NEW YORK (JTA) — Rabba Ramie Smith of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale, an Orthodox congregation, says she doesn’t have time to protest the Orthodox Union decision banning its synagogues from hiring women clergy like herself.

This weekend, she’s busy organizing a Shabbat conference with Yachad, a group supporting Jews with disabilities. Then she has classes to plan, congregants to meet and a podcast to host.

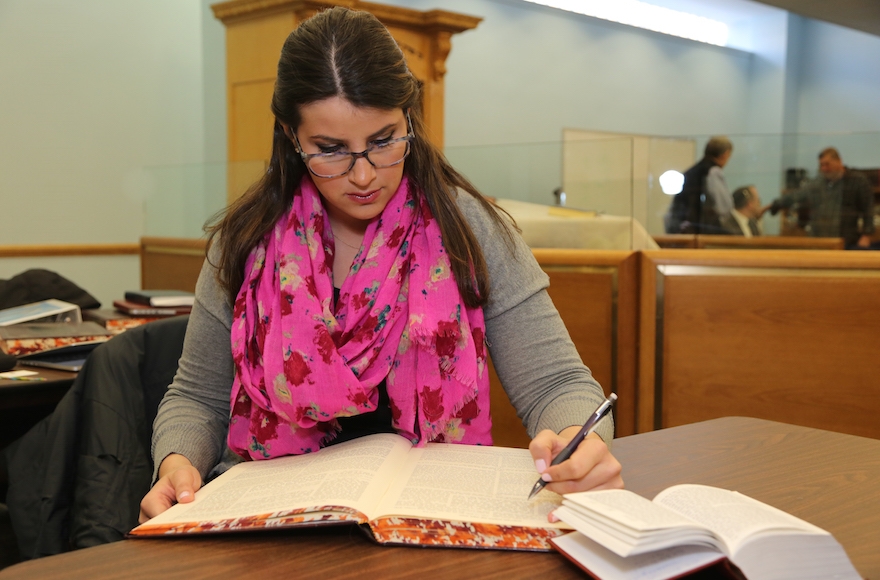

“The way I’m reacting is showing up to work and continuing to do my job,” Smith, who received ordination in 2016, told JTA on Friday. “It might make some people nervous, but the more we continue doing our jobs, having people see who we are and what we do, the work speaks for itself.”

Smith is one of 14 graduates of Yeshivat Maharat, which trains and ordains Orthodox women clergy members. The New York school was one of the main targets of a decision issued Thursday by the Orthodox Union, an umbrella Orthodox Jewish group, barring its member synagogues from hiring female clergy.

The decision, made by a committee of seven Orthodox rabbis, follows a 2015 decision by the Rabbinical Council of America — an umbrella group of Orthodox rabbis — that also barred women clergy. The O.U. decision says that while there is a place for women at synagogues to teach Torah, hold professional leadership positions and advise on certain Jewish legal matters, Jewish law prohibits women from filling a role akin to a pulpit rabbi.

“The formal structure of synagogue leadership should more closely reflect the halakhic ethos,” the decision read, using a Hebrew term for Jewish law. “For the reasons stated above we believe that a woman should not be appointed to serve in a clergy position.”

Five O.U. synagogues currently employ Yeshivat Maharat graduates — they all hold the title of “rabba” or “maharat” — and the ruling could discourage others from following suit. But graduates of the school said they were not surprised by the ruling and it would not affect their work.

Those who spoke to JTA said they have received overwhelmingly positive responses from their congregants.

“It’s jarring for the O.U. to be coming out and condemning this when so many communities are moving ahead with this,” said Maharat Ruth Friedman, who works at Ohev Sholom-The National Synagogue in Washington, D.C. “[In] our communities we have found that women’s leadership has become accepted much more quickly than we thought.”

Leah Sarna, due to receive ordination in 2018, opposes the O.U. decision but appreciates the Jewish legal process that guided it. (Courtesy of Sarna)

Yeshivat Maharat was founded in 2009 by Rabbi Avi Weiss, shortly after the liberal spiritual leader gave ordination to Sara Hurwitz, the first rabba. Hurwitz now serves as dean of the school, which has 28 students in addition to the 14 graduates, nine of whom are employed as clergy in synagogues.

The school, and Hurwitz personally, have faced backlash from Orthodox leaders. But Hurwitz says the O.U. decision hasn’t led her to question her commitment to Orthodoxy.

“I think that what we’re seeing is that Orthodox Judaism is a big tent,” she said. “I feel very strong and committed in my Orthodox practice, and so do my students, and they particularly want to serve in Orthodox communities and be part of Orthodox communities.”

The O.U. decision did emphasize that women could fill a range of non-clergy roles in the synagogue, from teaching to lay leadership. And it approved of women serving as “halachic advisers” who give Jewish legal advice to women on topics such as family purity and sexuality.

Rabbi Marc Dratch, executive vice president of the RCA, who supports the decision, said it shows the O.U. recognizes that women need to have a role in the synagogue.

“I think it was an important step for the O.U. in setting standards for congregations that are part of the umbrella,” he said. “What you have here is a nuanced statement that sets certain limits but encourages advancement in other areas.”

Leah Sarna, who is due to graduate from Yeshivat Maharat next year, said that while she disagrees with the decision, she understands the wariness that some Orthodox Jews have toward ordaining women as rabbis after thousands of years of a male-only rabbinate. Like them, she says, she appreciates the weight of tradition.

“Figuring out what Hashem wants from us is heavy and difficult work,” she said. “In our generation, this is our question, and this is what we’re trying to figure out.

“On one hand, it hurts. On the other hand, I’m not sure I would want it to be any other way.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.