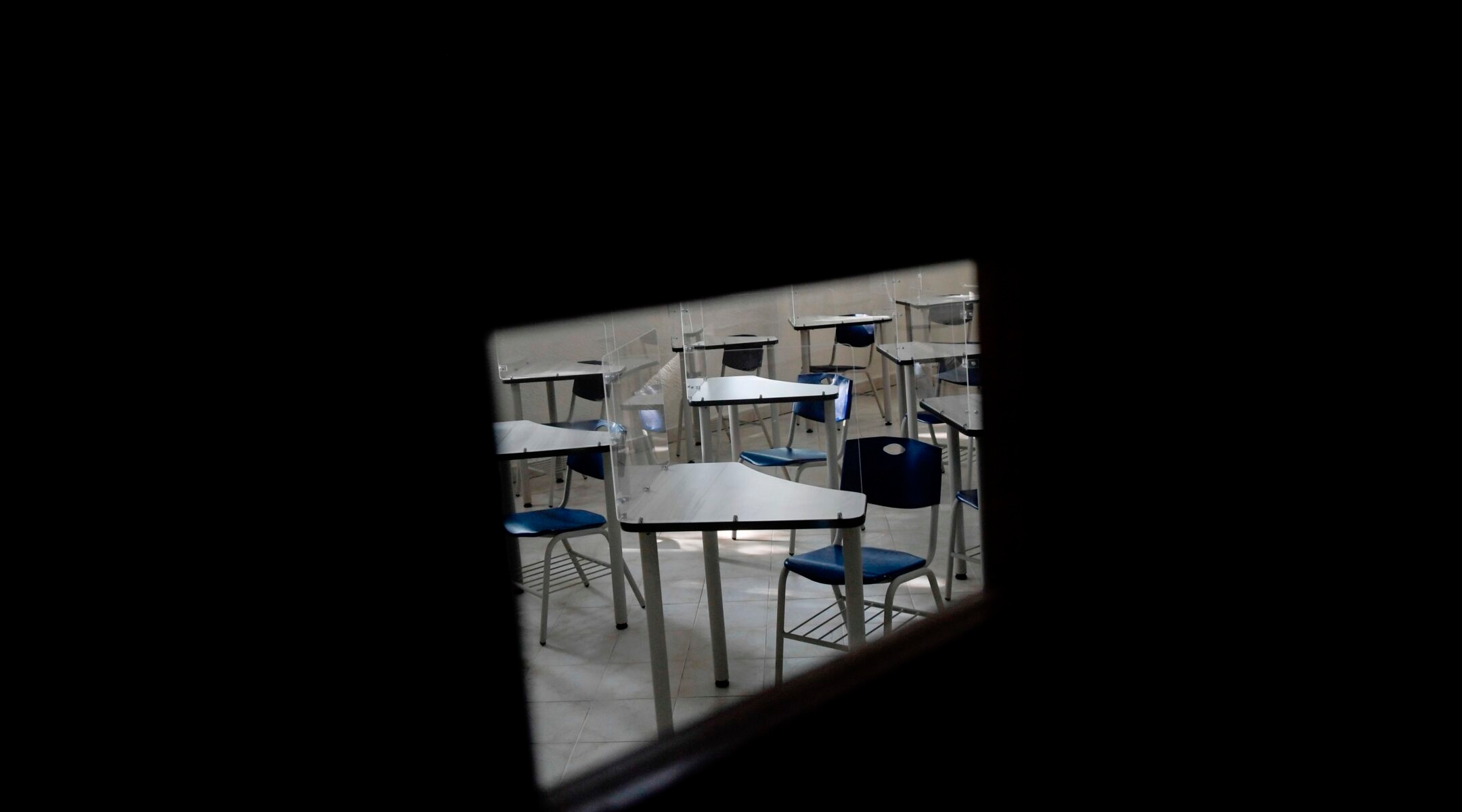

(JTA) — Since March, Jewish day schools have expanded their roles in the community to provide Jewish life and engagement 24/7. We have organized memorial services, supported families in financial duress and served important public health roles. We have done all this while launching an entirely new product overnight — full-time online learning.

Now we are planning to go back to school. This month, Jewish day school employees across the country from North Carolina to Los Angeles are preparing to return to in-person work in buildings filled with students and employees. Next month, schools in the New York Tri-state area, the region with the largest concentration of Jewish day schools in the country, plan to join them. We will be the first sector of the professional Jewish community to do this.

As a Jewish community, we have honored and supported our frontline workers — the senior living staff, clergy and others — during this pandemic. They all deserve deep appreciation and extra care for the risks they take on behalf of all of us.

Day school employees are about to become frontline workers, too. As people who are steering some of the Tri-state region’s 250-plus Jewish schools toward reopening, we are acutely aware of the risks that our employees are taking to return to school, and we want to demonstrate our care in every way we can.

