WASHINGTON (JTA) — Shortly after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, the leadership of the South African Jewish community requested a meeting with President Cyril Ramaphosa to discuss rising antisemitism.

The meeting took place in December, and the course it took surprised the South African Jewish Board of Deputies: Instead of discussing the safety concerns of his Jewish constituents, the board’s leader said, Ramaphosa spent most of the meeting attacking Israel, which he accused of committing genocide. He later cited the meeting when South Africa charged Israel with genocide at the International Court of Justice.

“It was a complete betrayal of the community,” Wendy Kahn, the Board of Deputies’ director, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an interview this week.

Ramaphosa had scheduled the meeting for Dec. 13, after the launch of the country’s summer holidays, so a number of the seven Jewish officials who attended had to cut into summer travel plans to make the meeting in the capital city of Pretoria.

The inconvenience seemed worth it, Kahn said. Antisemitism had spiked in South Africa and the parliament’s overwhelming vote to cut diplomatic ties to Israel and shutter its embassy was creating problems for the South Africans with family in Israel.

Yet instead of focusing on those issues, according to Ramaphosa’s office, the South African president used the meeting to accuse Israel of genocide. His statement following the meeting does mention his government’s “denunciation of anti-Semitic behavior towards Jewish people in South Africa, including the boycott of Jewish owned businesses, and Islamophobia.”

But most of the statement concerns South Africa’s criticism of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. It says Ramaphosa explained that his government “condemns the genocide that is being inflicted against the people of Palestine, including women and children, through collective punishment and ongoing bombardment of Gaza.”

Kahn said the Jewish leaders were taken aback by the turn the meeting took.

“We told him about antisemitism, we told him about the boycotts,” she said. But in the president’s response, Kahn recalled, “He suddenly comes up with all this information about genocide, the genocide that Israel is committing, because, you know, he had to tell us that there was this genocide.”

Why Ramaphosa felt the need to bring up the genocide accusation wasn’t clear to Kahn’s organization until weeks later, when South Africa submitted its complaint to the International Court of Justice charging Israel with genocide.

In the document’s 13th section where South Africa was asked to show that “Israel has been made fully aware of the grave concerns expressed by the international community… and by South Africa in particular,” it listed the meeting with the Jewish Board of Deputies as evidence.

The community interpreted that to mean that Ramaphosa effectively considered them agents of Israel, Kahn said.

“A meeting that was called to discuss antisemitism became actually a meeting where antisemitism was committed,” she said this week. “We were absolutely shattered to see that the South African Jewish Board of Deputies was included, was cited in the case at the ICJ.”

Ramaphosa’s office did not return a request for comment or an answer to the question whether he views South Africa’s Jews as Israeli agents. Some South African politicians have explicitly argued that case, such as a Cape Town lawmaker who unsuccessfully called for a Jewish high school to be penalized last year because one in five graduates joins the Israeli army.

“The SAJBD made it clear that we are not the representatives of the state of Israel nor go-betweens of the two countries,” the Board of Deputies said when it realized the meeting was being instrumentalized as part of the genocide charge. “We are South African citizens like any other, with valid concerns about our human rights as citizens of this country.”

The encounter was of a piece with the hostility that the community has endured from sectors of the South African political establishment, Kahn said. She noted how Justice Minister Ronald Lamola, appearing at The Hague in January during the genocide hearings, was asked about antisemitism in his country.

“In South Africa, we have got a number of Jewish people doing business, living with us, and they also attend their churches in peace,” Lamola said.

The Board of Deputies had given the ministry a report on antisemitism, Kahn said.

“You’re the one who should be protecting South African Jews against hate,” she said of Lamola. “And you’re saying there’s no there’s no antisemitism. You haven’t even bothered to find out what the actual actual information is.” There have been at least eight cases involving antisemitic hate allegations brought to South African courts since Oct. 7, she said.

South Africa has long been critical of Israel, and in January, the Jewish captain of its under-19 cricket team was removed from his post due to anti-Israel protests against him. A 2019 report by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research found that of the country’s approximately 52,000 Jews, more than 40% “say that they have considered leaving South Africa permanently in the past year.”

