(JTA) — They hid revolvers in teddy bears and dynamite in their underwear. They learned how to make lethal Molotov cocktails and fling them at German supply trains. The girls with “Aryan” features who could pass as non-Jews flirted with Nazis – plying them with wine, whiskey and pastry before shooting them dead.

When the Nazis occupied their native Poland, Jewish women, some barely into their teens, joined the resistance and risked their young lives to sabotage the regime.

That crucial but often overlooked story of defiance and resistance is told by Judy Batalion in her new book, “The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos” (William Morrow). It’s the result of her 12-year odyssey digging through archives and interviewing descendants of the women. The research skills she honed while earning a doctorate in the history of art from the University of London helped her navigate the daunting challenges of crafting a cohesive, factually accurate narrative out of history shrouded in myth and neglect.

The book and a companion edition targeting 10- to 14-year-olds are both due out on April 6 in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day. Director Steven Spielberg has optioned the book for a motion picture and signed Batalion to co-write the screenplay.

“I was slow with this book because it was so challenging – emotionally, intellectually and practically. I had to deal with reading incredibly difficult memoirs and testimonies on my own,” she said in a phone interview from her New York City home.

Batalion, who spent her mid-20s in London working as an art historian by day and stand-up comedian at night, is not a Holocaust scholar accustomed to reading graphic primary sources. She felt weighed down by the women’s accounts of being sexually assaulted by Nazis, of soldiers stomping on Jewish babies and of mass murder committed before their eyes.

“Their stories seeped into my system. I worked on it in dribs and drabs when I could,” Batalion said of her years of off-again, on-again research and writing.

Niuta Teitelbaum as a schoolgirl in Łodź, 1936. During the war, she became known as “Little Wanda with the Braids.” (Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum Photo Archive)

Donald Trump’s election as president, with the misogyny and anti-Semitism that she saw churned up in its wake, pushed Batalion to go all in and craft the ghetto girls’ stories into a work of narrative nonfiction.

“I felt a shift in the zeitgeist. The importance of telling honest stories about women in the Holocaust and women’s empowerment felt urgent,” she said. “I dashed off a book proposal and committed to diving into two years of intensive, focused research.”

At the heart of the project is an obscure Yiddish book published in 1946 titled “Freuen in di Ghettos” (“Women in the Ghettos”) chronicling these young women’s tales of resistance and derring-do. Batalion discovered the dusty tome by chance in London’s British Library while researching strong Jewish women. Why, despite her years of education at a Montreal Jewish day school, where she learned Yiddish and Hebrew, and as the granddaughter of Polish Holocaust survivors, had she never heard of these ghetto girls?

“My research was very complex and strangely time consuming. I had to work in multiple languages,” she said. “The women’s names and the place names had so many confusing iterations — Yiddish, Polish, Hebrew, English.”

Her research missions took her to Poland for two weeks and Israel for 10 days. She visited the places that her heroines wrote and spoke about.

“I wanted to understand what the ride from Krakow to Warsaw looked like from the train window and experience a taste of what they did,” she said.

Batalion hit the research jackpot at Warsaw’s new Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews, where an archivist directed her to thousands of pages of information about Jewish resistance fighters. She snapped photos of the documents to share with a Polish translator in New York.

