MEXICO CITY (JTA) —More than 10 years ago, Ilan Stavans scandalized language purists of the Spanish-speaking world by translating a chapter of “Don Quixote” — into Spanglish.

Since then, the so-called czar of Latino culture has become one of the most important interlocutors for Hispanics in the United States.

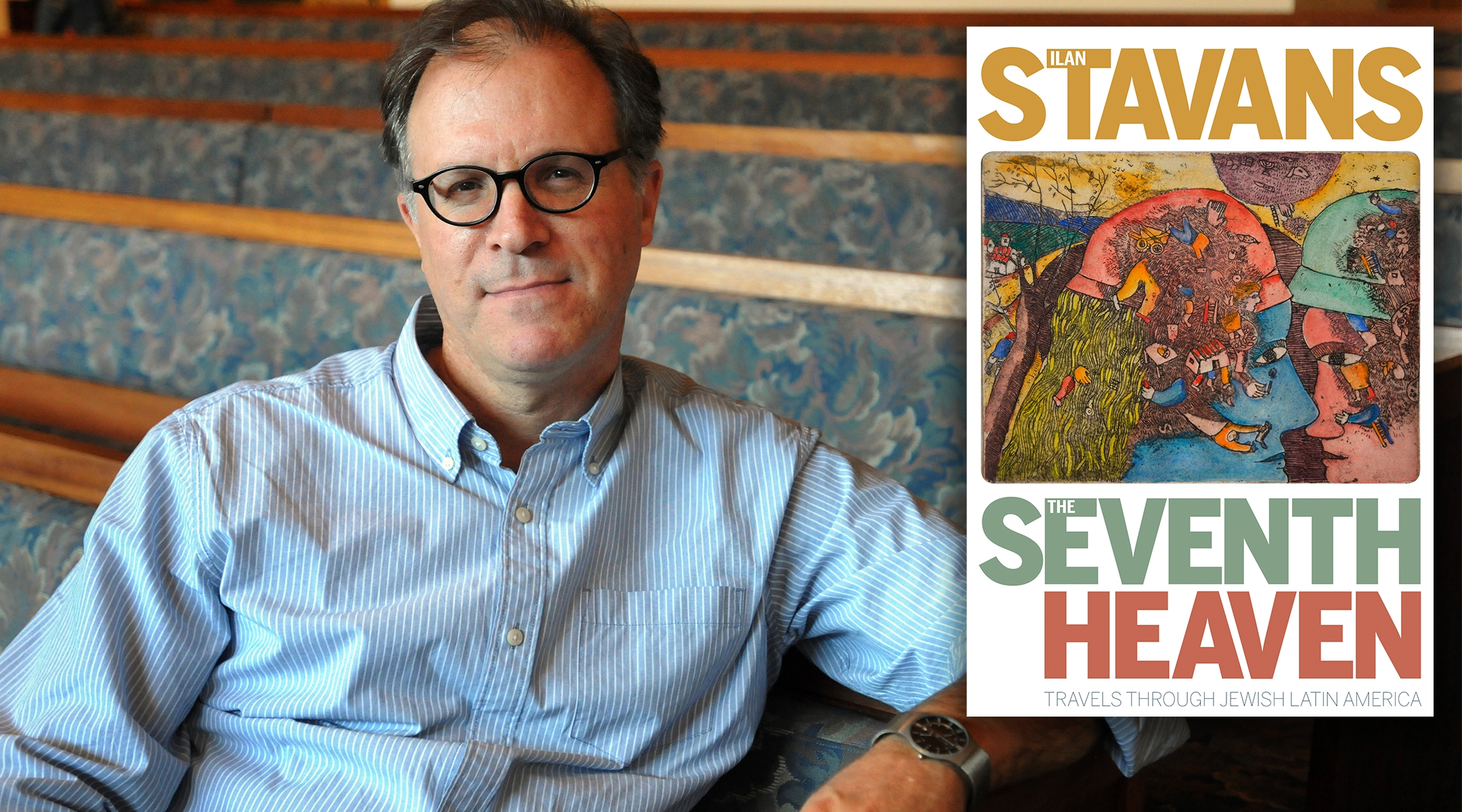

In his latest book, “The Seventh Heaven,” published earlier this month, the Mexico-born Stavans shares a travelogue of a trip through Jewish Latin America, a topic on which he has emerged as a leading expert in recent decades.

“Very few people know about Latin American Jews, including Jews in Latin America, who know about their own communities but not necessarily about those in other Latin American countries,” he said.

Stavans spoke to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on some challenges facing Latin American Jews today and his efforts to represent them to a global readership.

JTA: Tell me about how this book was conceived.

Stavans: This book is an attempt to explore the complexities of Jewish Latin Americans during a relatively peaceful and productive period, but in the midst of possible rapid and frightening changes.

It was inspired by a book by S. Ansky, the author of “The Dybbuk.” Ansky was an ethnographer who traveled around the Pale of Settlement at the very beginning of the 20th century. He left an astonishing document on the Jewish communities that lived in shtetls of Eastern Europe before they were wiped out by history.