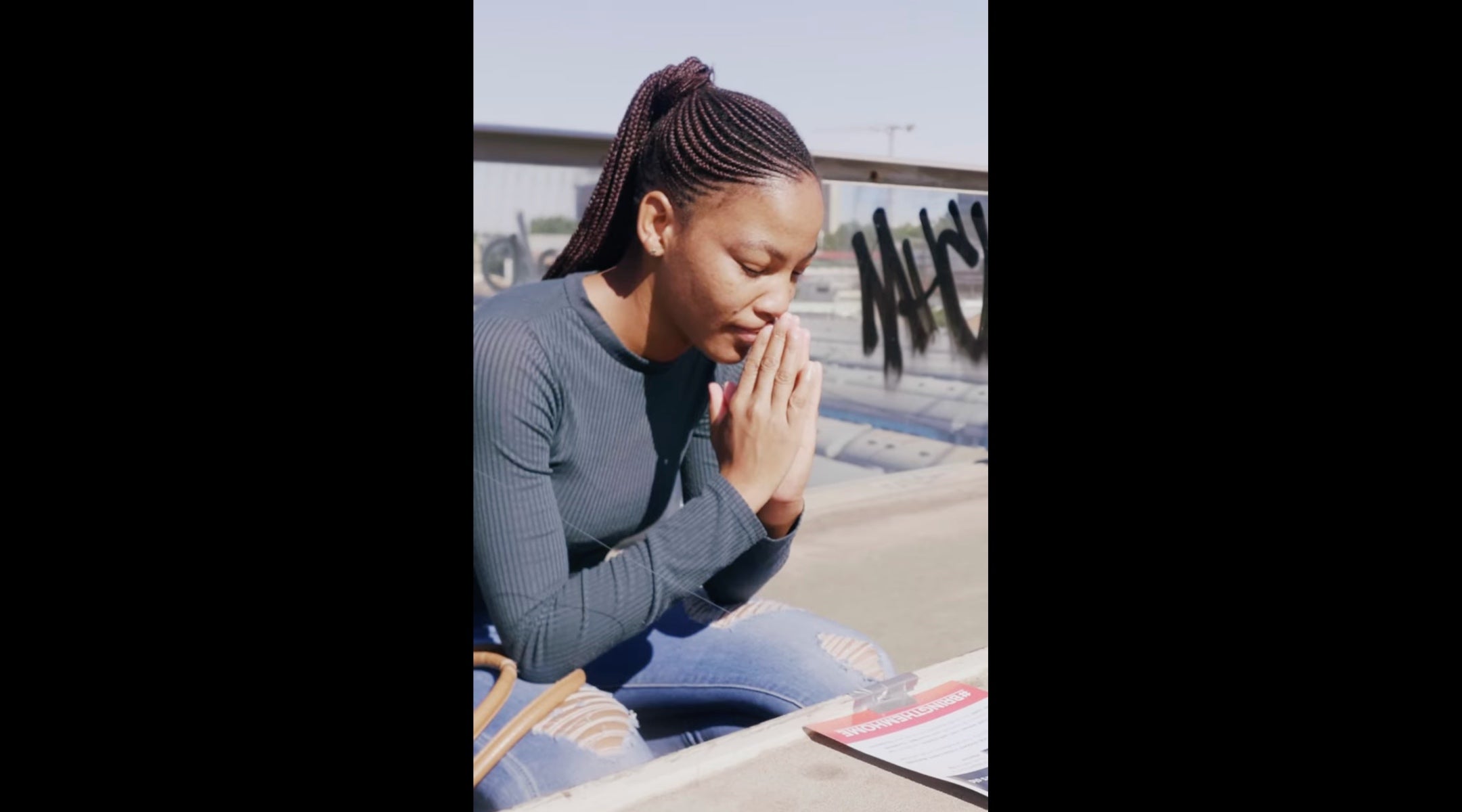

A woman prays over a missing poster for a hostage abducted by Hamas terrorists, on the Nelson Mandela Bridge in Johannesburg, Oct. 27, 2023. (South African Jewish Board of Deputies/YouTube)

Kahn, who was in Washington this week on a trip organized by the World Jewish Congress, emphasized that antisemitism was not pervasive in the country. She said the community has friendly ties to parties in opposition to Ramaphosa’s African National Congress, as well as with Christian churches with memberships numbering in the tens of millions. It also has a good relationship with law enforcement.

She has heard that the number of Jews seeking to leave the country has increased but said that has more to do with political and economic instability. The reports of increased antisemitism may be a factor, but not the only one, in a desire to leave, she added.

She also said Jews are not hiding visible symbols of their identity.

“We’ve got a jeweler in our community, he’s got a jewelry shop in one of the big shopping malls near the Jewish community” in Johannesburg, she said. “And he tells the story that he cannot keep up with the demand for Magen Davids. They are really flying out of the shop.”

The most poignant representation of grassroots sympathy for Israel, she said, came on Oct. 27. The community, without first seeking police permission, taped posters of hostages taken by Hamas along the ramparts of the Nelson Mandela Bridge. They also placed 221 red balloons along the bridge, one for each of the people known at the time to be held captive.

Kahn said the community intended to keep the posters in place for an hour, wanting to avoid confrontations with hostile actors, or the sight of police removing the posters.

Instead, she said, the community kept the posters in place the entire day, noticing the curiosity and empathy they sparked in passersby, and there were no confrontations. She shared video with JTA of passersby crouching to read the stories of the hostages, with some clasping their hands together in silent prayer.

“People prayed and people cried and people were just absolutely — they were riveted,” she said, getting emotional at the recollection. “In the end, we left them up for the entire day. Not one of those posters was torn down.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.