CHICAGO (JTA) — Just three stories high and hemmed into a small 5,000-square-foot lot, the building at 16 S. Clark St. is a small jewel box situated amid this city’s dense urban fabric. Exuding an aura of cool simplicity, the structure’s facade is composed of glass, metal and concrete planes. Its name is etched in delicate gold lettering: Chicago Loop Synagogue.

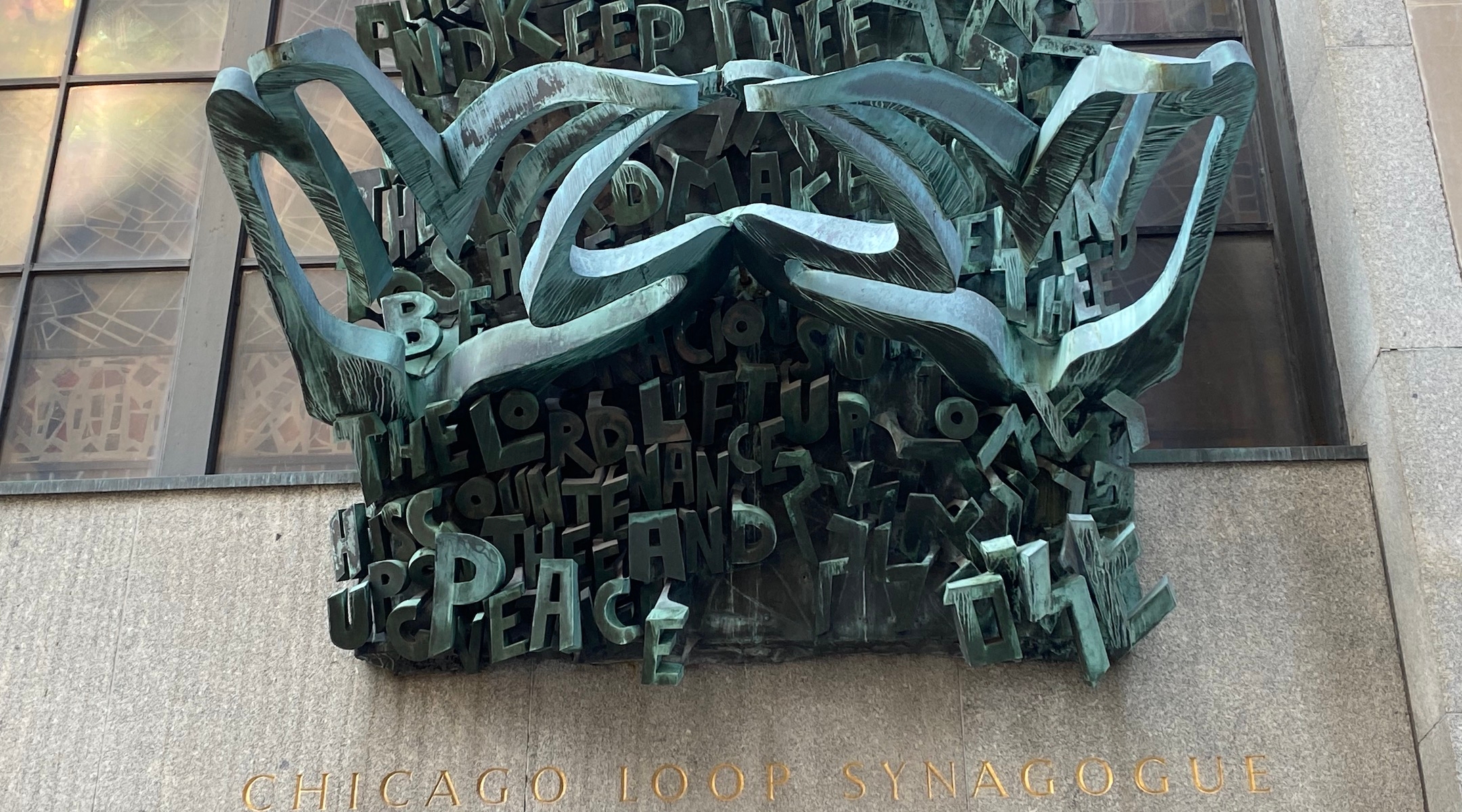

Perched above the synagogue’s front door, a two-ton sculpture extends over the sidewalk. Created by Henri Azaz in 1963, the work consists of bold letters tumbling over each other spelling the priestly benediction. A pair of massive hands emerges from the words, sloping downward as though placing a blessing on the heads of all those who enter.

