(JTA) — Renee Godinez had completed nearly all the steps to becoming Jewish before the coronavirus pandemic descended earlier this spring.

She had studied extensively with Rabbi Rick Winer of Temple Beth Israel in Fresno, California, and adopted Jewish practices in her life. All that was missing was a ceremony to mark the end of the conversion process.

Traditional Jewish law requires a meeting with a beit din, a court usually made up of three rabbis, and immersion in a ritual bath called a mikvah, which are now closed for most purposes because of coronavirus concerns. But because Godinez was converting under the supervision of a Reform rabbi, immersion was optional.

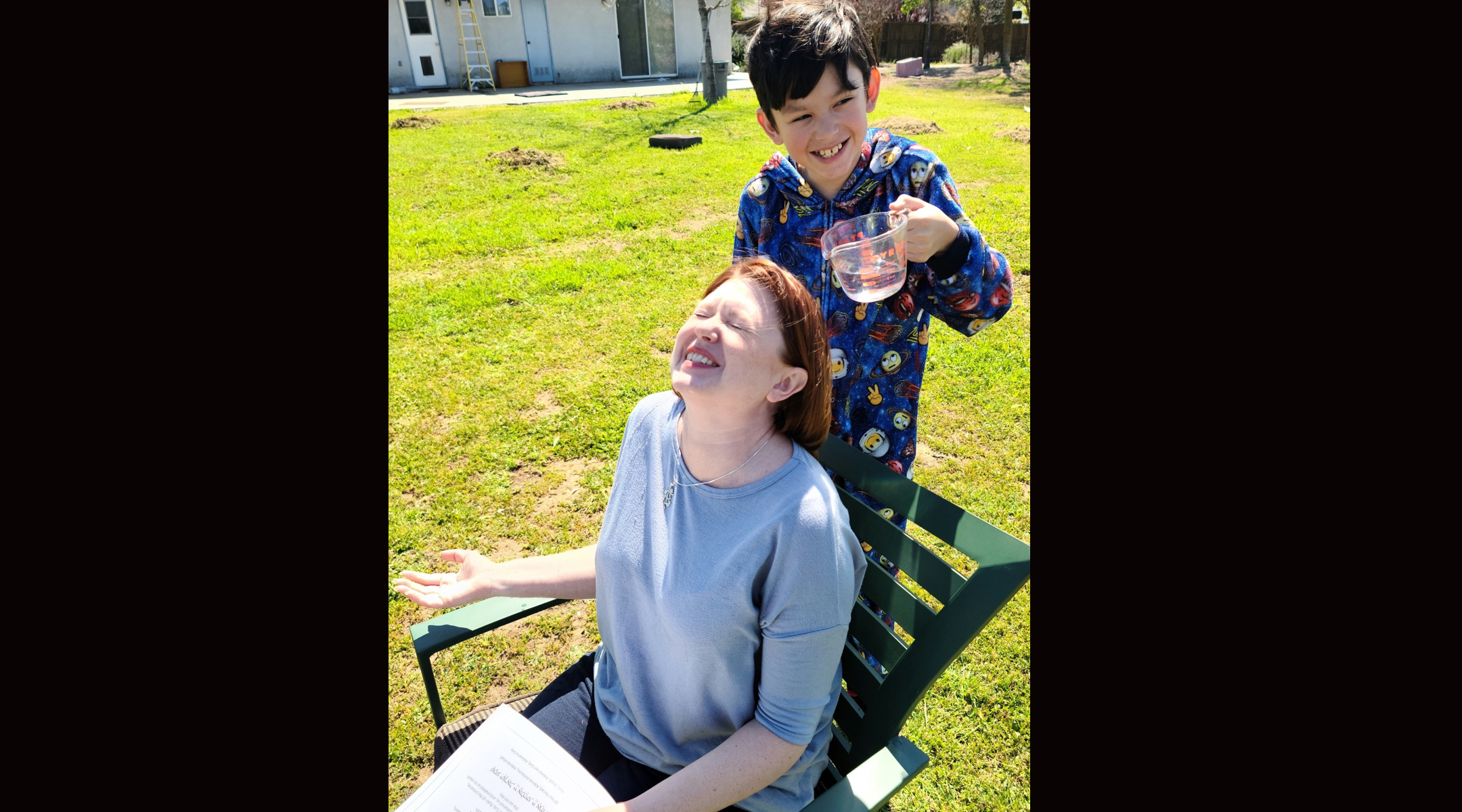

“I figured, OK, living waters are the key to mikvah, so I asked if they had any spring water,” Winer recalled.

She did indeed, and so after having met with a virtual beit din, Godinez, a 42-year-old mother of two, sat on a chair in her backyard as her 11-year-old son poured a bottle of spring water over her head.

