BOSTON (JTA) — At 15, Elias Rosenfeld became a “Dreamer.”

At the time, the Venezuela native was attending Dr. Michael M. Krop Senior High School in Miami, where he had lived since he was 6 years old, when his Jewish family moved to South Florida from Caracas. His mother was a media executive and they traveled to the United States on an L1 visa, which allows specialized, managerial employees to work for the U.S. office of a parent company.

But tragedy struck the family: When Rosenfeld was in the fifth grade, his mother was diagnosed with kidney cancer. She died two years later.

In high school, Rosenfeld applied for a driver’s permit, only to find out that he lacked the required legal papers. He discovered that his mother’s death voided her visa. He and his older sister were undocumented.

“It was an embarrassing moment for me,” Rosenfeld recalled more than five years later.

Within five months, in June 2012, President Barack Obama signed an executive order, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, granting temporary, renewable legal status to young unauthorized immigrants who had been brought to America by their parents as children.

Known as DACA, the order opened up a world of opportunities for some 800,000 young people who were now able to apply for driver’s licenses, temporary work permits and college. “Dreamers” refers to a bipartisan bill, known as the Dream Act, that would have offered them a path to legal residency.

“It was the power of one order that can so directly change one’s life,” Rosenfeld said. “That launched me. I became an advocate.”

He launched United Student Immigrants, a nonprofit to assist undocumented students that has been credited with raising tens of thousands of dollars for help with scholarships and applications.

Rosenfeld, now a 20-year-old sophomore at Brandeis University on a full scholarship, spoke with JTA at a rally Tuesday outside of this city’s Faneuil Hall, just hours after President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced they would rescind DACA. The president gave Congress a six-month window to preserve the program through legislation. Or not.

The Boston protest was organized by the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition, where Rosenfeld is an intern. He shared his story with several hundred people at the quickly organized rally.

He explained that DACA enabled him to drive, buy his first car, and apply for internships, jobs and scholarships.

“Today’s news was cruel and devastating. Now is not the time of despair, however, but to put our energy towards effective action,” he said, urging the crowd to work for protective legislation at the federal and state levels. There are some 8,000 DACA residents in Massachusetts.

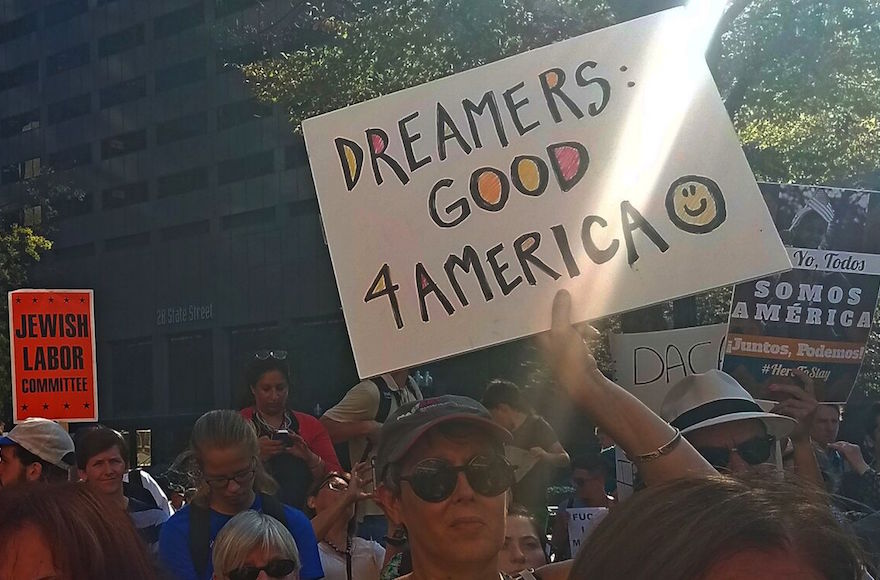

Several Jewish communal leaders attended the rally, including Jeremy Burton, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, and Jerry Rubin, president of Jewish Vocational Services. Representatives from the New England Jewish Labor Committee, which helped spread the word of the rally, held signs in the crowd.

Another Dreamer, Filipe Zamborlini, who came to the U.S. from Brazil when he was 12 and now works as a career coach at Jewish Vocational Services, also spoke.

“We’re going to mourn today,” Zamborlini, 28, told the assembly.

The New England Jewish Labor Committee helped spread the word about a rally in Boston in support of DACA, Sept. 5, 2017. (Marion Davis/Massachusetts Immigrant & Refugee Advocacy Coalition)

Rosenfeld said the Trump administration’s decision was disturbing and unsettling.

“There’s a high level of fear and anxiety in DACA communities,” he told JTA.

Rosenfeld recalls too well the sting and uncertainty of being undocumented.

“It means you can’t do everything your peers and your friends are doing. You feel American, but you are suffering these consequences from choices you didn’t make,” he said.

But he also sounded a note of optimism, pointing out that Trump called on Congress to act.

“We hope Congress follows their president’s word now and does the job of passing one of the many pieces of legislation” before them, Rosenfeld said.

He readily admits to feeling scared and anxious.

“But I’m also feeling empowered and motivated from seeing the outpouring of support,” locally and across the country, he said.

To DACA opponents, including Jewish supporters of Trump, Rosenfeld asks them to look at the facts and the stories of people like himself.

“I don’t think it aligns with our values, with Jewish values and the Jewish community,” he said of a policy that would essentially strip a generation of people raised here of official recognition.

Rosenfeld cited the activism of a group called Torah Trumps Hate, which opposes policies that it considers anathema to values contained in Jewish teachings.

Growing up, his family attended synagogue often and celebrated Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

Despite the hardships he faced following his mother’s death, Rosenfeld excelled in high school. He completed 13 Advanced Placement courses and ranked among the top 10 percent of his graduating class, according to a Miami-Dade County school bulletin. Rosenfeld was widely recognized as a student leader, receiving several awards and honors. During the presidential campaign, he volunteered for the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Many students who were undocumented live in constant fear, even after receiving temporary legal status under DACA, Rosenfeld said.

“There is fear behind the shadows,” he said. “We are always behind the shadows.”

Earlier in the day, before the president’s announcement, Brandeis President Ron Liebowitz sent a letter to Trump urging him not to undo DACA.

“Here at Brandeis University, we value our DACA students, who enrich our campus in many ways and are integral to our community,” the letter said. “Reversing DACA inflicts harsh punishment on the innocent. As a nation founded by immigrants, we can, should, and must do better.”

Rosenfeld was attracted to Brandeis both for its academics and its commitment to social justice. He is studying political science, sociology and law, with plans to continue his advocacy work on behalf of immigrants. He hopes one day to attend law school and work in politics or practice law.

With a full schedule of courses and volunteer work, Rosenfeld gets by without much sleep, he acknowledged with an easy laugh.

The Brandeis administration has been supportive, he said, and there is a meeting later this week on campus to discuss school policy on the issue.

Asked what America means to him, Rosenfeld does not hesitate.

“It means my country. It’s my home. There’s a connection. I want to contribute,” he said. “I just don’t think it’s valuable to want to kick out people that want to contribute to this country.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.