The brass and bronze has since weathered and turned a tarnished green. Streaked with corrosive lines, the heavy hands now look weary. Chicago Loop Synagogue has fallen on hard times, and its future is precarious.

The only consistently operating Jewish house of worship in Chicago’s Loop, the 1.5-square-mile area touted as the second largest business district in North America, the Loop Synagogue has been unusual since it was conceived in 1929. Few members live anywhere nearby. Before the pandemic, most popped in for lunch or a prayer service during the workday while spending Shabbat at their home synagogues in the suburbs. In recognition of that unusual arrangement, dues top out at $180 — meaning that the congregation’s 400 members generate far too little revenue to keep operations afloat.

The pandemic abruptly halted the flow of commuters, severing ties that for many Loop members were only tenuous in the first place. But keeping the building closed also cut expenses necessary for operating the synagogue’s outdated and inefficient systems, buying the congregation’s leaders time to ponder the possibility of relocating to a less expensive space. One pressing question: What will happen to the historic stained-glass panels that are perhaps the Loop Synagogue’s most defining feature?

The congregation’s president, Lee Zoldan, reports that the synagogue has enough cash assets in the bank to continue running comfortably for another year and a half.

“Then we are headed for the red,” she said. “The time to panic is now.”

Chicago Loop Synagogue was initiated by a gift from the Midwest Branch of The United Synagogue of America (today the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism). The goal was to serve commuters seeking kosher food and a place to pray during the workday. It remains the only Loop venue to offer both services.

The institution quickly gained national recognition. By 1934, the prayer space was renovated to accommodate more worshippers, and was featured in the Chicago Tribune for installing air conditioning. Situated just a few blocks from the site of the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair, the synagogue also boasted wall paintings designed by A. Raymond Katz, official muralist for the “Century of Progress.”

Today the Chicago Loop Synagogue holds fast to its identity.

“We are not a neighborhood synagogue,” administrator Mary Lynn Pross said. “We have always been a synagogue for the world.”

Now, as in its early years, synagogue members include commuters from Chicago’s nearby suburbs. Les Blau is among them. Each weekday morning prior to the pandemic, Blau attended services at Central Avenue Synagogue, a Chabad-affiliated house of worship near his home in Highland Park, then hopped on the train for a 45-minute ride to his law office in the Loop. In the afternoons, Blau took a quick jaunt from his office to the Loop Synagogue to attend mincha, the afternoon service.

“It’s the only institution like it in the Loop – the only synagogue in the area that holds afternoon services every weekday all year round,” he said.

Other commuters come from New York, Los Angeles and internationally.

“We’ve got members who regularly fly in on business,” Pross said. “Whenever they are in town, they head here for daily services.”

The downside of serving as a destination synagogue is a weak sense of community. Nearly every member also belongs to a home synagogue closer to where they live.

“We are really three – or even four – different congregations,” Zoldan said.

Strong ties bind members who saw each other every day at shacharit, the morning service. So, too, for those who regularly attended mincha, like Blau. But the two groups generally didn’t overlap. Nor did they intersect with the 30 to 40 members who live in the Loop’s immediate outskirts and regularly attended services on Saturdays.

Decline began long before the synagogue shut its doors in response to COVID-19. Between 1992 and today, membership numbers dropped from 1,400 to 416. Zoldan offers a conjecture to explain why: “As our regulars retired and stopped attending, they were not replenished with newcomers.”

That appears unlikely to change. Some of those who attended services regularly before COVID-19 are being vaccinated and looking forward to returning to their luminous prayer space once the pandemic is under control. But pre-pandemic commuting patterns seem unlikely to resume. Meanwhile, new options are emerging to serve younger Jews who are moving to the West Loop, an adjacent and up-and-coming neighborhood.

That has put intense pressure on the Loop Synagogue, where leaders fear losing people if they raise dues significantly beyond $180 a year, a fraction of what full-service suburban synagogues charge members.

“We are in dire straits,” Pross said. Overall, operating expenses for the building run approximately $400,000 a year, and the synagogue has no endowment or large donors.

