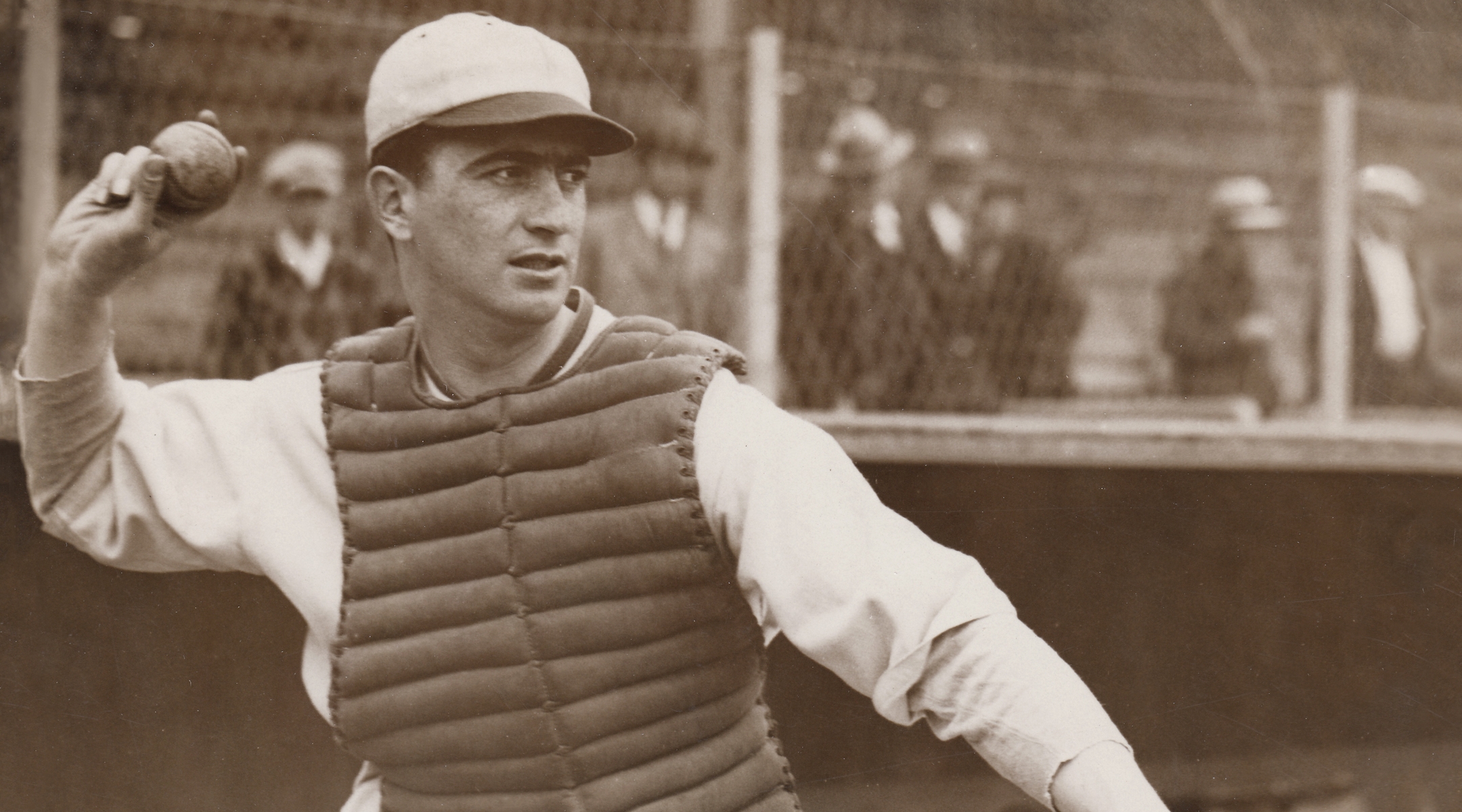

(JTA) — Moe Berg’s 15-year career as a major league shortstop, catcher and coach in the 1920s and ’30s wasn’t much to speak of, but his story keeps being told in about as many ways as there are to tell it.

A Columbia Law School graduate who played for the Chicago White Sox, Washington Senators, Boston Red Sox and others, Berg is best known for working as a spy for the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency, during World War II.

His exploits include intelligence-gathering trips to Italy and Switzerland to uncover secrets about the Nazi nuclear program.

Berg’s story has been told in a nonfiction book and a feature film, but veteran filmmaker Aviva Kempner thought his story also deserved a full-length documentary. “The Spy Behind Home Plate” is in selected theaters nationwide.

Kempner, who lives in Washington, D.C., and is the director or producer of four previous documentaries, spoke with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency via email.