With my insider’s knowledge as a Mexican Jew and an outsider’s view as a Latino living in the United States, I wanted to create a literary, ethno-anthropological artifact — a travel book of this community.

The book is written in English on purpose: I wanted to create a book that was coming from the inside to the outside, with a choice of language connected with the global vision of Jewishness. Yiddish used to be the lingua franca of Ashkenazi Jews, and there has been a suggestion that English is the Yiddish of the 21st century.

What are some of the tangible challenges that Latin American Jews are facing today?

The answer depends on the country. The small Jewish community in Venezuela has been the direct target of state-sponsored anti-Semitism since Hugo Chavez came to power. Synagogues have been desecrated. Cuban Jews under communism benefit from the goodwill of Americans and other foreigners.

The left in many countries is attached to the Palestinian cause, in some cases to extremist views and anti-Zionism runs rampant, often metastasizing into anti-Jewish sentiment. Synagogues and cultural institutions require high security. Various economies, such as that of Argentina, are in disarray.

Emigration to Israel, the United States and Europe decimate Jewish communities all across the continent, as does assimilation. Kidnappings, although dramatically less than a couple of decades ago, are still worrisome. Self-defense groups are well organized.

On the other hand, there is a growth of Orthodox communities. Jewish education continues in a solid way among the young, as do cultural organizations. Latin American Jews are polyglots who travel the world and have increasing political, economic and cultural influence everywhere.

Do you think Latin American Jews are at a similar turning point as the communities that S. Ansky documented?

The book doesn’t really try to establish the fact that what happened in the Pale of Settlement is exactly what is happening for Latin American Jews now. The conditions of the Pale of Settlement one century ago are very different from those of Latin American Jews today.

Latin American Jews are modern, 21st-century Jews. Many of us are assimilated, and religion doesn’t play the role it played a century ago. Also, each of the countries — Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Cuba — has its own metabolism and responds to its own forces. It would be a sweeping statement to say that it is the very same landscape.

As a Latin American Jew who has been living in the United States for more than half of your life, what do you think is the common misconception of Americans and American Jews about Latin American Jews?

American Jews living in the United States have a very limited view of anything that’s not about themselves. The fact that there are Mexican Jews, or Colombian Jews, is totally exotic for them — it is as if we are coming from Mars.

For Americans in general, there’s an impression that Latin America is a homogeneous — Catholic and mestizo (mix of Spanish and indigenous) — country. But Latin America has been a land of immigrants since the beginning with the arrival of the Spaniards and Portuguese. There are Jews, Japanese, Russians and Scandinavians and many other minorities living in Latin America right now.

American Jews have been very successful in the United States. But the tragic and dramatic aspect of this is the high rates of assimilation. In Latin America, because of the ethnic and religious dynamics, there’s less assimilation. The loss of members to the tribe is smaller; Jews have a more devoted sense of tradition, culture and identity. This, in many cases, turns the initial curiosity (“Are there Mexican Jews?”) into envy: Crypto-Jews like Luis de Carvajal are seen as heroes for sticking to their faith.

How much do the categories of “Latino” and “Hispanic” — as conceived in the U.S. — influence the way people look at Latin America and Latin American Jews?

Given the astronomical amount of immigration of Latinos to the U.S. (there are 60 million Latinos in the United States, more than most Latin American countries), the desire to have a common ground and common elements pushes people to understand certain characteristics as unifying.

Latinos look to each other and feel connected to certain historical heritages and common language. Once they come together, they create a sense that everybody is like them.

Most Latinos in the United States are from Catholic, Protestant or nondenominational backgrounds. The portion of Jews within the Latino group is minuscule, and because that portion is well-off and well-educated — and connected to the Jewish community at large — it has a relevance and a power that is very noticeable.

What is happening right now in the United States is a fascinating connection between the Latino community and the Jewish community, and the bridge between them is the Latino Jews.

How does Latin American Jewish history fit in larger Jewish history?

I think American Jews are exhausted with certain topics, like Israel and the Holocaust, and Jewish Latin America offers an alternative way to look at history and politics as well.

Though we have been considered a non-important chapter in the history of modern Jewish civilization, I think that with the growth of Latin America and Latinos in the United States, the role of the Jewish community in Latin America will be increasingly crucial to understanding Jewish history.

My book is part of the effort to expand the narrative of Jewish history. There’s a simplistic Zionist narrative which turns us Latin American Jews into “ethnic Jews,” and in which everything needs to end in Israel.

But the fact is that Latin America has been, in many ways, the Jewish promised land. Argentina competed with Jerusalem and the British-protected Palestine as a place where the Jewish state could have been established. Jewish communities in Colombia, Argentina and Mexico are thriving.

What are the challenges of writing about Latin American Jews in the United States?

At this point in my life, I can’t tell you anymore if I’m Mexican or American — if English or Spanish is “my language.” But I think that this is the experience of thousands of Jews in the Diaspora.

I think that being out of context is a Jewish condition, not quite in and not quite out, always dislocated. I wanted the book to create that impression. In my perspective we are translated and travelers by definition. If my book can create this empathy with dislocation, I would be happy.

This interview has been edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.