NEW YORK (JTA) — Just who is Bernie Bernstein, exactly?

Well, first things first: He — or, more accurately, it — is a disembodied voice that has become a supporting character in the brouhaha surrounding Roy Moore, the U.S. Senate candidate in Alabama who has been accused of sexual abuse by nine women.

Earlier this week, an unknown ally of Moore sent a fake robocall to households in Alabama saying that he was “Bernie Bernstein,” an ersatz reporter for the Washington Post. The recording offered a cash reward to women willing to make accusations against Moore. RoboBernie spoke in a generic but thick “regional” (read: Jewish) accent.

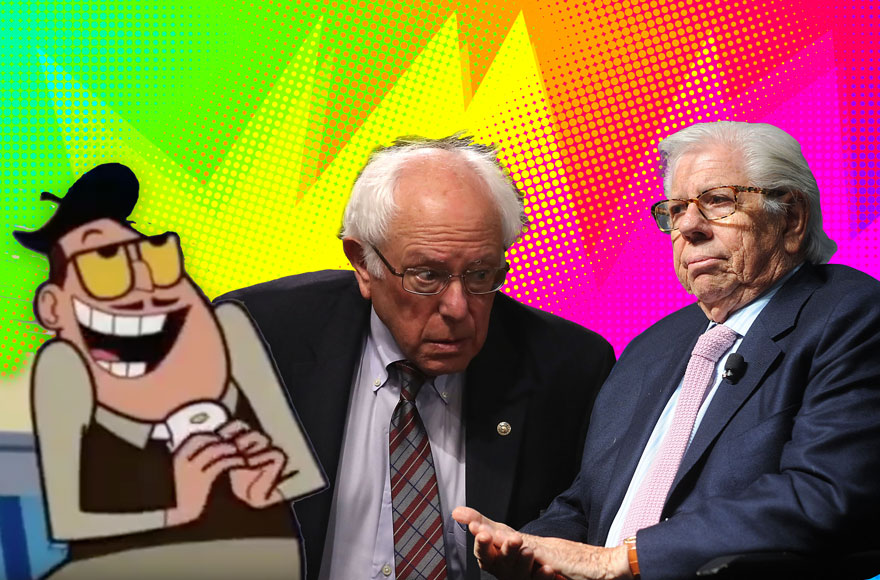

A bunch of people immediately noticed the robocall’s dog whistle. ADL National Director Jonathan Greenblatt called the recording “ugly” and “slanderous.” My JTA colleague Ron Kampeas pointed out that the name merged Bernie Sanders (a famous Brooklyn-accented Jew) with Carl Bernstein (a famous Washington Post Jew). One tweeter suggested that “Jewy McJew” might have been more straightforward.

Of course, unlike Jewy McJew, there are actual people named Bernie Bernstein. Just who are they, and how do they feel about this possible sullying of their name? Do the real-life Bernie Bernsteins have anything in common with their infamous robotic counterpart?

I decided to find out. On Wednesday, I called dozens of men named Bernie Bernstein — plus a few Bernie Bornsteins and Barney Bernsteins for good measure.

And if I had to summarize them all, I’d say this: Bernie Bernstein is a Jewish guy in his 80s — if he’s still alive, that is.

Like RoboBernie, he has an accent that includes dropping the r’s at the ends of his words. And like RoboBernie, he probably hails from Brooklyn, or maybe Manhattan, or possibly Westchester or New Jersey.

If you call him — and actually reach him — on a weekday afternoon, he’ll likely be friendly but wary. You’ll feel like you’ve interrupted him during his midday cup of mushroom barley soup. And he’ll firmly tell you that he definitely has nothing to do with Moore or that scandal in Alabama.

There are 108 people with the name Bernard Bernstein in the United States, according to WhitePages.com, and I called as many as I could in one afternoon. For two hours, with my old office phone wedged between my ear and shoulder, I went down the directory one by one seeking out the Bernie Bernsteins.

