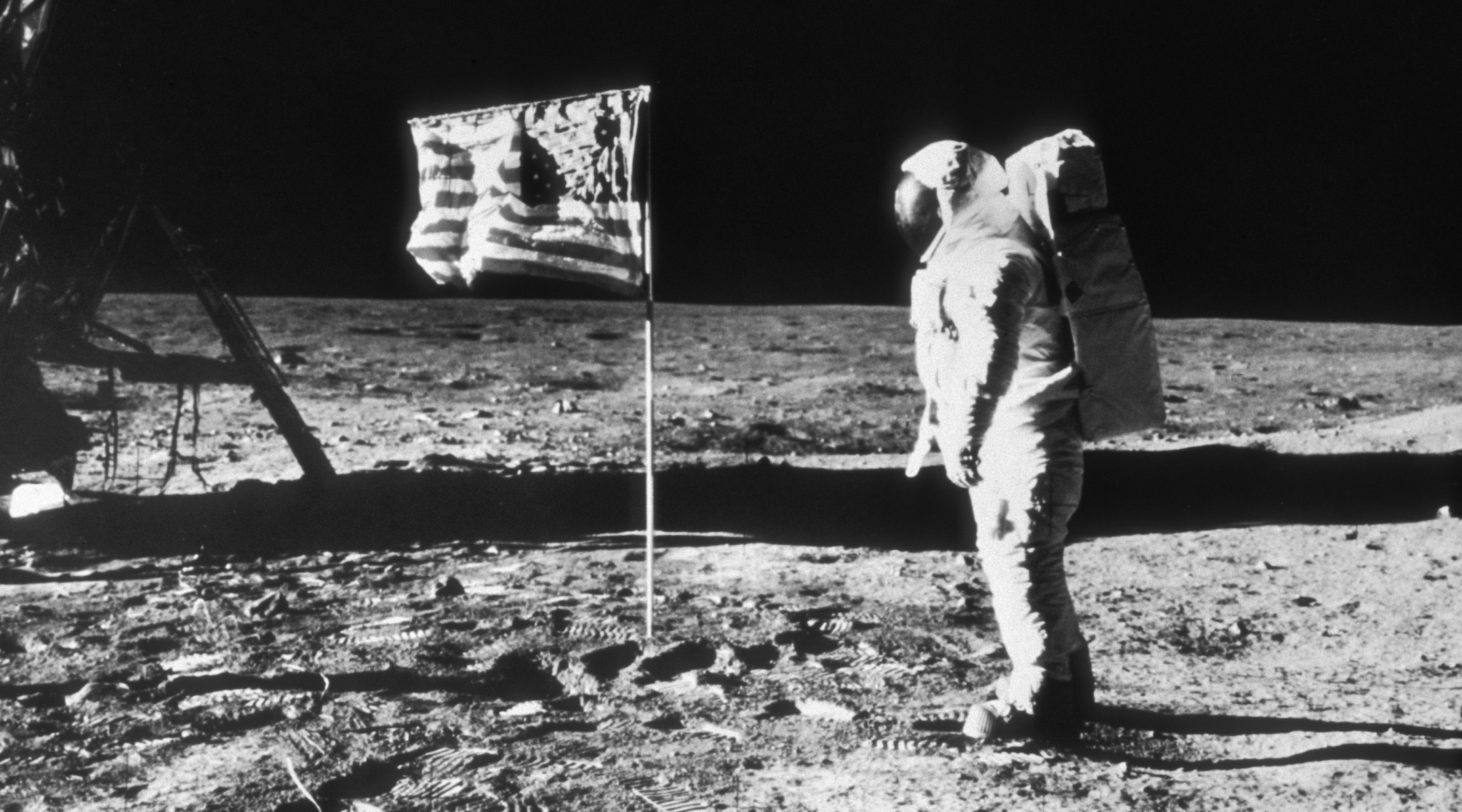

(JTA) — I watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon through one eye, the other glued shut by a stye. This was in the kitchen of our rented bungalow on the New York side of Lake Champlain, where we spent a month every summer. My parents had parked our crappy black-and-white portable TV on the kitchen table, and someone was no doubt futzing with the wire coat hanger that stood in for an antenna.

