(JTA) — In recent days, the ongoing controversy over the role played by Poles during the Holocaust has intensified dramatically, with Poland withdrawing from a planned conference in Israel that also was to include Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia following unfortunate accusations by Israeli government officials.

While tensions are running high, a recently rediscovered letter sent to a Jew in 1943 Nazi-occupied Poland reinforces why we must eschew what World Jewish Congress President Ronald Lauder has termed “obnoxious and offensive stereotypes that have caused so much pain and suffering on both sides over the years,” and instead focus on the unsung individuals who undertook daring and often improbable rescue initiatives during the Holocaust.

I received a copy of the letter on Jan. 30, three days after International Holocaust Remembrance Day. It had been found in a Holocaust-era archive in Israel, and Markus Blechner, the honorary consul of Poland in Zurich, had kindly emailed it to me.

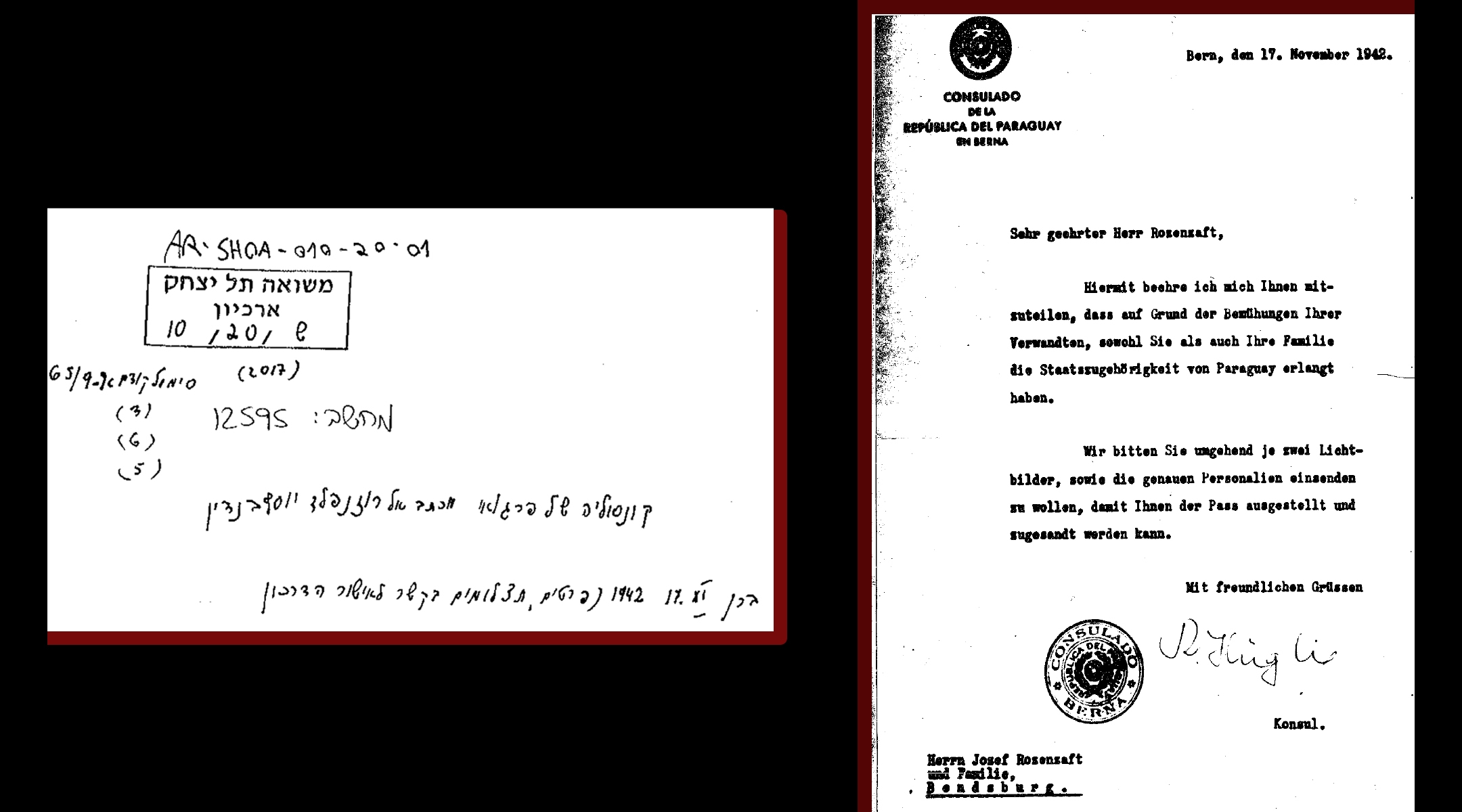

“Dear Mr. Rozenzaft,” the letter reads, “I am herewith honored to inform you that as the result of efforts by your relatives, you as well as your family have acquired Paraguayan nationality (Staatszugehőrigkeit).”