But the decisions we are making and the expenses we are incurring are not things that each school should be handling on its own. Nor should they be solely the purview of the increasingly contracting realm of day school funders. Caring for our frontline workers is the responsibility of the Jewish community as a whole.

Together with a handful of local colleagues, we are spending at least $5 million on costs like facilities upgrades, additional space, ventilation upgrades, additional staffing and PPE, with the largest among our schools spending more than $1 million. With the costs continuing to mount and uncertainty about whether the plans we make today will be enough next month, the full tally of resources needed to make our schools safe is unclear. What is clear is that we cannot cover these on our own without cutting deeply into other priorities.

We recognize and appreciate that there are institutions trying to support us. National and local organizations have offered timely, thoughtful and effective professional development the whole way through this pandemic. Others have offered support and tools, such as tuition assistance for the most financially vulnerable students, the opportunity to purchase some PPE in bulk at slightly reduced prices or starting a listserv for the hundreds of school-specific COVID medical advisory committees to share ideas. A national consortium of funders initiated a grant and loan program to which day schools, among other institutions, could apply.

All of this is appreciated, but none of this is enough. Each individual school is still left to figure out how to “make it work” during the most confusing and volatile time of our generation.

This is the case for America’s 13,000 school districts, too. A coordinated response, with resources to support the unprecedented needs, would help all schools figure out ways to bring children back to school while keeping them and their teachers safe.

While a national response is not emerging, it is not too late for a more significant coordinated Jewish response. Already, we have examples to learn from, in the sort of efforts under way in a number of places, like both Bergen County and Metro West New Jersey, Boston and Toronto to name a few. In some areas, regional medical committees have been convened to lead all Jewish institutions through the labyrinth of COVID-related decision making, or money has been raised to support all regional schools in procuring PPE.

We need community-wide leadership. Here are four concrete opportunities for a national and regional leadership to make a real difference in the lives of our day school employees.

First, bring together the best epidemiologists, infectious disease specialists and pediatric experts to set best practices for our community. Each school has convened its own medical advisory committee. Each newly released guidelines from federal, state, city and industry group sources require significant review and analysis. They do not provide clarity on their own, and most definitely do not provide clarity when read together. They are also changing: In the last week, the federal, state and city guidelines were all revised, forcing us to rethink our planning once again. We need to know what to do to protect our staff and children, and these decisions should not be made school by school. We need to standardize policies and best practices for our community overall.

Second, make sure every school can procure and implement proper PPE, testing and HVAC/ventilation systems to protect our teachers and other employees to the level of best practices. Most importantly, pay for this. Many of us cannot even afford to purchase medical grade masks for all our teachers. Schools are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars, in some cases upwards of a million, each to address ventilation, replace furniture to comport with social distancing rules, procure PPE and hire the additional staff needed to implement all the changes. Without support, schools with fewer resources will have to sacrifice either safety or educational quality, while schools with more resources — those whose parents can pay higher tuition, or have a robust alumni base, or own their buildings instead of renting — may be able to afford both.

Third, support the wellness of our staff members — our community’s frontline workers. Our staff members are scared, exhausted and committed to learning whatever they need to in order to continue to serve each child, a herculean effort during these times. A great educator can teach through all sorts of personal upheaval, but a person cannot be a great educator unless they are inspired. Inspiration is hard to come by when you have “nothing left.” We need to offer real mental health services to all Jewish day school staff members. That means developing a system to support the emotional and spiritual wellness of Jewish day school leadership and educators and, again, having that system paid for.

Finally, please do not make us jump through hoops to access the extra funds we need to ensure that our day school students and teachers are safe and learning. Make grants easier to access, with quicker turnaround time, and a timeframe that actually works within the context of schools, which never have months to spare before putting programs and procedures into place.

There is little time to spare. Teachers — this critical demographic of Jewish communal frontline workers — are coming back to school next month. Our community needs to act now to ensure their safety and wellness.

Nora Anderson, Beth Am Day School

Stephanie Ives, Beit Rabban Day School

Danny Karpf, Rodeph Sholom School

Rabbi Dr. Jeffrey Kobrin and Ofier Sigal, North Shore Hebrew Academy

Rabbi Bini Krauss, SAR Academy

Rabbi Joshua Lookstein, Westchester Day School

Benjamin Mann, Schechter Manhattan

Rabbi Gary Menchel, Yeshiva Har Torah

Nicole Nash, Hannah Senesh Community Day School

Amanda Pogany, Luria Academy of Brooklyn

Deganit Ronen, Westchester Torah Academy

Sara Rosenfeld, Barkai Yeshivah

Rabbi Yahel Tsaidi, Yeshivah of Flatbush Elementary School

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.