I feel it was past my bedtime, and I was wearing pajamas, and I was cranky about the whole thing with the stye and all. If I remember being truly excited about the first humans on the moon, I think it might be a bit of confabulation. It was only in the next few years that I’d get really excited about the space program. I found out you could write a fan note to NASA and they would send you a thick envelope of swag related to the latest mission. It would include color glossies of the crew, maybe a facsimile of the patches they wore and — oh bliss — a foldout map of the moon.

The coolest thing was a floppy plastic phonograph record of the audio of Apollo 11’s landing on the moon. It’s a tense few minutes of scratchy voices, and I played it so often I committed it to memory.

Aldrin: Lights on … Down 2 1/2. Forward. Forward. Good. 40 feet, down 2 1/2. Kicking up some dust. 30 feet, 2 1/2 down. Faint shadow. 4 forward. 4 forward. Drifting to the right a little. OK. Down a half.

Mission Control: 30 seconds [of fuel remaining].

Armstrong: Forward drift?

Aldrin: Yes. OK. Contact light. OK, engine stop.

Armstrong: Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

Mission Control: Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

I was enthralled by that as an 11-year-old, and even more so this week as I binged on documentaries marking the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s successful mission. The technological unlikelihood of the entire space program, the mustering of national will to go from essentially zero to moon in less than a decade, the collective vision and problem solving to achieve what still looks like an unachievable task. If it feels like ancient history, that’s not just because it was five decades ago. I imagine anyone who has no direct memory of the moon landings can’t even imagine what it means for our federal government to set an audacious goal and achieve it.

The best of the retrospectives, especially the three-part “Chasing the Moon” series on PBS, don’t mythologize this vast public undertaking or minimize its costs. “Chasing the Moon” emphasizes that billions of dollars were being spent on beating the Russians to the moon while American cities burned and young men were dying in Vietnam. An audio clip of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. is every bit as awe inspiring as video of a Saturn V launch: “If our nation can spend $35 billion a year to fight an unjust evil war in Vietnam, and $20 billion to put a man on the Moon, it can spend billions of dollars to put God’s children on their own two feet, right here on Earth.”

There are also reminders that the space program wasn’t the bipartisan, national kumzitz that we like to remember it as: Rocket plants and mission headquarters were put in Southern states to buy the support of Southern lawmakers; an African-American pilot was kept out of the astronaut program to placate their constituents; Wernher von Braun, the ex-Nazi who built the Saturn V, spun tall tales to convince Congress and the public that the moon shot wasn’t first and foremost an attempt to one-up the Soviets.

I’m old enough that I am not only feeling nostalgic about the moon landing but nostalgic for the nostalgia. This year is also the 20th anniversary of “A Walk on the Moon,” Tony Goldwyn’s film about romance and infidelity set in the summer of 1969. Diane Lane plays a Jewish housewife spending her weekdays without her husband at a Catskills bungalow colony, and Viggo Mortensen plays a hunk who tempts her into an affair. The moon landing forms the backdrop.

A Jewish bungalow colony! The moon! Except for the whole infidelity thing (as far as I know, anyway), the entire film plays like my home movies. There’s even an eerie moment depicting a very specific event from my own childhood (a kid steps on a hornets’ nest, and all of the colony’s women administer to him with ice cubes).

Woodstock also took place that summer, not far from the bungalow colonies. It barely registers on the staid middle-class Jews in the film. I remember the screenwriter of “A Walk on the Moon,” Pamela Gray, saying that while everyone else was experiencing the 1960s, her parents’ generation was still living in the ’50s.

But not for long. The ’60s caught up with everyone. We gained more than we lost: women’s rights, civil rights, cleaner air, cleaner water, better health, the end of a pointless war. But we lost a lot, too: a sense of national purpose to solve our common problems; a deep respect for science over politics; a revelation, experienced by all the astronauts, that earth is a fragile, lonely and lovely thing and our only home. Imagine if we could muster the spirit of the Apollo program not for jingoism but, say, to tackle climate change.

(This is the point in the old joke where a genie says, “Let me take another look at that moon map.”)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.