JTA: The story of Moe Berg has been told at least twice before — in the 1994 biography by Nicholas Dawidoff, “The Catcher Was a Spy,” and in the 2018 scripted movie of the same name starring Paul Rudd. What does your documentary add to what we know about Berg?

Kempner: I had the advantage of incorporating 18 interviews conducted from 1987 to 1991 by filmmakers Jerry Feldman and Neil Goldstein for “The Best Gloveman in the League,” which was never completed. Their interviews were archived at Princeton, and The Ciesla Foundation supported digitizing them for use in “The Spy Behind Home Plate.”

Their archival interviews include Moe’s brother, Dr. Sam Berg; Berg’s fellow players center fielder Dom DiMaggio, and pitchers Elden Auker and Joseph Cascarella; fellow OSS members Horace Calvert, William Colby and John Lansdale. Two interviews with former OSS members Earl Brodie and Edwin Putzell, conducted by ESPN for its “SportsCentury-Moe Berg” biography, were also included.

I also think the courage and accomplishments of the OSS, our too short-lived intelligence agency, should inspire numerous feature films, more documentaries and even a heroic television series.

Your interest in Moe Berg’s story seems pretty natural — your previous films include “Partisans of Vilna” (1986), about Jewish commandos fighting the Nazis, and “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg” (1998), about the legendary Jewish baseball player. But what was the specific impulse that led you to tell Berg’s story?

Life-size wall hangings of my three favorite Jewish baseball players — Sandy Koufax pitching to Hank Greenberg and Moe Berg as catcher — adorn the curved wall of my home’s staircase. I was so proud of making “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg” because he was a Jewish hero during times of teeming anti-Semitism in America and while the Nazis were raging in Europe.

Businessman William Levine asked me after seeing “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg,” “Do you want to make a film on an unusual Major League Baseball player?” Levine pointed out that “Moe Berg was a great subject because he became a spy for the OSS during World War II, helping to defeat the Nazis.” I jumped at his generous offer to support a Berg bio film. “The Spy Behind Home Plate” fits perfectly into my goal to make historical documentaries about under-known Jewish heroes and my career focus on exploring courageous tales about those who fought the Nazis.

Berg is usually described as “enigmatic” — I’ve seen the famously eccentric baseball manager Casey Stengel quoted as describing Berg as “the strangest man ever to play baseball.” There was speculation on everything from his sexuality to how many languages he actually spoke. Is there a key interview or piece of evidence that you discovered that unlocked some of his mystery?

Nothing we could find verified he was gay. Quite the contrary, the interviews from 30 years ago with his fellow players point to Moe Berg being a lady’s man. Also, the documentary has testimony from Babe Ruth’s daughter, Julie Ruth Stevens, who danced with Moe on the ship to Japan in 1934. She talked about how he “came on to her.” And finally Paul Huni, the son of Estella Huni, who Moe had a relationship with for over a dozen years, talks about how they had a great love affair. He also provided photos of them together. Yet we could not find much footage of Moe actually talking, so he remains a mystery to some extent.