Most of them live in or near New York City, and were born in the years surrounding World War II. There are some near Philly and Baltimore, and a few in Northern Virginia and Cincinnati. I’m sure there are others but I stopped about halfway down the list. It was getting late, very few were answering the phone and there are only so many times I can say the phrase “This message is for Bernie Bernstein.” (Plus, none of them called me back.)

Before phoning Bernard Bernstein of Dollard-Des-Ormeaux, Quebec, I conferred with a French-speaking colleague on how best to pronounce “Bernarrr” — just in case my terrible French accent put him off. But Bernstein didn’t answer. I left a message. He didn’t return my call.

At least two of the Bernies were dead, and one had recently fallen ill. I offered my sincere apologies to their relatives.

Many of the numbers weren’t in service, and even more went to an automatic voicemail message. One guy in Massachusetts named Jonathan Bernstein told me I had dialed the right number but insisted that he had no relatives named Bernard.

I ended up interviewing three men. None of them had heard of the robocall, though they all knew about the Moore scandal. After describing the story, I had to carefully explain to each one that, yes, there was a robocall from a guy named “Bernie Bernstein” — and, no, I did not think they were that person. That Bernie Bernstein doesn’t exist, I explained — but, yes, I wanted to interview them because they did. Or something like that.

The first Bernie Bernstein I reached, of Manhattan, spoke with me as soft piano music played in the background, like he was a maitre d’ at a fancy Midtown restaurant. After letting me describe the premise of my call, he said he didn’t speak to the media and hung up.

The second Bernie Bernstein lived in the New York City area. He was in his 80s and told me that he was “annoyed,” though whether he was referring to my unexpected phone call or the sullying of his name, I couldn’t quite tell.

“I’m an old man,” he said. “I don’t want anybody bugging me. And I know there are numerous Bernie Bernsteins in the world.”

The third Bernie — of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn — was a little more effusive. I explained the nature of the Bernie Bernstein robocall.

“Well, I’m Bernie Bornstein,” he said.

He did know someone named Bernie Bernstein, a record distributor who lived around him in the ’60s.

“But I don’t know if he’s still alive,” Bornstein said.

He paused before amending: “Yeah, he would be dead.”

There are others, of course. One Bernie Bernstein, who looks a couple generations younger than his namesakes, works in tech and has 154 followers on Twitter, but hasn’t posted in more than a year.

As for famous Bernie Bernsteins, a New York Times obituary of Feb. 7, 1990, told of the death, at 81, of a lawyer and Treasury Department official who served as a financial adviser to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower in World War II. He later shows up in JTA’s archive as “chief of the B’nai B’rith liaison office with the United Nations” and “legal counsel of the American Jewish Conference.” Among his papers at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum are some documenting “loyalty charges leveled against him and his wife during the 1940s and 1950s.”

Bernard Bernstein is also the name of a well-known jeweler, silversmith and teacher who was born in 1928 and known for his high-end Judaica.

There’s at least one other fictional Bernie Bernstein: A villain by that name appears in an episode of “The Powerpuff Girls” from 2001. This Bernie Bernstein is a sleazy movie producer who turns out to be a money-grubbing con artist. The character manages to combine two anti-Semitic tropes into a single episode of a children’s cartoon — no small feat.

Unlike the cartoon version, the real-life Bernies I spoke to weren’t sure the robocall was anti-Semitic in nature. The second, the self-described “old man,” said he was “disturbed” that the caller used a Jewish name.

Bornstein, meanwhile, plumbed the depths of his personal history.

“Down South, they don’t like Jewish people,” he said. “I was in the Army in South Carolina and one guy said to me, ‘Where’s your tail, and where’s your horns?’”

But that was half a century ago, he acknowledged.

Whether Bernstein or Bornstein, all the men I talked with agreed on one thing: “This,” the second Bernie said, “is the most bizarre story I’ve ever heard.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.