Though the experience was unconventional — she was clothed and did not immerse her entire body in water — the experience was a powerful one for Godinez, who will immerse in a traditional mikvah once it is safe.

“It made it meaningful and in a way I’m really grateful for that,” she said. “Under the circumstances I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Mayyim Hayyim, a community mikvah in Newton, Mass., closed its doors to prevent coronavirus transmission. (Courtesy of Mayyim Hayyim)

Many Reform rabbis do require mikvah immersion, and for the thousands of people converting to Judaism by working with Conservative and Orthodox rabbis, getting creative isn’t an option. For them, stay-at-home orders, social distancing rules and mikvah closures have meant hitting pause on the extended, emotionally involved process of becoming Jewish.

The delays are forcing those who have been working toward conversion to weather a global crisis with a core piece of their identities unresolved and to grapple with a number of practical difficulties, including how to continue their involvement in Jewish ritual and communal life at a time of social isolation.

Liz Sczudlo is one of them. Sczudlo, a Los Angeles screenwriter, has known for years that converting to Judaism was in her future. Even before she and her Jewish husband tied the knot in 2017, the two had agreed that they would raise their children in his faith.

So when the couple got pregnant in the fall, she signed up for a conversion class that would allow her to finish in the spring before her due date in June.

Those classes have moved to Zoom. But Sczudlo, 34, won’t be able to complete the conversion before the birth. Instead, she and her daughter will have to convert at some point when it is safe.

“I sort of fluctuate between the grief and mourning for not getting to have the future we were envisioning and then also just [remembering] we’re so fortunate in so many other ways,” she said.

Sczudlo is studying through the Miller Introduction to Judaism Program at American Jewish University in Los Angeles, the largest program in North America for people exploring conversion.

“The general approach has been that learning is continuing, though the ceremonial, official parts of conversion have mostly been put on hold,” said Rabbi Adam Greenwald, who runs the program.

Liz Sczudlo had been planning to convert before she and her husband, Kenny Bravman, had their first child. (Emily Reuter/Anna Delores Photography)

For Sczudlo, not being able to complete her conversion as planned has brought a number of worries. She feels anxious about the thought of immersing her baby in water and finds herself contemplating worst-case scenarios related to giving birth before becoming Jewish.

“In the very slim chance if something happens in the very first few weeks of life and we were not able to convert our baby, if there’s a tragedy, did our baby never get to be Jewish?” Sczudlo said. “Obviously hoping for a healthy, happy baby and that that won’t even be an issue, but it’s hard not to run through all those different scenarios in my mind.”

She also wonders about how having had to convert will affect her daughter’s identity.

“Technically she will have converted to Judaism, so does that change who she is and what her Jewish identity is?” she said.

Things are still up in the air for the approximately 18 people who were supposed to complete their conversions in June through Anshe Emet Synagogue, a Conservative congregation in Chicago.

Cantor Elizabeth Berke, who leads the program, hopes that she will be able to at least do the beit din appointments in June — possibly virtually — and do the mikvah later if need be. And she said that doing immersions in the nearby Lake Michigan — since natural bodies of water can be used as a mikvah — may become a possibility.

Berke said her students are understanding of the fact that their conversions may be delayed.

“I think they realized this is a really unusual time and everybody is kind of hanging back and being patient,” she said.

Those who are converting to Orthodox Judaism face additional challenges. Shabbat observance is central to a traditional Jewish lifestyle but can be difficult to do alone.

“The practices are most optimally accomplished in the context of community, so you don’t have that in-person community,” said Rabbi Elie Weinstock of Congregation Kehilat Jeshurun in New York.

He has tried to reassure his conversion students, some of whom feel frustrated about not being able to move forward according to plan.

“Where you’ve been making progress before, now you’re standing still and treading water, and we need to find ways to communicate and continue to encourage people,” he said.

Bobby Apperson, a musician living in Fallbrook, California, had planned to convert on his 40th birthday in March with the rabbi of Nefesh, the nondenominational minyan he attends in Los Angeles.

“It just seemed like such a great marker, such a milestone,” he said.

Bobby Apperson was disappointed not to be able to convert on his 40th birthday but says that hasn’t stopped him from becoming more involved with his minyan. (Courtesy of Apperson)

Though the pandemic precluded that from happening, Apperson has enjoyed continuing to be involved in his minyan by attending virtual weekday and Shabbat services as well as starting to help out with social media.

“[Converting on my birthday] would’ve been really beautiful ceremonially,” he said. “But at this point I get to be more a part of the community and more of service to the community, and learn more about different aspects of the community and communities really, before going in.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.