In Nazi-occupied Europe, for a Jew to be in possession of a genuine or forged passport, visa or other document indicating that the holder was a citizen or national of a neutral country, or had the necessary papers to travel to such a country, could mean the stark difference between survival and a more-than-likely death sentence. However tenuous, such documentation had the potential of providing a Jew with some seemingly official legitimacy that might persuade a German bureaucrat to allow the Jew in question safe passage, or at least spare him or her from deportation to a death camp.

The letter was dated Nov. 17, 1942, and was written on the letterhead of the Consulate of the Republic of Paraguay in Bern, Switzerland. It bore both the signature of that country’s honorary consul and the consulate’s seal, and was addressed to my father, Josef Rozenzaft (the Polish spelling of our family name became Rosensaft after the war) in Bendsburg, the Germanized name of his hometown of Będzin in a southern part of Poland that had been annexed by the Third Reich in 1939.

Josef Rosensaft was my father, but this was the first time I had seen this letter. I am quite certain that my father never received it or even knew of its existence.

According to a ledger page I received from Jakub Kumoch, the current Polish ambassador to Switzerland, the letter was sent to my father on May 25, 1943. By then, the Final Solution was in full force. On June 22 of that year, less than a month after the letter supposedly left Bern, my father was deported for the first time to Auschwitz. He escaped before he got there by diving from the moving train into the Vistula River, and although he was struck by three German bullets – one grazed his forehead, another hit his arm and a third remained lodged in his leg the rest of his life – my father managed to return to the Będzin Ghetto, only to be deported to Auschwitz again in late August 1943. He survived many months at Auschwitz followed by several other Nazi concentration camps, and was liberated by British troops at Bergen-Belsen in Germany on April 15, 1945.

The very fact that someone made an attempt, however futile, to rescue my father and his family at the height of the Holocaust is a stark reminder of the fact that heroic individuals in different parts of Europe were desperately trying as best they could to frustrate the Hitlerite plan to annihilate European Jewry.

We have long known that tens of thousands of Jews were able to escape almost certain death thanks to the protective documents issued by diplomats from Sweden, Switzerland, Japan, Portugal, Brazil, China, Peru and other countries, often in defiance of their respective governments’ explicit orders.

Less well known, but no less deserving of lasting recognition and gratitude, is the clandestine initiative undertaken by a small group of Polish diplomats and Jewish activists in Switzerland.

Known as the Bernese Group, they forged Latin American passports and issued certifications of Paraguayan nationality for Jews in Poland and elsewhere facing almost certain annihilation. This endeavor was largely funded by the Geneva office of the World Jewish Congress through an organization called RELICO (the Relief Committee for the War-Stricken Jewish Population) headed by Dr. Abraham Silberschein, a former member of the Polish Parliament.

Konstanty Rokicki, a Polish consul, together with Julius Kuhl, a Jewish attache at the legation, bribed Latin American diplomats – in particular the above mentioned honorary consul of Paraguay – to obtain blank passports, which Rokicki then proceeded to forge manually. Rokicki also obtained blank signed letters from the honorary consul, such as the one sent to my father, stating that the recipient was a Paraguayan national.

Aleksander Lados, the Polish ambassador to Switzerland, oversaw both the operation and its cover-up, provided his fellow conspirators with diplomatic support and convinced the Swiss authorities to turn a blind eye to the group’s efforts. Helped by Jews in Switzerland with contacts in various ghettos of Poland, including Alfred Schwartzbaum, a refugee from my father’s hometown living in Lausanne who gave the diplomats my father’s name, the Bernese Group compiled lists of Jews for whom the forged passports or nationality letters could be created, and then arranged for the fake documents to be smuggled to the Warsaw Ghetto, Będzin and other locations in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The Bernese Group also provided passports to Dutch, Slovakian, Hungarian and German Jews. One such false passport, in the name of Jan Lemberg, enabled a future French prime minister, Pierre Mendès-France, to travel from Geneva through occupied France to Portugal and from there to London.

While most of the thousands of passports and letters of nationality manufactured by the Bernese Group either did not reach their intended destination or proved to be of little if any avail, hundreds of the documents were in fact honored or resulted in their holders receiving preferential treatment from the German authorities that enabled them to survive.

We cannot and must not overlook those Poles who betrayed their Jewish neighbors to the Germans, who killed Jews or who profiteered from the ghettoization and deportation of Polish Jewry. But at a time when historians and politicians debate what did and what did not happen in Poland during the years of the Holocaust, it is equally important for us to publicly acknowledge and honor those Poles, like the diplomats in Bern, who altruistically sought to save Jewish lives.

The current Polish ambassador to Switzerland, Kumoch, dedicates himself to integrating the accomplishments of the Bernese Group into the historiography of the Holocaust. He emphasized in an interview on Polish radio in 2018 that the Bernese Group was “a Polish-Jewish operation,” and that those who categorize it as only Polish or only Jewish “falsify history.”

Kumoch is indeed an admirable and worthy successor to Ambassador Lados and the other members of the Bernese Group who did not know my father but nonetheless tried to throw him a lifeline in what was truly humankind’s darkest hour.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.