(JTA) — In 1983, the Italian-Israeli professor Sandra Debenedetti Stow stunned the scholarly world with an explosive article that proposed that Jews introduced pizza to the European diet.

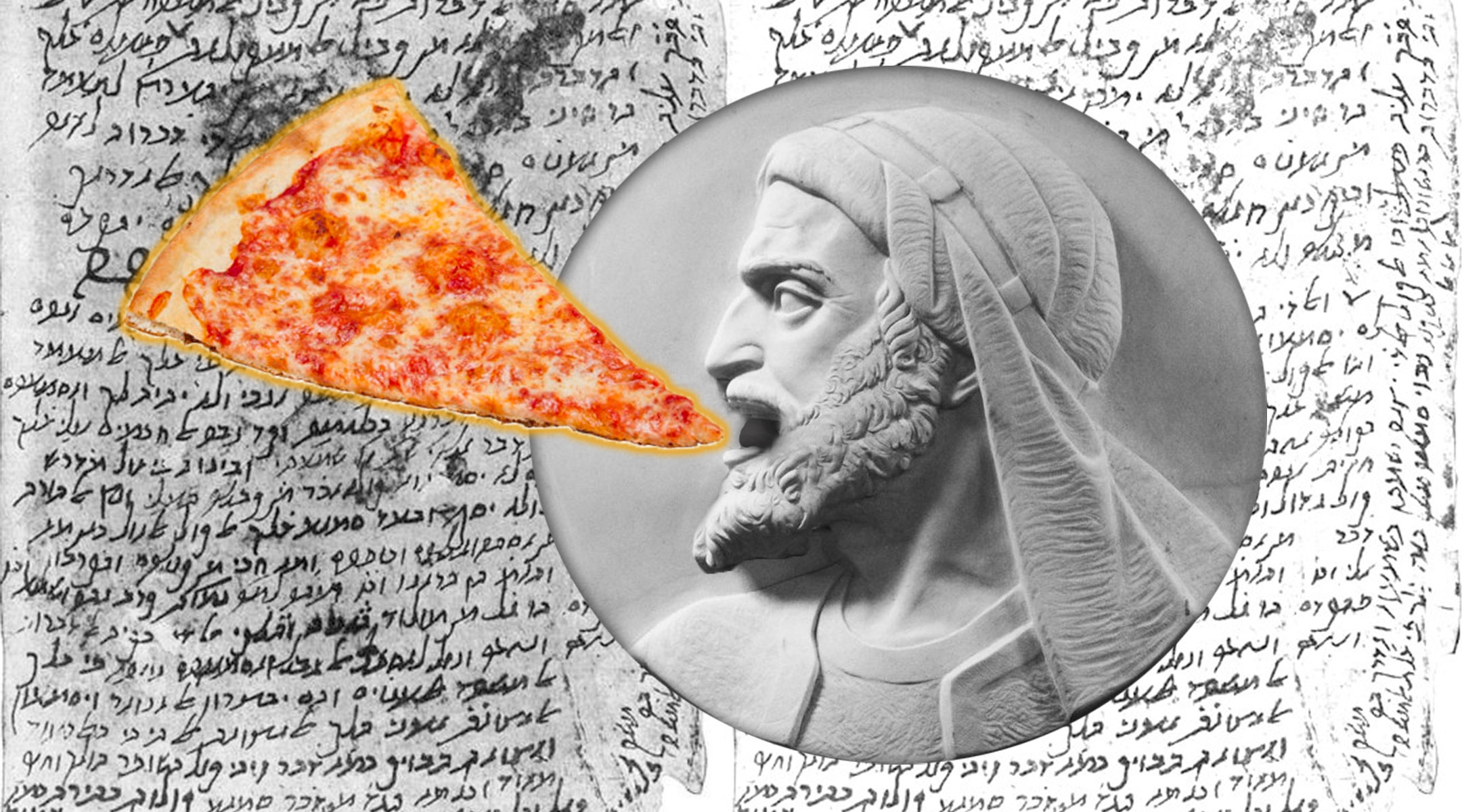

She cited Yehuda Romano, a 14th-century Hebrew scholar from Italy, who translated Maimonides’ use of the word “hararah” (a type of flatbread) in the Mishneh Torah with four simple Hebrew letters: peh, yud, tzadi and heh, or “pizza,” arguably the very first time the word was ever used in any language.

Before the leaven could rise, a new scholarly sub-field was born.

I tripped over this appealing historical fact while reading the catalog of the new National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah in Ferrara on the intermediate days of Passover (no doubt that my gustatory interest was partially fueled by the holiday). I was intrigued by the possibility that while oblique references to the aromatic staple of adolescent diets can be traced to ancient times, it was the Jews who first gave a name to the global delicacy.

The connection to Maimonides was also quite tempting – was his “hararah” really an Egyptian antecedent of Chicago deep-dish? A thousand questions erupted. Did Maimonides hold, asked Yechiel Goldreich on Twitter, with the “one slice mezonos, two slices hamotzi rule”? And if Rambam ate pizza, wondered Professor Jared Ellias, how did we Ashkenazim get stuck with gefilte fish and stuffed cabbage? Even my wife chimed in: “Finally — the end of challah tyranny!”

Unfortunately, it turns out the story is a little more complicated, and our ethnocentric glee was premature. A 10th-century Latin code from Gaeta explicitly mandates the donation of “twelve pizzas” to the local bishop every Christmas and Easter, antedating Romano’s reference to the word by 400 years and, incidentally, providing evidence of the very first pizza delivery service.

Writing in the journal Onomastics in Contemporary Public Space, Ephraim Nissan and Mario Alinei, perhaps hoping to redeem the Jewish antiquity of the doughy disc, pointed to the pizzarelle, possibly a cookie-sized version of pizza eagerly consumed by Jewish children in ancient Rome. The fact that pizzarele were served on Passover, however, diminishes its value for our purposes – if it isn’t chametz, it can’t be real pizza.

Nissan and Alinei vehemently dispute Oxford Professor Martin Maiden’s argument that the word “pizza” is of Germanic origin, deriving from the Old High German word “pizzo,” meaning “bite.” Maiden seems to gives little credence to the obvious association with pita bread, suggesting instead that the Mediterranean food was also influenced by Gothic vocabulary. Seriously.

After much research, I’m not much closer to really pinning down the origins of the word, but one thing is clear: Pizza, in one form or another, has been part of our diet as long as Jews have been turning over the kitchen after Passover. Who knows, even Maimonides himself might have enjoyed a slice or two.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.