Joey Weisberg and Molly Weingrod have four children, live in a city with a vibrant Jewish community and believe strongly in the importance of a Jewish education.

But when their kids reached school age, the couple decided against enrolling their children in a Jewish day school — or public school, for that matter.

They’re a homeschooling family.

“We just wanted to be with our kids when they were young because we knew it wasn’t going to last forever, and we both have had flexible work lives,” said Weingrod, a former day school teacher and administrator who now teaches “mindfulness-based” parenting classes to expectant parents. She and her family live in Philadelphia and describe their Jewish affiliation as “non/post-denominational.” We wanted our kids “to have space and time to be bored, and to follow their own interests and self-direct a much as possible, rather than being directed.”

To make sure their kids have a strong Jewish background, they build it into their day alongside secular studies.

Every morning begins with Jewish prayer. The kids study Torah two or three times a week, often using workbooks from Chabad called “Children’s Torah” and online resources like videos from AlephBeta.org. The two older children study Mishnah via Facetime with a cousin who’s a rabbi. One child participates in a virtual beit midrash class with other homeschooled kids in Maryland and Pennsylvania and led by a hired teacher.

“There is embedded in our tradition a sense of that it is our responsibility to teach our children Torah,” Weingrod said, explaining her preference for homeschooling. “We teach them to swim. We teach them Torah. We teach them the Pesach story. There’s this clear commandment that we’re responsible for their education.”

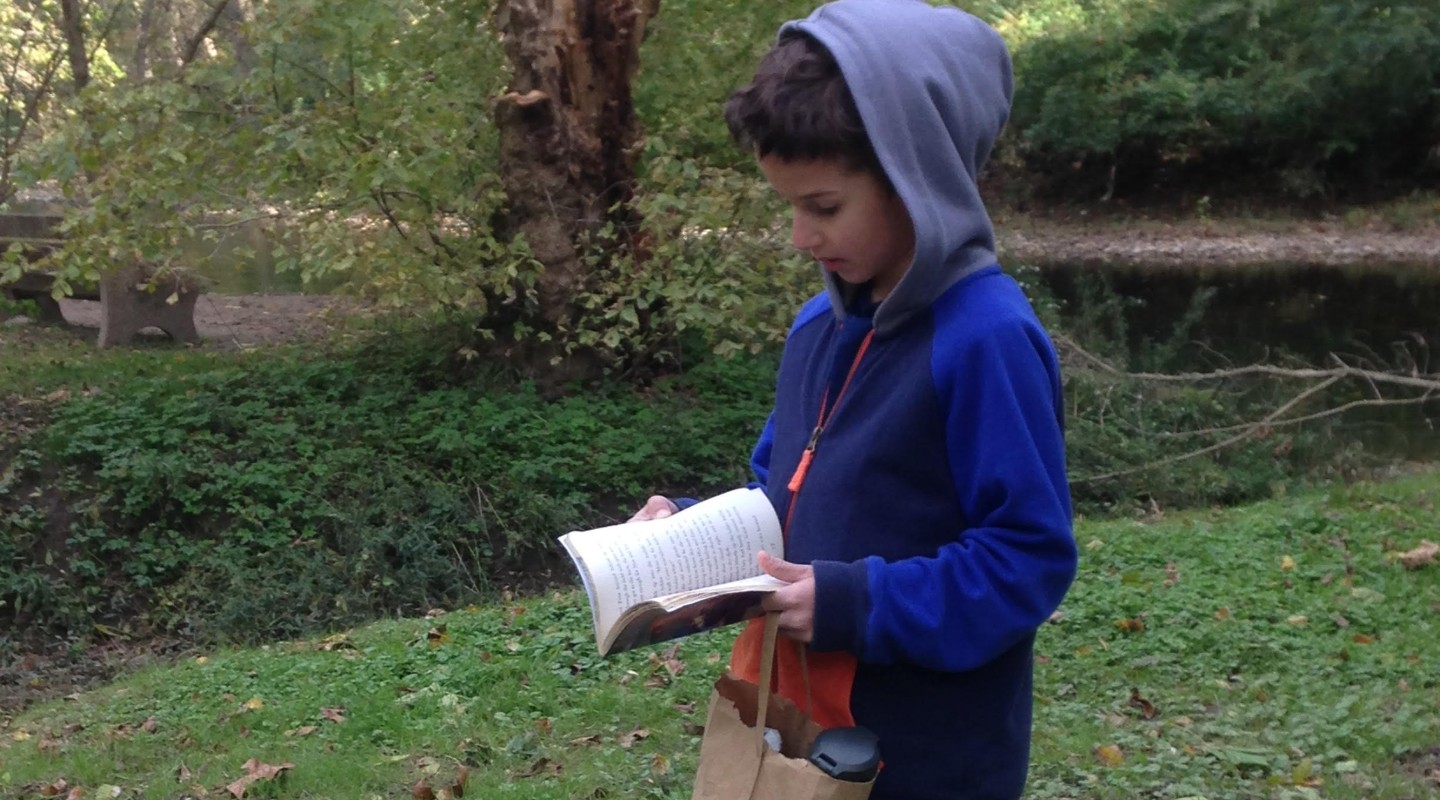

Molly Weingrod’s four children, including her son, are homeschooled. She and her husband wanted their kids “to have space and time to be bored, and to follow their own interests and self-direct a much as possible, rather than being directed.” (Courtesy Molly Weingrod)

With the homeschooling movement in America expanding rapidly, a growing number of Jewish education-minded families are keeping their kids home. They include parents wary of formal classroom settings, families who live far from Jewish day schools or schools that comport with their religious orientation or values, and parents seeking to give their kids a Jewish education without paying parochial school tuition.

