(The New York Jewish Week via JTA) — The conversion of three hotels on the Upper West Side into temporary homeless shelters has divided the local Jewish community.

Rabbis and other area residents are lining up on both sides of a heated debate over the relocation of some 700 homeless individuals, which critics say has brought drug use, crime and vagrancy to the relatively affluent area.

“We are not NIMBY people,” said Rabbi Robert Levine of Congregation Rodeph Sholom, using the acronym for Not In My Backyard. “But the city can’t slip 700 homeless people into local hotels and expect the community not to notice.”

Supporters of the shelters, meanwhile, say the community needs to welcome the residents and show more compassion to the homeless during the coronavirus.

Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herrmann of SAJ, a pluralistic synagogue in the neighborhood, spearheaded efforts to deliver resources to the makeshift shelters. In a widely circulated letter, she implored community members to “learn more about the roots of homelessness and examine our own prejudices.”

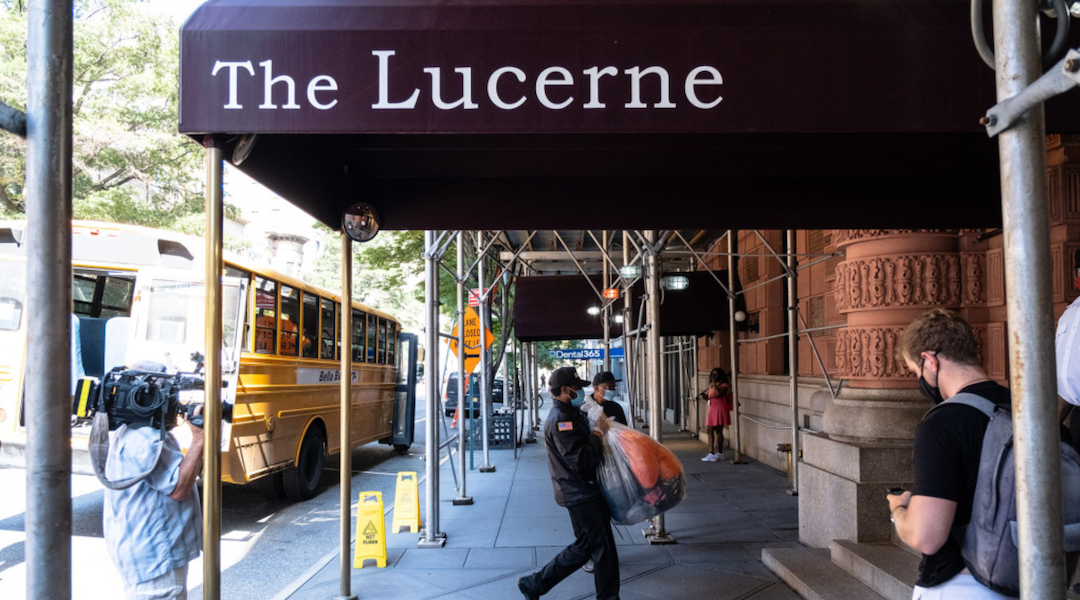

The three area hotels — the Belleclaire on Broadway, the Lucerne on 79th Street and the Belnord on 87th Street – were converted to house the homeless under a contract between FEMA and the city. Each is run by a separate nonprofit. Hotel rooms are necessary to protect the homeless from COVID-19, officials explain.

The community response — evident in opposing Facebook groups each with thousands of members, dueling petitions, and countless calls and Zoom meetings with local politicians — touches upon several lightning rod issues, including racism, safety, privilege and the interpretation of the Jewish edict to help the poor.

In Upper West Siders for Safer Streets, a private Facebook group that has amassed over 7,000 members over the course of days, local residents have been angrily sharing concerns.

“We are for homeless assistance & compassion but we are against registered sex offenders and drug use in our community,” the page description reads.

