(JTA) — Stephen Sondheim, the Jewish lyricist and composer who redefined the American musical through a monumental canon of influential and innovative theatrical works, has died at 91.

He died suddenly Friday after enjoying a Thanksgiving dinner with friends at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut, The New York Times reported.

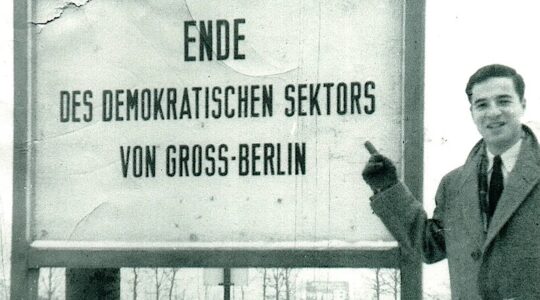

Sondheim’s stunning debut came writing the lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s score for “West Side Story” in 1957, at age 27. Sondheim was born to Jewish parents in New York City but raised without any formal Jewish background, to the extent that he once said Bernstein had to explain to him how to pronounce the words “Yom Kippur.”

Sondheim’s other well-known musicals include “Into the Woods,” “Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street,” “Follies,” “A Little Night Music” and “Sunday in the Park With George.” Many of them were not smash hits immediately, as he avoided traditional Broadway formulas that would immediately draw audiences. Instead, he crafted musicals that dealt with subjects that had not received treatments on mainstream stages: loneliness, despair and the artistic temperament.

There was the young man who is terrified of emotional commitment in “Company” (1970); the family torn apart by emotional dishonesty in “A Little Night Music” (1973); the vicious serial killer in “Sweeney Todd” (1979); and the artist in the midst of conceiving a masterpiece in “Sunday in the Park with George” (1984). “Into the Woods,” a mashup of characters from multiple fairy tales, won several Tony Awards in 1987.

Revivals staged years after often did better than original runs, but he is often cited as one of the 20th century’s most influential theater writers.