“People are very frustrated with the system,” said Chaya Margolin, director of Jewish Online School, a Chabad project that offers distance-learning classes. “Costs are getting higher and higher. Nothing has changed in 100 years between the stress of finances and learning that’s up to par, so we do it ourselves.”

Over the last five years, the Chabad program has grown from 40 to 200 students. Many students are the children of Chabad “shluchim” — Jewish outreach emissaries who live in far-flung places around the globe, which often have no local Jewish schools. But the program also fields many inquiries from non-Orthodox families seeking alternatives to traditional day schools or Hebrew schools.

An estimated four to eight million American children are being homeschooled, according to J. Allen Weston, executive director of the National Homeschool Association. Recent years have seen “very explosive growth,” he said.

Weston attributes the increase to rising dissatisfaction with public schools’ emphasis on test prep, curricula and traditional educational models.

Modern Orthodox mother Carmiya Weinraub has five children, the eldest of whom is approaching bat mitzvah. Weinraub decided early on she didn’t want her kids in public school, where kosher and Sabbath restrictions would inhibit their social life.

But she wasn’t excited about day school either, due to cost and what she described as their racial and socioeconomic homogeneity. She also was skeptical about day schools’ ability to endow her kids with a spiritual sense of God.

Weinraub soon discovered that Rockville, Maryland, has a thriving Jewish homeschooling community, and she and her husband relocated there from New York City. In Rockville, she says, her kids are not quite the fish out of water they’d be in another Orthodox community.

A former Hebrew teacher and synagogue youth director, Weinraub handles Jewish studies instruction herself. After her kids master reading English, she starts them on Hebrew with the help of a workbook. Weinraub and her husband model Jewish prayer daily, use the holidays to introduce lessons on Jewish history and tradition and for one of their children use the same online beit midrash program as Weingrod’s child uses. Of course, they spearhead the kids’ secular studies, too.

“It’s a little bit fly-by-the-seat-of-my-pants, a little bit hit-or-miss, and a little bit calculated,” Weinraub said. “We write thank-you notes, and that’s how they learn to write letters. We have a typewriter and they write stories. We have games available; Scrabble is how one kid learned how to spell. Our elevator is how one kid learned how to count.”

There are a variety of curricula for Jewish homeschoolers who crave more formality. The Lookstein Center for Jewish Education at Bar-Ilan University offers nearly 500 lesson plans and resources used both by school educators and homeschoolers. Mindful of the growing homeschool population, the center also runs the Lookstein Virtual Academy, a project-based accredited online program for middle- and high-school students.

Parents also use iTal Am—a computer-based Hebrew and Jewish heritage program, the correspondence project from the NSW Board of Jewish Education, materials from Jewish educational websites like Chinuch.org and even PJ Library, which mails free Jewish-themed books to homes.

Brooklyn mom Kate Fridkis, a lay cantor who identifies as Conservative and works at a Reconstructionist synagogue, hadn’t really planned on home schooling her 5-year-old. Last fall, she and her husband enrolled their daughter in kindergarten at a local pluralist Jewish day school. But the child became increasingly anxious and unhappy, and complained about the smallish classroom with a small number of female classmates.

Fridkis, who was herself homeschooled until college and recalls her childhood as “amazing,” found a local group of homeschoolers who encouraged her to take the leap. They spanned the gamut from freeform, “unschooling” parents to families with home-based classrooms featuring chalkboards on the walls. Their kids appeared happy and thriving.

While she loves the flexibility of homeschooling, Fridkis says she’s intimidated about shouldering all the responsibilities for her daughter’s Jewish education.

“As a parent, I wonder: How do I give my child the foundation I want her to have to go out into the world? How do I give her the tools?”

Though Fridkis knows Jewish liturgy and studied Hebrew in college, she’s not fluent. For now, she incorporates elements of Jewish life into her daughter’s new daily routine, from singing morning prayers to talking about the Jewish holidays. Down the road, she said, she may hire a Hebrew tutor or an Israeli babysitter.

“I try to in general talk to her about what it means to be a Jew in the world,” Fridkis said. “We’re not having deep philosophical conversations, but I’ll talk about tikkun olam, that as Jews we want to take care of other people.”

Meanwhile, both Fridkis and her daughter are adjusting to the new normal.

“There’s something really gratifying and cool about being able to step out of the childhood rat race and say: Okay, we’re doing math and also it’s a beautiful day — let’s go outside and look at some flowers,” Fridkis said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Avi Chai Foundation, which is committed to the perpetuation of the Jewish people, Judaism and the centrality of the State of Israel to the Jewish people. In North America, the foundation works to advance the Jewish day school and overnight summer camp fields. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.

More from Avi Chai Foundation