(Several registered sex offenders were among those housed originally at the Belleclaire and the Lucerne. In an Aug. 9 email, local City Council member Helen Rosenthal addressed the issue, saying she will be “hawkeyed about ensuring that laws regarding sex offenders’ residency, and proximity to schools and playgrounds, are being closely followed.”)

The Facebook group includes numerous photographs of homeless people, largely unmasked, sitting on street corners, injecting drugs and urinating in public.

“We’re not bigots if we want kids to be safe,” said Rabbi Levine, whose Reform synagogue has several thousand members. He criticized elected officials for the abrupt, nontransparent manner in which the new, purportedly temporary shelters were introduced.

Jewish residents of the Upper West Side have also been mainstays of the counter-effort to support the new homeless residents.

“We can come together around not harassing these people,” Rabbi Herrmann said. Snapping and sharing photos on social media of “unfortunate behavior” undermines a “compassionate approach,” she said.

Working alongside Herrmann, area resident Melissa Bender has been instrumental in creating a counter Facebook group and drafting a petition to support and advocate for the new homeless neighbors. (The petition, titled “Upper West Siders for a Compassionate, Safe and Equitable Community,” had 1,500 signatures as of Tuesday, compared to the nearly 6,000 signatures garnered by the petition demanding “safe and clean streets on the Upper West Side.”)

Bender, a mother and self-described “lifelong New Yorker” who lives on the Upper West Side with her family, sees the response to the new shelters as blatant evidence of racism. (Since May, Bender and her family have left their residence due to the constraints of the pandemic. They plan to return in September for the school year, she said.)

“The idea that we, as residents of the Upper West Side, have the right to admit or deny entry to other people is a racist and uninformed position,” she said.

Bender, a physician turned photojournalist and a congregant at SAJ, said her position is informed by Jewish values.

“Given what our Jewish community has dealt with over the last century, I have trouble understanding why we can’t be more moved to make our neighborhood a welcoming one,” she said. Bender criticized vocal members of the West Siders for Safer Streets group for “failing to see a connection between this type of reaction and the collective work we have to do against racism.”

Shachar Benjamin, a 28-year-old risk manager and resident of the neighborhood’s Moishe House, said the “reduction of what’s going on to ‘taking care of the poor or not taking care of the poor’ is simplistic and inaccurate.”

“We’ve been made to feel that if we don’t support what’s going on or if we even complain, we must hate poor people,” said Benjamin, a graduate of the Columbia/Jewish Theological Seminary joint-degree program. An active poster on the Safer Streets Facebook group, he was criticized for a recent post praising the international media attention the local controversy has received.

“All other considerations have been swept under the rug for the sake of virtue signaling,” he said, firing back at the Equitable Streets camp. “What about women’s safety? What about victims of sex crimes who don’t want to be in close proximity to sex offenders? What about the fact that many of these people are not wearing masks in the midst of a global health pandemic?”

Among the many Orthodox members of the Jewish West Side community, whispers about leaving the city for good are spreading like never before, according to several Orthodox rabbis who requested anonymity.

“After COVID-19, we’re already scared of people moving out of the Upper West Side,” one young rabbi of a large Orthodox congregation said.

“We’re being presented with an unhelpful and untrue binary: Either you support the new shelters or you’re dehumanizing the homeless,” said Rabbi Daniel Sherman of West Side Institutional Synagogue, a large Modern Orthodox congregation in the neighborhood attended by many young families. “Taking care of the poor, something we as Jews should all value, is being used as a straw man to avoid engaging in real debate and conversation regarding the safety of our community.”

Rosenthal, meanwhile, has said that the city has made “clear mistakes” in its communication with the neighborhood and local officials. In a recent update to constituents, the Council member said the city has committed to holding meetings with community leaders on a regular basis. She also noted that some of the complaints she has been receiving are not related to the shelters but to preexisting homeless encampments in three spots along Broadway.

She also assured residents that the hotel residents will return to the city’s “congregate” shelters when officials determine it is safe.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.