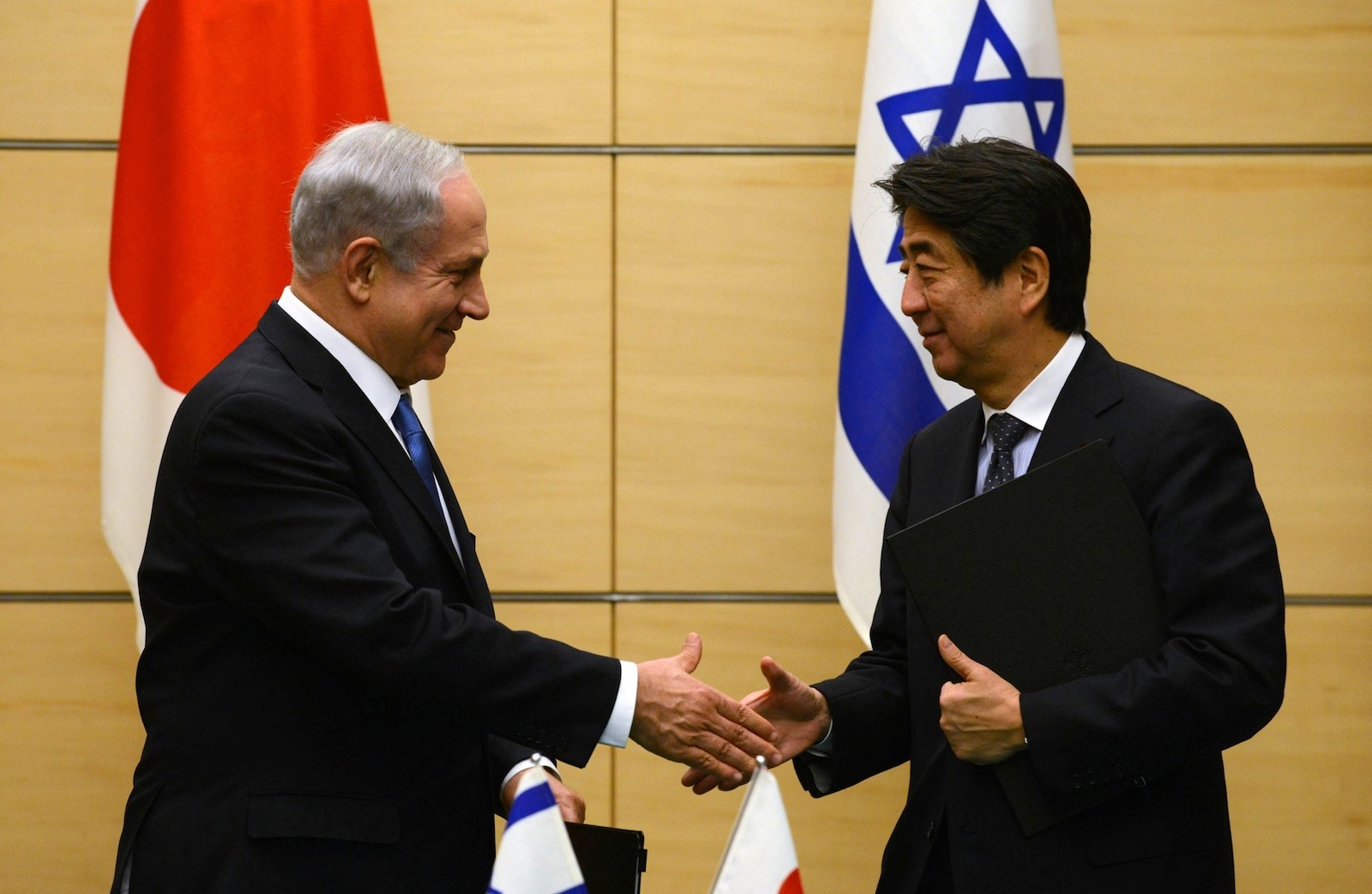

More evidence of warmer ties between Israel and Japan: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s official visit to Tokyo in May, where he and his wife, Sara, dined with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his wife, Akie, at Abe’s residence. Their meeting exceeded its allotted time — unusual for a state visit in Japan.

Abe, a center-right politician whose career and worldview in many respects align with that of Netanyahu, is heading to Israel later this month in the first state visit of its kind in nine years for a Japanese leader. Netanyahu’s predecessor, Ehud Olmert, visited Japan in 2008.

“I am determined, together with Prime Minister Netanyahu, to make further efforts to strengthen Japan-Israel relations, so that the potentials are fully materialized,” Abe told the media in Tokyo during his meeting with Netanyahu.

The feelings appear to be mutual.

On Sunday, Netanyahu’s Cabinet approved a series of measures aimed at boosting trade to the tune of several tens of millions of dollars. Israel will open an Economy Ministry office in Osaka and increase by 50 percent government grants for joint Israeli-Japanese research projects.

For Abe, strengthening ties with Israel is part of a larger vision for enhancing innovation and diversifying Japan’s highly centralized industries and markets in an attempt to reverse its declining economy and creeping inflation, according to Shillony.

In Abe’s Japan, the historian added, Israel is a particularly valuable partner because its unique expertise in defense and military technologies fits his plan for beefing up Japanese military capabilities against an increasingly defiant North Korea.

The Arab Spring of 2011 also changed Japan’s view of the region in Israel’s favor, according to Naoki Maruyama, a professor of history at Japan’s Meiji Gakuin University.

“With the region falling into chaos and internal strife, Israel stands out as the exception – and the place in which to invest,” he told JTA.

Abe’s economic doctrine of openness, which analysts often call “Abenomics,” already is changing the reality of doing business in Japan as a foreigner, according to Yoav Keidar, an Israeli businessman who has been working in Japan for the past 25 years.

“Once the main bottleneck for foreign firms, the government is now actively helping those firms overcome other blockages,” he said. “In Japanese terms, this is nothing short of a revolution.”

In Keidar’s case, the government fast-tracked permits for his telemedicine service — a vetting process that would have taken years in the past, he said.

Despite the dramatic increase in trade between the two nations, it’s still some 30 percent lower than Israel’s trade with South Korea, one of Japan’s main competitors.

That competition is another factor enhancing Israel’s appeal in Japan, according to Peleg Lewi, head of mission of Israel’s embassy in Tokyo.

“It did not escape Japanese industrialists and officials that Israel still has much stronger trade with some of Japan’s strongest competitors,” Lewi said. “At a time when giants like Samsung, Intel and Google are operating research centers in Israel, Japan is beginning to feel left out.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.