(JTA) — The story of Chiune Sugihara – the Japanese consul in Kovno, Lithuania, who disobeyed his government’s orders in 1940 and issued transit visas through Japan to thousands of Jews seeking to flee war-torn Europe — wasn’t widely known until 1985, when Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial authority, honored him as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

But I grew up hearing Sugihara’s story because he saved my father’s life. My father, the attorney Nathan Lewin, is a Sugihara survivor.

I also have a family connection to something that few others have known until very recently — the answer to a long unsolved mystery surrounding Sugihara’s rescue of an estimated 6,000 Jews.

Why did the Dutch consul in Kovno, Jan Zwartendijk, begin issuing the “Curaçao visas” – the Dutch endorsements that appeared to permit travel to the island of Curacao, Holland’s territory off South America upon which Sugihara relied when issuing visas? Why did Zwartendijk begin writing in Jewish passports that a visa was not needed to travel to Curaçao?

The answer: my late grandmother. Peppy Sternheim Lewin, the recipient of the first Curacao visa, is the “missing link” in the story.

READ: WWII diplomatic heroes honored for helping Jews escape Holocaust

My grandmother was a Dutch citizen, raised and educated in Amsterdam. After she married my grandfather, Dr. Isaac Lewin, she moved to his home country, Poland. When the Nazi army invaded Poland in September 1939, my grandmother’s parents and her brother were visiting her in Lodz, my father’s birthplace. My great-grandfather promptly flew back to Amsterdam to take care of his business. He later perished at Auschwitz.

My grandmother’s mother, Rachel Sternheim, and her brother, Leo Sternheim, were smuggled with my grandparents and my father, who was then 3 years old, over the border into Lithuania.

In Lithuania, my grandmother sought help from the Dutch diplomats because her mother and brother were Dutch citizens and because she had been a Dutch citizen prior to marrying my grandfather. She initially asked Zwartendijk, who was in Kovno, if he could issue her a visa to the Dutch East Indies, which included Java and Sumatra. He refused. So she wrote to the Dutch ambassador in Riga, L.P.J. de Decker. He also turned down her request for a visa to Java or Sumatra.

Refusing to be discouraged, my grandmother, who was then in Vilna – a short trip from Kovno — wrote to de Decker again and asked him whether there was any way he could possibly help her family because it included Dutch citizens. The ambassador replied that the Dutch West Indies, including Curacao and Surinam, were available destinations where no visa was needed. The governor of Curacao could authorize entry to anyone arriving there.

My grandmother again wrote to de Decker asking whether he could note the Curacao or Surinam exception in her still-valid Polish passport. She asked the envoy to omit the additional note that permission of the governor of Curacao was required. After all, she pointed out, she really did not plan to go to Curacao or Surinam.

“Send me your passport,”de Decker replied. So she did.

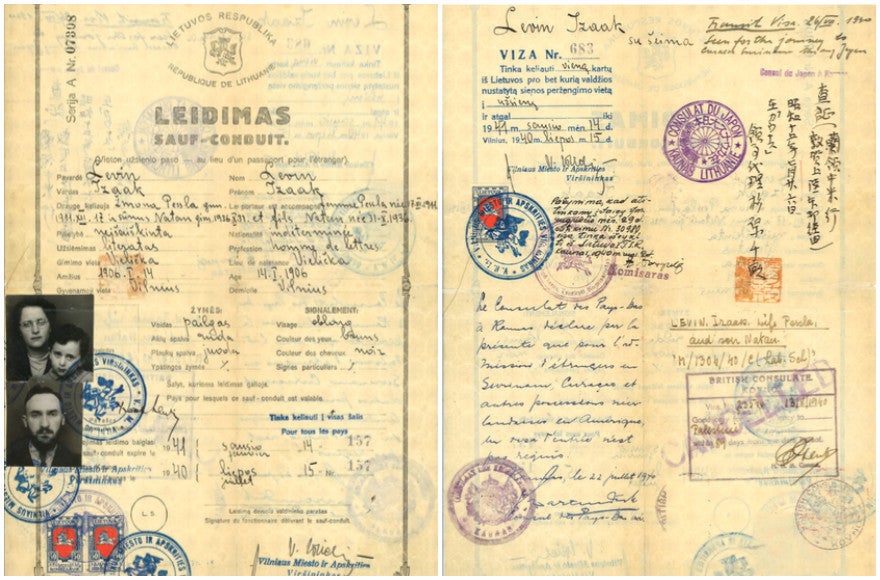

The endorsements of Chiune Sugihara and Jan Zwartendijk, the Japanese and Dutch consuls, respectively, in Kovno, Lithuania, appear on the Leidimas, or travel document, that allowed Isaac Lewin and his family to escape Lithuania in 1940. Nathan Lewin, now a prominent attorney, is the 4-year-old boy in the arms of his mother, Peppy Sternheim Lewin. (Courtesy of Alyza D. Lewin)

On July 11, 1940, de Decker wrote in her passport in French, “The Consulate of the Netherlands, Riga, hereby declares that for the admission into Surinam, Curacao, and other possessions of the Netherlands in the Americas, no entry visa is required.”

My grandmother then showed Zwartendijk what the Dutch ambassador had written in her passport and asked him to copy it onto my grandparents’ Leidimas – the temporary travel document they had been issued by the Latvian government after the existence of Poland was officially nullified by the Nazi invasion. On July 22, 1940, Zwartendijk agreed and wrote de Decker’s notation on my grandparents’ travel papers. That is how my grandparents and my father received the very first Curacao visa.

Relying on Zwartendijk’s notation, Sugihara agreed to give my grandparents (and my grandmother’s mother and brother, who were still Dutch citizens) transit visas through Japan on their purported trip to Curacao. Sugihara issued their visas on July 26, 1940. The Japanese consul kept a list of the names of the individuals to whom he issued visas. My great-grandmother, Rachel Sternheim, is No. 16 on the list; my grandfather, whose Leidimas included my grandmother and my father, is No. 17, and my great-uncle, Levi (Leo) Sternheim, received Sugihara’s 18th visa.

READ: Yukiko Sugihara, hero diplomat’s wife, dies

The number of visas Sugihara issued jumped exponentially on July 29, 1940, when hundreds of Jews who had escaped to Vilna learned of my grandmother’s successful effort. They crowded outside the Japanese consulate in Kovno (Kaunas in Lithuanian) hoping Sugihara would issue them a visa. Sugihara worked around the clock for a month, issuing 2,139 visas, including to whole families. These enabled the refugees to take the trans-Siberian railroad from Moscow to Vladivostok, and then travel by boat from Russia to Japan, supposedly en route to Curacao.

The story of Sugihara and his rescue is told in a feature film, “Persona Non Grata,” that had its premiere in October and is now making the rounds at Jewish film festivals across the country. It screened recently at the Washington Jewish Film Festival and was shown again in Washington, D.C., last month as part of CineMatsuri, the Japanese Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital. Although my grandmother’s role is one of the unsolved mysteries in the film, my father was asked to share his mother’s tale after a CineMatsuri screening.

There are perhaps 100,000 descendants of Sugihara survivors alive today. It is humbling to think that it was my grandmother’s initiative and perseverance that opened up this travel route to safety for so many.

(Alyza D. Lewin is a partner at the Washington, D.C., firm of Lewin & Lewin, LLP, where she practices law together with her father.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.