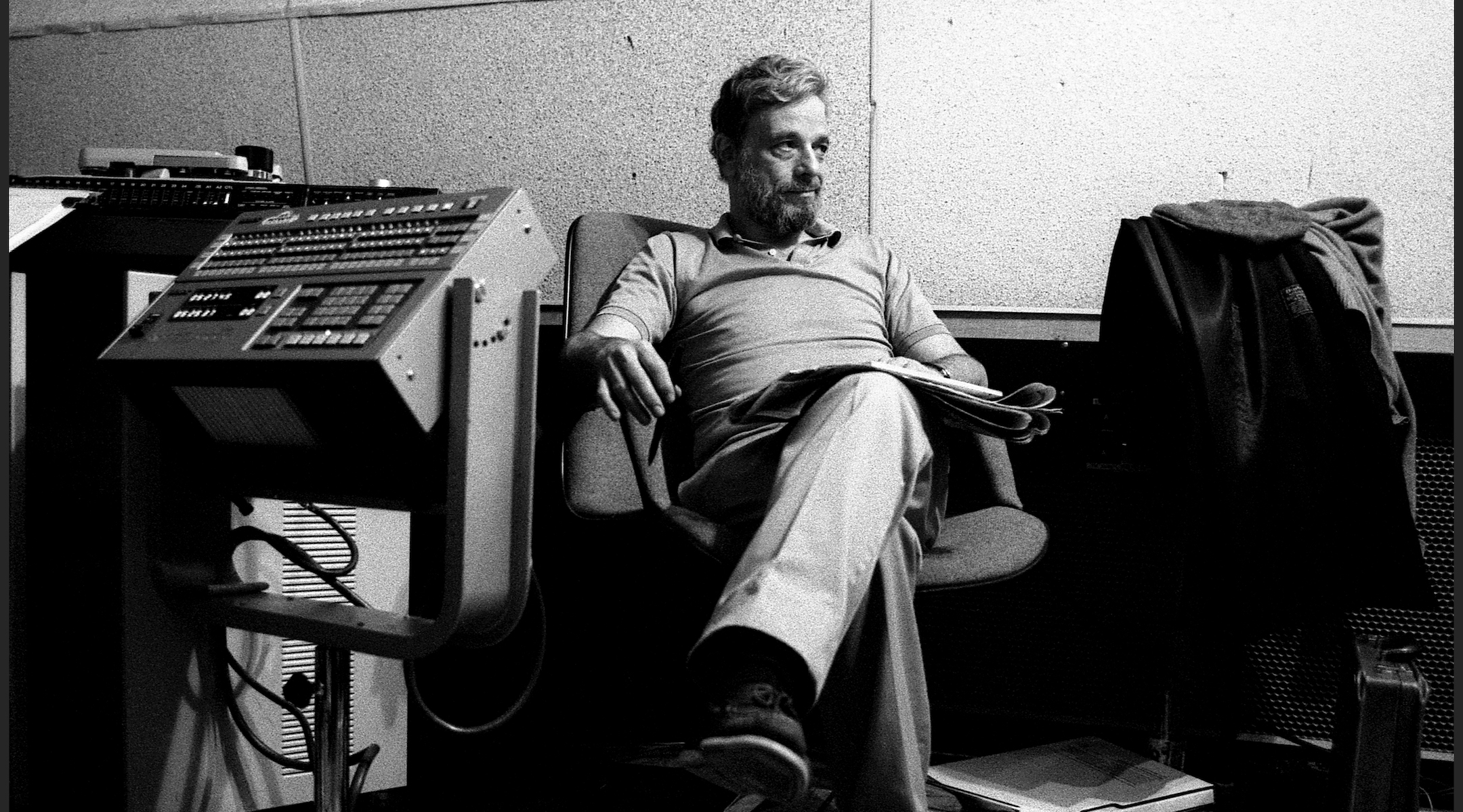

Stephen Sondheim, left, with Leonard Bernstein in 1973. (Ron Galella/Getty Images)

Sondheim — who did not entertain a romantic partnership until he was 60 — also often wrote about loneliness and whether the capacity to create a longterm relationship was possible. “Send In the Clowns,” a signature song from “A Little Night Music” that Frank Sinatra recorded a popular version of, remains a famous lamentation about bad timing when it comes to love.

“Isn’t it rich?” sings the character Desiree. “Are we a pair? Me here at last on the ground, You in mid-air?”

Sondheim hated when his fans and biographers attempted to examine his life to understand his music, but it was an irresistible enterprise. Born into a wealthy family in New York that ran a dressmaking company, his father left him and his mother when Sondheim was 10 years old, and his mother heaped on him hateful scorn, once telling him that her greatest regret was that he was born at all.

He found mentorship and a father figure in his teen years in a family friend, Oscar Hammerstein II, the lyricist of Jewish descent who had heralded an earlier revolution in the American musical, leading its transition in the 1920s from lighthearted reviews to novelistic treatments of major issues.

Hammerstein plotted out a four-step training for Sondheim while he was still in high school: Adapt a good play into a musical, adapt a flawed play into a musical, adapt a musical from another literary form, write your own musical.

Sondheim stuck assiduously to the course and at 22 began auditioning songs around New York. A producer, Lemuel Ayers, commissioned Sondheim to write songs for a musical he was producing, but Ayers died before it could be staged. Sondheim’s skills nonetheless became known in Broadway circles and at age 25, he was asked to come on board and write the lyrics for a musical Bernstein was planning based on “Romeo and Juliet.”

That became “West Side Story,” and Sondheim’s skill at weaving doom and despair into romance was immediately evident in the signature song, “Somewhere”: “There’s a place for us/ Somewhere a place for us/Peace and quiet and open air/Wait for us somewhere.”

Sondheim was a generous interview, speaking to journalists and even critics at length, and lacerating himself for years about lyrics he believed post-facto were misconceived. He hated that the big, emotive note in “Somewhere” was the “a” in “There’s a place for us.”

Sondheim earned multiple honors besides his many Tony’s, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015.

He settled into a comfortable elder statesman status late in life, traveling into New York this year to see revivals of his musicals, and living with his husband, Jeffrey Romley, whom he married in 2017 and who survives him.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.