(JTA) — On the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, a public high school in the Austrian capital corrected its own historical record.

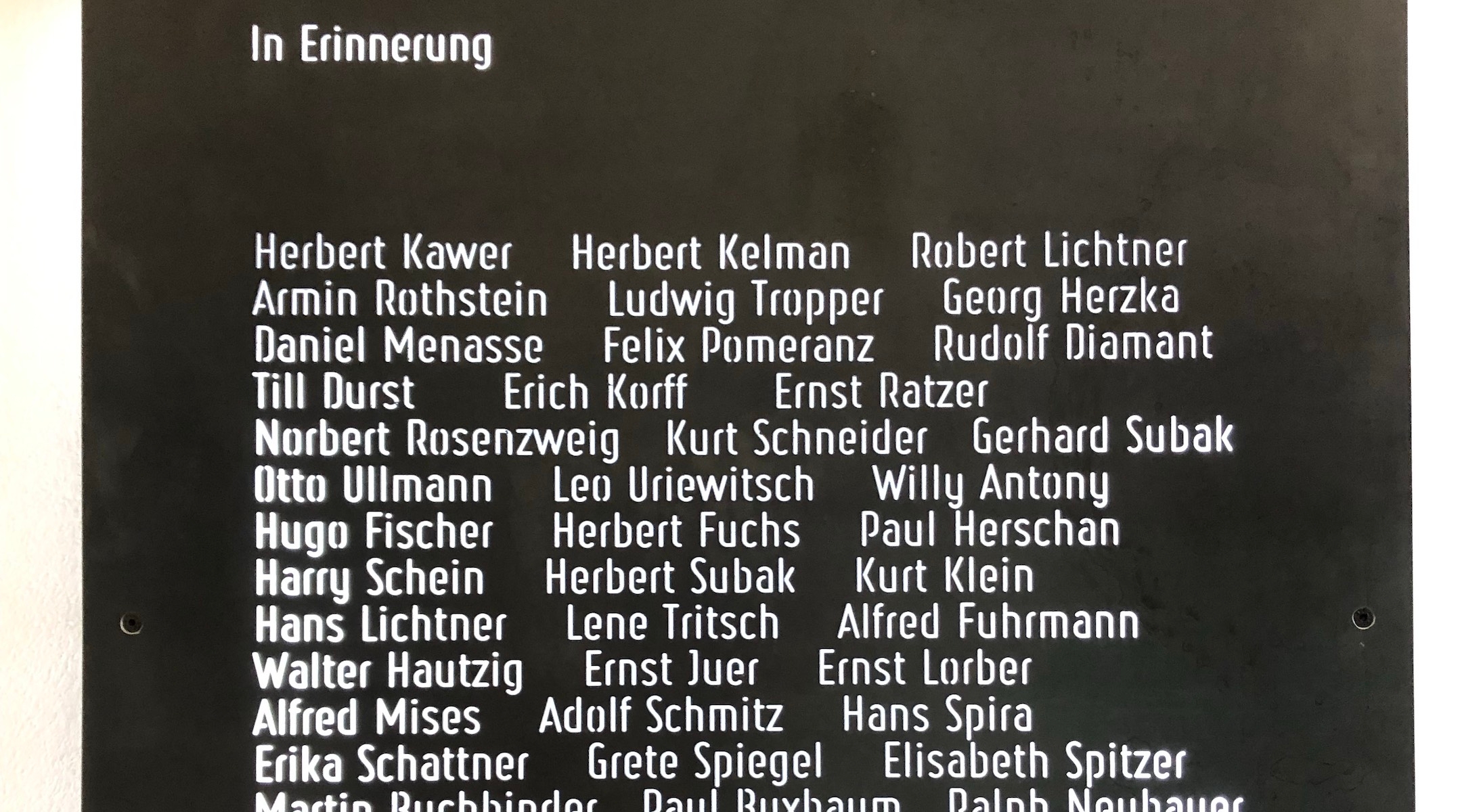

Along with a memorial to World War II soldiers, the Gymnasium Kundmanngasse now also has a plaque with the names of all 50 Jewish students expelled from the Vienna school exactly 81 years ago. And the life stories of these pupils – some tragically cut short – are contained in a book written by teenagers now attending the school.

The dedication of the new memorial on April 25 came just as a new survey reveals a disheartening lack of knowledge about the Holocaust among adults in Austria. But the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Study also found a profound commitment to Holocaust education among Austrians, particularly among younger adults.

The study was commissioned by the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany and released May 2, Holocaust Remembrance Day, or Yom Hashoah.

Among the survey findings:

- 58 percent of Austrians do not know that 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust;

- 36 percent of respondents said they believed people still talk too much about the Holocaust;

- 28 percent said they believed that many Austrians acted heroically to save Jews, when in fact only 109 are recognized as rescuers by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial and archive.

On the positive side, 82 percent of respondents – and 87 percent of younger ones — said they believe that Holocaust education is important.

Data was collected from a randomly selected, demographically representative sample of 1,000 Austrian adults. It was analyzed by Schoen Consulting in New York.