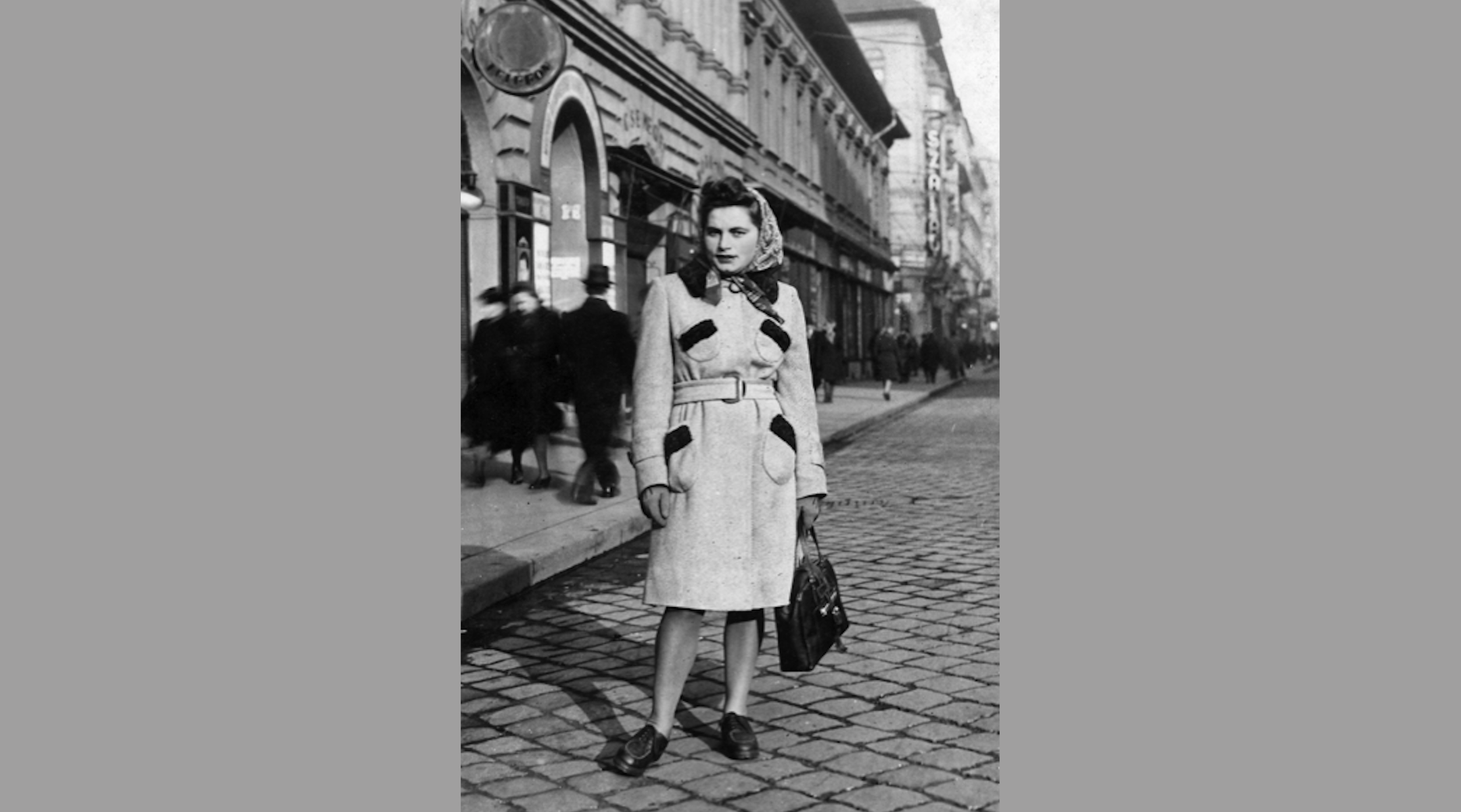

Renia Kukiełka in Budapest, 1944. (Courtesy of Merav Waldman)

“The Light of Days” highlights the incredible tenacity of Renia Kukielka, one of the youngest ghetto girls. As a 15-year-old, Renia saw her parents deported from the Będzin ghetto to Auschwitz. Fueled by outrage, she and her older sister, Sarah, joined the ghetto’s resistance movement.

Renia’s youthful charm, fluent Polish and soft features made her an ideal courier. The Jewish underground obtained expensive fake papers that established Renia’s identity as a Catholic Pole. She successfully ran multiple missions, smuggling weapons, correspondence and money from Będzin to Warsaw until the Gestapo discovered her papers were forged and threw her into prison. Despite repeated beatings that left her bloodied and unconscious, she clung to her cover story and never revealed her Jewish identity.

Sarah and her underground comrades bribed a guard with whiskey and cigarettes to rescue her from prison. Weak and feverish from starvation and physical abuse, Renia mustered the strength to run through forests and over snow-capped mountains. She survived a tortuous journey through hidden bunkers in Slovakia, then on to Hungary, Turkey and the ultimate destination – Palestine.

Against terrifying, oppressive odds, Renia lived to tell her story in a memoir she began writing at 19. When Batalion read Renia’s memoir she felt as if she’d discovered a kindred spirit – a thoughtful writer processing her experiences.

Batalion’s favorite research and writing involved the surviving ghetto girls’ postwar lives.

“I wanted to know how they reconstructed their lives after going through everything they did. I so wanted to talk to their children and find out who these women became,” she said.

She achieved this level of intimacy with her subjects on her trip to Israel, when she met with their descendants. Batalion was overjoyed to meet Renia’s adult children, who described their mother’s zest for family, fashion and world travel.

“This brought home on such a personal level that I was writing about real people,” she said.

Judy Batalion: “I was slow with this book because it was so challenging – emotionally, intellectually and practically.” (Beowulf Sheehan)

Batalion hopes the stories of female heroism she resurrected serve to inspire future generations of all faiths, especially her own two daughters, both in elementary school.

“These were women who saw and acknowledged the truth, had the courage to act on their convictions and fought with their lives for what was fair and right,” she said.

She feels a deep sense of connection to the ghetto girls who died fighting and believes they sacrificed themselves for the future dignity of the Jewish people. Their stories serve as a timeless call to action to women to empower themselves to resist all forms of oppression.

During this difficult COVID year, Batalion drew personal inspiration from her subjects’ life stories.

“Thinking back to their stories of courage and bravery really helped me,” she said. “I thought if they could get through the horrific challenges they faced, I can definitely get through this.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.