The “Hands of Peace” sculpture is mounted at the entrance to the Chicago Loop Synagogue. (Michael Landau)

Letting go of their mid-century modern structure, however, is hardly the ideal answer. Never mind that it is an architectural gem or that the congregation’s most significant asset – its property located just blocks west of Millennium Park – is worth millions. Relinquishing the building would also doom the fate of Chicago Loop Synagogue’s monumental stained-glass window.

Designed by the renowned New York-based artist Abraham Rattner especially for the synagogue, the work was the subject of a 1976 exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and a 1978 exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. Insured for $1.5 million, the spellbinding window is simply too large to fit anywhere except where it sits now: inside the prayer space for which it was created.

To create the work, Rattner drew inspiration from the opening passages of Genesis, honing in on the hidden meanings of the words “… and there was light” to channel cosmic creative energies of the Divine.

After two years working on conceptual and design schemes, Rattner spent another year engaged in the window’s fabrication in the Paris studio of stained-glass artist Jean Barillet (where other American synagogue stained glass has also been fabricated). The scale was expansive. At 40 feet wide and three stories high, it was devised to fill the entire eastern wall of the synagogue. Jutting into the prayer space from the far-left corner of the window, Rattner incorporated the ark that would house the Torah scrolls. He surrounded it with flames – integrated into the glass – leaping up and out, drawing attention to the presence of God in the very heart of the sanctuary.

Rattner once wrote that he wanted Chicago Loop Synagogue worshippers to experience “renewed faith in a higher elevation of being.”

“Rattner was a deeply spiritual artist, imbued with a powerful moral connection to his own Jewishness,” said Samantha Baskind, a historian of Jewish art at Cleveland State University.

Today the synagogue’s vast space, cathedral-like in its openness, is dominated by the window. A kaleidoscope of blues and purples pierced by electric shades of yellow take on the forms of planets, trees, Hebrew letters and the Israelite tribes hovering and extending toward one another. Those who enter are “awestruck,” Blau said. And Pross, who herself is not Jewish, recalls people dropping into the building before COVID-19.

“They came just to sit in the sanctuary. It’s hard to explain to someone who has not been here,” she said. “You have to be in that room, with the light streaming through that window … the experience transcends religious identity.”

In addition to these occasional visitors, over 2,000 people visit the space each year as part of the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s annual Open House tour. Groups from the Art Institute of Chicago and the Chicago Historical Society also regularly tour the building to study the architecture and behold the window.

Zoldan has convened a task force charged with imagining a new future for the congregation and its building: one that will generate revenue while allowing them to preserve the Rattner window intact and continue meeting in their space. Possibilities include identifying an organization to co-locate in the building, such as an education center, a theater or an event space.

The most desirable of the options on the table: create a national sanctuary for synagogue stained-glass. Envisioned in part as a light-and-color experience and in part as a museum, this “stained-glass sanctuary” would provide dissolving synagogues across the county safe haven at Chicago Loop Synagogue for their own colorful windows.

This idea is favored by task force member Michael Landau, an architect who has worked on over 75 U.S. synagogues and is known for his creative reuse of historic sacred materials. Landau takes windows, Torah arks, eternal lights and other treasured ritual objects that hold synagogues’ histories and incorporates them into new contemporary design schemes.

His goal with the objects is “honoring their history by giving them new life and provoking interest in their past.”

That is Landau’s hope for Chicago Loop Synagogue. As other congregations across the country shrink, disband and struggle to figure out what to do with their own stained glass, the Loop Synagogue with its Rattner window beckons.

“I think it can serve as a beacon,” Landau said, a gathering place for displaying the windows and telling the stories of their congregations.

Blau is likewise optimistic about the synagogue’s future.

“All it takes is one person – or a few — who don’t want to see this magnificent structure go to the wrecking ball,” he said.

Zoldan, the president, is more pensive.

“There is a lot of work to be done,” she said. “This is a monumental endeavor.”

In the worst-case scenario, the congregation would have to leave its building altogether. Fearing that possibility, Zoldan has reached out to a number of museums to see if she might find a new home for the window. But at three stories tall, the work’s tremendous scale would make moving it prohibitive.

“I don’t want to see it divided up into pieces and sold off as scrap,” Zoldan said, pausing and taking a deep breath before continuing.

“That window has been the centerpiece of our sanctuary since the day it was installed. We are attached to it,” she said. “The window, our location, our historic building — they are all integral to who we are.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.