A plaque, reading “In Memory,” at the Gymnasium Kundmanngasse commemorates 50 Jewish students expelled from the Vienna school exactly 81 years ago. (Gymnasium Kundmanngasse)

“On one hand, there are some troubling, problematic results,” Greg Schneider, the executive vice president of the Claims Conference, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “On the other hand, there is a recognition of the importance of learning about the Holocaust, which is very hopeful. It gives us a road map to ensure that the Shoah is taught in schools and given the proper context and support.”

The first duty of Holocaust education is “to honor the memory of those who were killed,” he said.

Oskar Deutsch, president of the Jewish Communities in Austria and Vienna, said in a statement, “The lack of knowledge among many Austrians revealed through this study sets a mission for not only teachers and politicians but all society. A sincere handling of antisemitic incidents today and misrepresentations of the Shoah is crucial.”

Compared to Germany, Austria was notoriously late in confronting its role in the persecution and genocide of its Jewish population. What might be called willful ignorance changed dramatically in the mid-1980s, when the Nazi past of then-chancellor candidate Kurt Waldheim was put on the table. He was elected despite the questions raised about his role.

In 2000, Austria’s Ministry of Education, Science and Research established a Holocaust education program – errinern.at, or “remembrance.at” – that oversees educational projects on the national and state level with help from other foundations. Its programs reach thousands of teachers and students each year.

Today there is a “broad societal consensus that Austria has a responsibility and a share in this history,” said Martina Maschke, chair of errinern.at, in an interview before the Claims Conference survey’s release. Since the Holocaust is a paradigm for genocides, “there will never be enough Holocaust education.”

That’s especially clear today, Maschke said, with the rise of the right wing and an increase in anti-Semitism from migrants “socialized in Muslim countries.”

“Of course, the administration is always one step behind the political factum, and this is something that makes me rather sad,” she said. “But I think that this goes for every society.”

In fact, Schneider said, the results of the survey in Austria are similar to those in recent surveys that the Claims Conference commissioned in the United States (April 2018) and Canada (January 2019). He said they share an “appalling lack of knowledge, and a tremendous commitment to the importance of Holocaust education.”

It was just such a commitment that inspired Katharina Fersterer, a history and English teacher at the Gymnasium Kundmanngasse.

Fersterer, 29, had long been interested in Holocaust history. Austria’s Ministry of Education sent her to a summer program at Yad Vashem two years ago, and she returned determined to add to her school’s historical record in time for its 150th anniversary this year.

“My principal said, ‘Yes, let’s do this,’” Fersterer recalled.

Her students found the names of 50 Jewish students forced to leave the school in April 1938, shortly after Germany annexed Austria.

“But we didn’t stop at that. We wanted to know what happened to them,” Fersterer said.

It turned out that most of the former Jewish students had been able to escape Nazi-occupied Austria via the Kinderstransport, a rescue operation that brought Jewish children from Germany, Austria and then-Czechoslovakia to England in 1938-39.

“But some were also killed in concentration camps,” she said.

The students started looking for descendants of the survivors. Ultimately the project, including art and video, involved teachers and students in other departments.

That’s when Elia Ben-Ari of Arlington, Virginia, received her first Facebook message from Samuel, a 17-year-old senior in Fersterer’s class who asked that his last name not be used.

His message came “out of the blue,” Ben-Ari said in a recent interview, “from somebody who said he was a student doing a project about my father. My first reaction was, ‘Who is this person? How do I know this is legitimate?’”

Samuel had chosen to write about two students – Ernst Ratzer, who did not survive the Holocaust, and Martin Buchbinder, who was sent to safety in England in 1939 and later changed his name to Moshe Ben Ari. After living in Israel, he eventually settled on suburban New York’s Long Island with his family. He died in 2011.

Moshe Ben Ari was one of the children expelled from the Vienna school. A current student at the school has been researching his life story. (Courtesy of Elia Ben-Ari)

Luckily, Moshe Ben Ari had written an autobiography – “My Pre-American History” – that gave Samuel enough information to go on. But it was just the beginning of his research.

“It was really a surprise to actually find a relative, and when it turned out that she was actually his daughter, I was obviously very excited and happy,” Samuel said.

On April 25, the school held a ceremony and dedication of a plaque remembering the 50 former Jewish students.

“We now have a kind of book with all their life stories,” Fersterer said.

That book sits alongside Moshe Ben Ari’s autobiography for anyone to read, in the room with the plaque, she said.

“There is no question that there are teachers who manage to succeed, who are doing a lot,” said Richelle Bud Caplan, director of the European Department at Yad Vashem’s International School for Holocaust Studies and a member of the Claims Conference survey task force.

“It doesn’t have to do with funding. It has to do with support from the school administration to create a local momentum, a learning community,” she said. “We very much want people to focus on individual stories, so youngsters can connect,” and understand that “the majority of those who lived during this complex and difficult period did not survive.”

“Our school has a memorial remembering the fallen soldiers of World War II, but it didn’t have one memorial for the Jewish students,” said Samuel, who walks the same halls and climbs the same stairs that they did.

“I can imagine it was terrible,” he said. On the students’ last day, “mobs formed at the entrance of our school, where a few hardcore teachers and students were spitting and shouting names. So it was not a very kind goodbye, as you can imagine.”

As for Ben-Ari, she regrets that she could not attend the dedication ceremony. But “I think my father would have been gratified to know that somebody read his history and cared about it.”