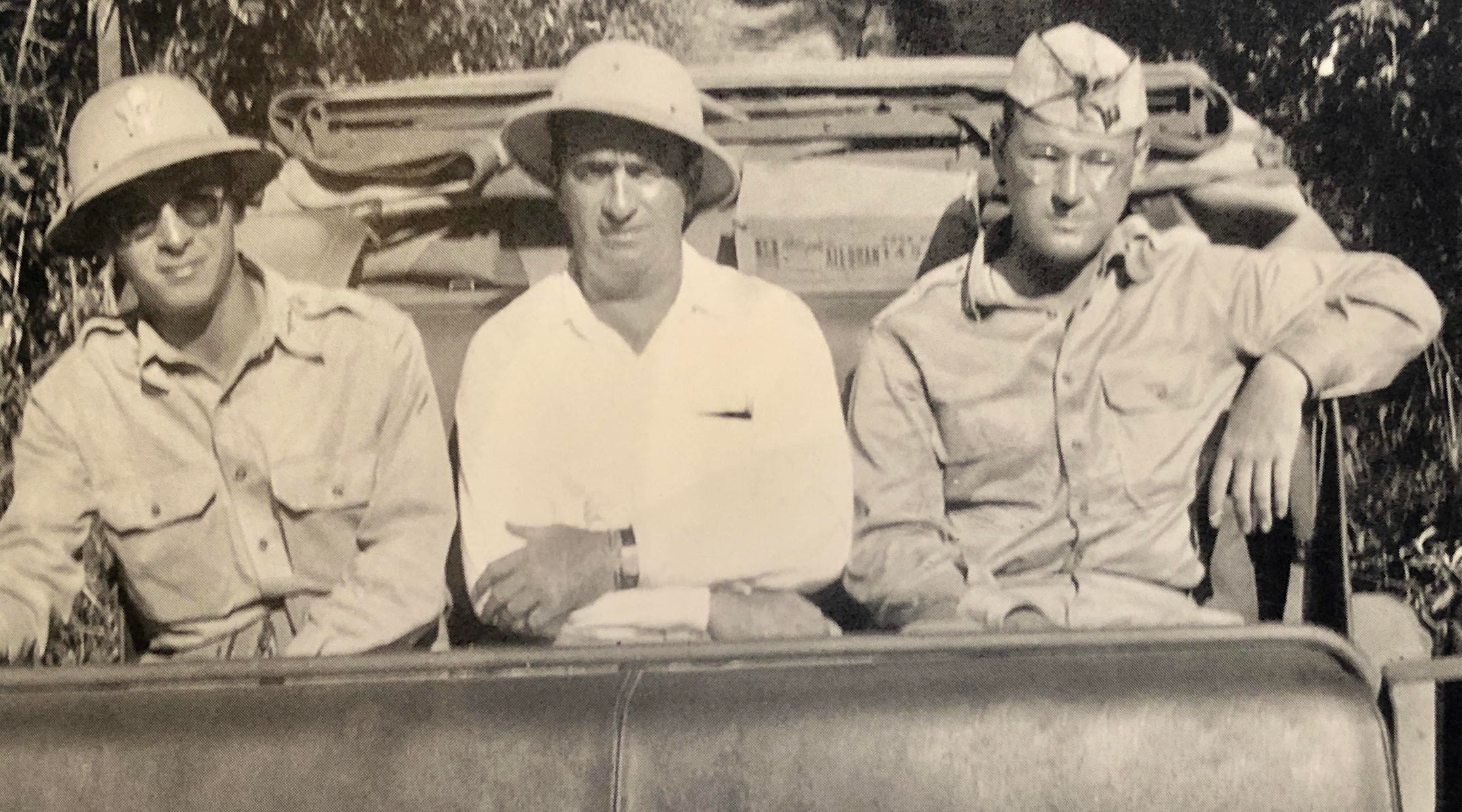

There are many myths and tall tales about Moe’s activities during the war, including the claim that he parachuted into Yugoslavia and met with partisan leader Tito. After extensive archival research, we found no evidence of this claim. Unfortunately, this story is featured in several museums and exhibits.

Moe Berg, center, is seen on a “goodwill” assignment in South America, August 1942. (Courtesy of Linda McCarthy)

In what sense is the story of Moe Berg — beyond the biographical facts of his being a son of immigrant Jewish parents — a Jewish story? Did he face anti-Semitism either as a ballplayer or a spy? And did he have an affirmative Jewish identity?

Moe Berg did not have a bar mitzvah but did know Hebrew and Yiddish among his many languages. While attending Princeton in the mid-’20s, when Jews were labeled “Hebrews” in the yearbook, Berg took a courageous stand of not joining a dinner club if other Jews were not allowed. While in the MLB Berg did not face the anti-Semitism that Hank Greenberg did as a slugger. And every day he was spying as a Jewish male in Europe during the war he was risking being caught and executed.

He is an American hero for sure.

You are the child of Holocaust survivors. Your first film, “Partisans of Vilna,” was I think the only one in which you approached the Holocaust directly, although I often notice that with some of your other subjects — Hank Greenberg, the comedian and actress Gertrude Berg, and Moe Berg — the Holocaust is hovering just outside the frame either as a presence or an absence. After “Partisans,” did you make a conscious choice not to make another direct Holocaust documentary?

After “Partisans,” I have concentrated on making films about the Jewish-American experience and their heroes. Also, it seems I like making films about subjects with Berg in their names. Seriously, I wanted to show Jewish heroes reflecting nonstereotypical roles and fighting the isms of fascism, sexism, McCarthyism and again Nazism. Hank Greenberg, Gertrude Berg, Julius Rosenwald and now Moe Berg are all those role models that are good for we as American Jews to revere and emulate.

You and I first met somewhere in between “Partisans” and “Greenberg.” I think I learned from you that documentary filmmaking is about 30 percent making the film and 70 percent fundraising. How do you get a funder excited about a project? Has it gotten any easier?

My 501(c)(3) produces my documentaries and yes it’s a challenge to raise the funds in a timely fashion. I am so lucky that after 40 years in the business that one angel came to the rescue to fund this film. In the past there have been dozens upon dozens of generous funders. I am just hoping there are other mensches like William Levine that want to support another Jewish hero or heroine.

Bonus question: What are you watching these days? Are there some new documentaries you think our readers shouldn’t miss?

There is a fun one called “The Mamboniks” about how Jews loved dancing mambo.

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.