NEW YORK (JTA) — When Megan Corbin was in school, she learned about the Holocaust as an optimistic story.

Her grade school, she said, “highlighted Anne Frank as the voice of hope, and that really wasn’t the reality.”

Now, as an eighth-grade language arts teacher outside of Seattle, she teaches about victims, perpetrators and civilians who were bystanders to the genocide or who rescued Jews. She asks her students — some of whom are refugees from dictatorships — to delve into questions of right and wrong that arose during the Holocaust. Next year, Corbin plans to devote more time to examining Jewish life in Europe before 1939, and the context that allowed the Holocaust to occur.

“To understand the Holocaust is not just to understand what happened during the years we talk about,” she said. “It’s to understand a much broader context of what happened before, and understand anti-Semitism and … how it was so ingrained into society. It didn’t just happen out of thin air.”

Corbin was one of 23 teachers who attended a seminar in New York this week on how to teach the Holocaust to public school students. The program aimed to expand the educators’ understanding beyond, as one teacher put it, “boxcars from Berlin to Birkenau,” and give students pedagogical tools to communicate the scope and depth of one of history’s worst humanitarian crimes.

“Many teachers, while they might try to teach the Holocaust, if they don’t know the history, they might have trouble teaching it well,” said Stanlee Stahl, executive vice president of the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, which supports families of non-Jewish families that rescued Holocaust victims and runs the seminar for teachers.

“Many teachers who teach Anne Frank give it a happy ending: ‘In spite of everything, I still believe that people really are good at heart,’” Stahl said, quoting Frank’s diary. “I think she would have rather lived. Rescue is part of the narrative, [but] it is a small part of the narrative. You should not go in and teach rescue and nothing else.”

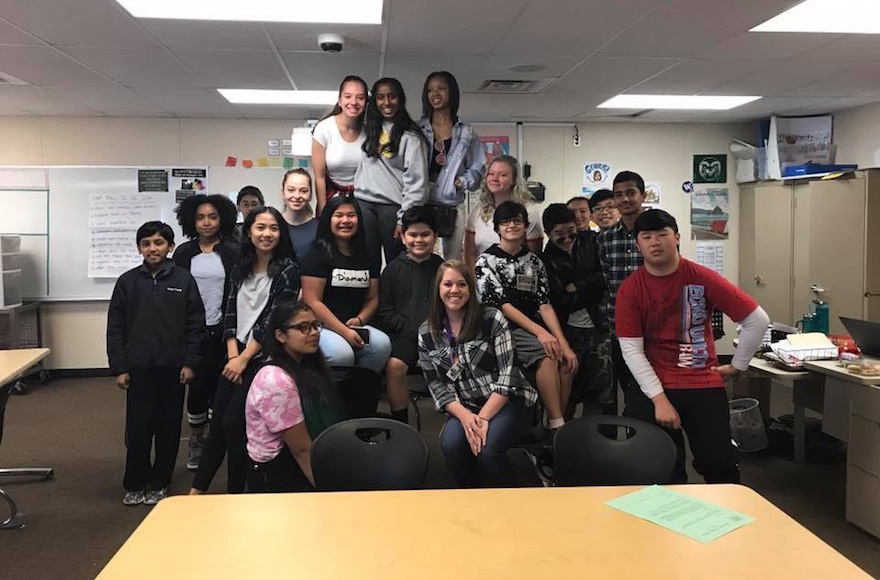

Megan Corbin, shown in front center with her Seattle-area language arts class, emphasizes the individual choices involved in the Holocaust. (Courtesy of Corbin)

Eight states now mandate genocide education beginning in either kindergarten or middle school, and running through high school. Legislators from 20 additional states have pledged to introduce legislation that would require public schools to teach about the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide and other genocides.

The seminar approached the Holocaust topic by topic, ranging from medical practices in the Third Reich to life in the ghettos to civilian collaborators in occupied countries. Much of the curriculum was devoted to providing context around the genocide itself. In one lecture Michael Steinlauf, director of the Gratz College Holocaust and Genocide Studies Program in Philadelphia, provided a detailed portrayal of Jewish life in Europe on the eve of the Holocaust, then spoke about life in the Nazi ghettos.

Steinlauf told JTA that his goal is to move students beyond a “Fiddler on the Roof” picture of European Jewry. While the image people have is usually of religious shtetls, he noted that European Jews were largely young and cosmopolitan, living mostly in cities.

“We’re not looking at a world that was primarily old Jews with payes,” he said, referring to the sidecurls sported by religious Jewish men. “They had camps, they had study groups, they had libraries, they went hiking together.”

After every lecture, the teachers gathered in groups to discuss the best pedagogical methods to communicate what they had just learned. After the Steinlauf lecture, teachers’ suggestions included having the class produce a newspaper about Jewish life in the ghettos and comparing the elements of daily life in the ghettos and Japanese internment camps in America.

But the teachers don’t bring everything they learn back to the classroom. Sometimes, said Ginni Stickney of Kansas City, Missouri, teaching the most gruesome details of the Holocaust to children can end up seeming disrespectful to the victims.

“I started to censor the images,” said Stickney, who teaches social studies to eighth-graders. “It was really important for us to see every victim as a person. When you’re showing these graphic images, you start to think, ‘If this was my family member, is this how I would want my family to be remembered?'”

The lessons of the Holocaust hit closer to home for teachers whose schools either have gangs — for whom violence is a daily part of life — or a large number of refugee children. Corbin teaches children from Myanmar, whose regime has been accused of genocide against stateless Rohingya Muslims, a connection she notes in class.

“I will call it out and I will say, ‘These things or similar experiences are so real for some of us in the room, for people in our community who live next door to us,’” she said. “This is a communal effort. It doesn’t just stay within the classroom.”

Stahl said the seminar doesn’t take political positions, but does note parallels between U.S. refugee policy in the 1930s and today. The goal, she said, is to make the lessons of the Holocaust relevant to all Americans.

“Teachers must be relevant to today, and by using the lessons from the past, they can teach the present into the future,” she said. “When you look at refugee policy, you see the doors of the world were closed to the Jews, and teachers can take it and extrapolate it to today.”

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.