Speaking last week on Facebook, against the backdrop of his synagogue’s main sanctuary, Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz issued a blunt message about the New York City mayoral race: “The Mamdani policy initiatives will destroy New York City.”

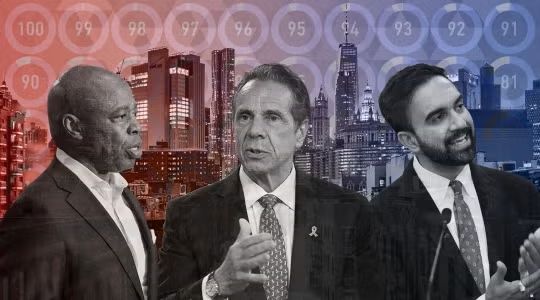

In the face of what he views as an imminent “catastrophe” if mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani is elected, Steinmetz believes the candidate polling second, former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, can win.

“The only way that we can beat Mamdani is if all of the registered voters show up at the polls,” he said in the video, which he posted on Facebook.

Steinmetz, who leads Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, a Modern Orthodox synagogue on the Upper East Side, said the video marked a sharp departure from his typical policy of avoiding politics in shul. And the change wasn’t because the Internal Revenue Service recently reversed a decades-long policy barring endorsements from the pulpit, he said.

“I’m generally against political endorsements, and I know that now it’s acceptable with the new IRS changes,” said Steinmetz. “However, to every rule, there is an exception.” Steinmetz added that he would also soon sign a letter of support for Cuomo alongside several other local rabbis, whom he declined to name.

Steinmetz is not the only New York City rabbi to be occupied by the looming mayoral election. A few have openly endorsed candidates, appearing with them at rallies. More of them are, like Steinmetz, wading into politics despite believing that it’s generally ill-advised to do so. Others say they are sticking to their non-partisan principles even as the election occupies and at times divides their communities. And some say that their congregants’ minds are so made up, there’s little reason for them to say anything at all.

Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz, the leader of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun, a Modern Orthodox synagogue on the Upper East Side, speaks in his synagogue urging voters to cast their ballots for mayoral candidate Andrew Cuomo. (Screenshot)

“There’s so much alignment on this that there’s really no debate over this race in terms of who we are not voting for,” said Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt, the co-founder and rebbetzin of The Altneu, another Modern Orthodox synagogue on the Upper East Side. Referring to Mamdani, she said, “The community is very organized and committed to electing anyone else, anyone but him.”

Mamdani’s deep criticism of Israel and its actions in Gaza have made him toxic not only in Modern Orthodox spaces, which lean conservative, but also among other pro-Israel Jews in the city. While polls show that Mamdani enjoys substantial Jewish support, much of it comes from Jews who identify as secular.

Still, some congregational rabbis have come out as supporting him — at least in their personal capacity.

Rabbi Rachel Goldenberg, the founder of Malkhut, a progressive, non-denominational congregation in western Queens, was the only current pulpit holder among six rabbis who co-authored a July op-ed saying they support Mamdani.

“We believe that Jewish safety will not be secured by demanding unconditional support for Israel or imposing litmus tests on public officials around language. It will be secured through effective policy, education, solidarity, and shared struggle. That is what Mamdani offers,” they wrote.

Throughout the mayoral race, Goldenberg said some of her congregants had approached her to say that they were “concerned” about Mamdani’s relationship to the city’s Jews and to ask whether she shares their worries. She said that while she and Mamdani “are not identical in our Israel-Palestine politics,” she did not share those congregants’ fears.

“I definitely try to reassure folks that I do think that the stirring up of fears around antisemitism are really coming from vested interests in defeating him, using Jewish fear and using the real rise of antisemitism to sow distrust in a Muslim candidate for mayor,” Goldenberg said.

But she also said she did not consider her op-ed to be a rabbinic endorsement for her congregation.

“This statement that I made was one as a Jewish leader in New York City,” said Goldenberg. “I think it’s important for me to use my position and my voice in public to speak, and it’s my right to do that, but I don’t campaign and make endorsements as the rabbi of my community.”

The endorsement calculus changed this year with the revision of the IRS regulations. But at least in non-Orthodox congregations, there is “pretty universal rejection” of the new latitude, according to Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism. This week, his group along with the organizing bodies of the Conservative and Reconstructionist movements issued new guidelines for rabbis urging them not to endorse candidates.

The guidelines warned that endorsing political candidates could risk “undermining our leadership and dividing our community,” and that they could also open up the door for political coercion, including “threats or promises from donors, elected officials, or interest groups for backing a candidate or party.”

Some New York City rabbis cited those concerns in explaining why they did not plan to make an endorsement in the mayoral election.

“We will not turn our synagogue into a place for political campaigns, and we will not open the door to the possibility that members may seek to use their donations to influence elections,” Rabbi Roly Matalon of the non-denominational synagogue B’nai Jeshrun on the Upper West Side wrote in an email.

Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch of the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, a Reform congregation on the Upper West Side, warned that the IRS ruling could cause politicians to be “tempted” to look at religious institutions as a source for funding and support, a dynamic he said would harm synagogues.

Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch of the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York City launched a new program called Amplify Israel, which he hopes will encourage Reform movement leaders to embrace Zionism even as they navigate a “deeply problematic and offensive” new Israeli government. (Shahar Azran/Stephen Wise Free Synagogue)

But Hirsch, who leads a Zionist organization within the Reform movement, said he would not be sidestepping politics from the pulpit even as he will not endorse.

“No matter what the IRS says, even assuming that they permit now clergy to speak whatever it is they want to say about support for political candidates, we’re not going to do that here, but we will be very engaged in the political process, especially about clarifying what our understanding is of Jewish values and their implementation in the policy dimension,” he said.

Hirsch said that for his congregants, there were three main areas of concern about Mamdani: his lack of “considerable executive experience,” his socialist policies and his “hostility to Israel.” But he suggested that his congregants did not all hold a single view and added that rabbis risk compromising their moral authority when they wade too deeply into partisan politics.

“When it comes to preferences for political candidates, every Jewish broad-based institution, generally, but especially in the American Jewish community, there’s a diverse spectrum of opinions,” he said. “As spokespeople for religious values … it diminishes us if we are perceived as being in a partisan camp.”

For some rabbis, neither the heated race nor the changes in IRS rules will get them to change their longstanding policies. Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of the Upper West Side Conservative synagogue Ansche Chesed said endorsing candidates would be an “inappropriate use of my rabbinic role.”

Others have engaged in a delicate balancing act. Rabbi Kyle Savitch, the founder of Kehilat Harlem, a non-denominational congregation in Harlem founded in 2017, said he has spoken openly with congregants about the mayoral election and, ahead of the primary in June, encouraged them to rank neither Mamdani or Cuomo.

“The most political I got was encouraging people to take advantage of the ranked choice voting system,” he said. “It was relatively clear that the two main candidates were Cuomo and Mamdani, and that I was encouraging people to take advantage of ranked choice voting, to choose neither.”

For the general election, Savitch is not making his preference known, though he said he reached out to Mamdani’s campaign to try to get a “firm statement on antisemitism” from the candidate. He didn’t receive a response.

“I have had conversations one-on-one with folks, with a lot of folks,” Savitch said. “I won’t say who I’m voting for or endorse anyone, but I will kind of talk openly about all the candidates and my feelings and thoughts and concerns, and listen to their feelings, thoughts and concerns also.”

Jacobs emphasized that rabbis should absolutely engage with their congregants on the issues and ideas that matter to each of them.

“If you’re a rabbi, you know how to talk about the issues of the day and the values that are most important to people,” said Jacobs. “You don’t need to mention a candidate or a name to be talking about the most important issues, but I think our job is to get deeper than the current pain going on on any given question or any race.”

Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt and Rebbetzin Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt of the Altneu, a Modern Orthodox synagogue on the Upper East Side. (Daniel Landesman)

But sliding too much into politics can take a toll, Chizhik-Goldschmidt said.

“We try to avoid political discussion here as much as possible, and I think that’s necessary for many congregants’ mental health,” said Chizhik-Goldschmidt. “I think it is different for a rabbi to post on their personal social media, for example, about politics. It’s different from hearing it from the physical pulpit.”

With seven weeks to go before the election and many opportunities on the way for rabbis to address their congregants — the High Holidays begin next week with Rosh Hashanah — it’s possible that more New York City rabbis will take a stand. Of the 40 rabbis of varying denominations across the city asked for comment for this story, most did not respond.

Some of the rabbis reached left open the possibility of a future endorsement. Rabbi Jonathan Glass, the leader of the Orthodox Tribeca Synagogue, and Rabbi Paula Feldstein, the leader of the Reform Hebrew Tabernacle of Washington Heights, each said they would not be endorsing a candidate “at this time.”

It’s not clear how much difference any rabbinical endorsements will make, particularly if Mayor Eric Adams drops out as his campaign has signaled he could. Steinmetz conceded that at Kehillat Jeshurun, there’s not really anyone for him to sway in a head-to-head matchup.

“In my congregation, this is so obvious, I don’t need to endorse Cuomo,” he said in an interview. “I think everyone knows everyone is voting for Cuomo, or almost everyone, but no one is voting for Mamdani, and so it’s really unnecessary.”

Still, Steinmetz felt a need to take a public stand.

“The specter of having a mayor of New York — the single city in the world with the largest Jewish population — be someone who is committed to the destruction of the State of Israel, who accuses Israel of genocide and threatens to arrest the prime minister of Israel if they come visit, I think that would be a catastrophe,” said Steinmetz. “And even though one should have a rule not to get involved in politics, that is not a rule that applies when something this awful can occur.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.