This article originally appeared on Alma.

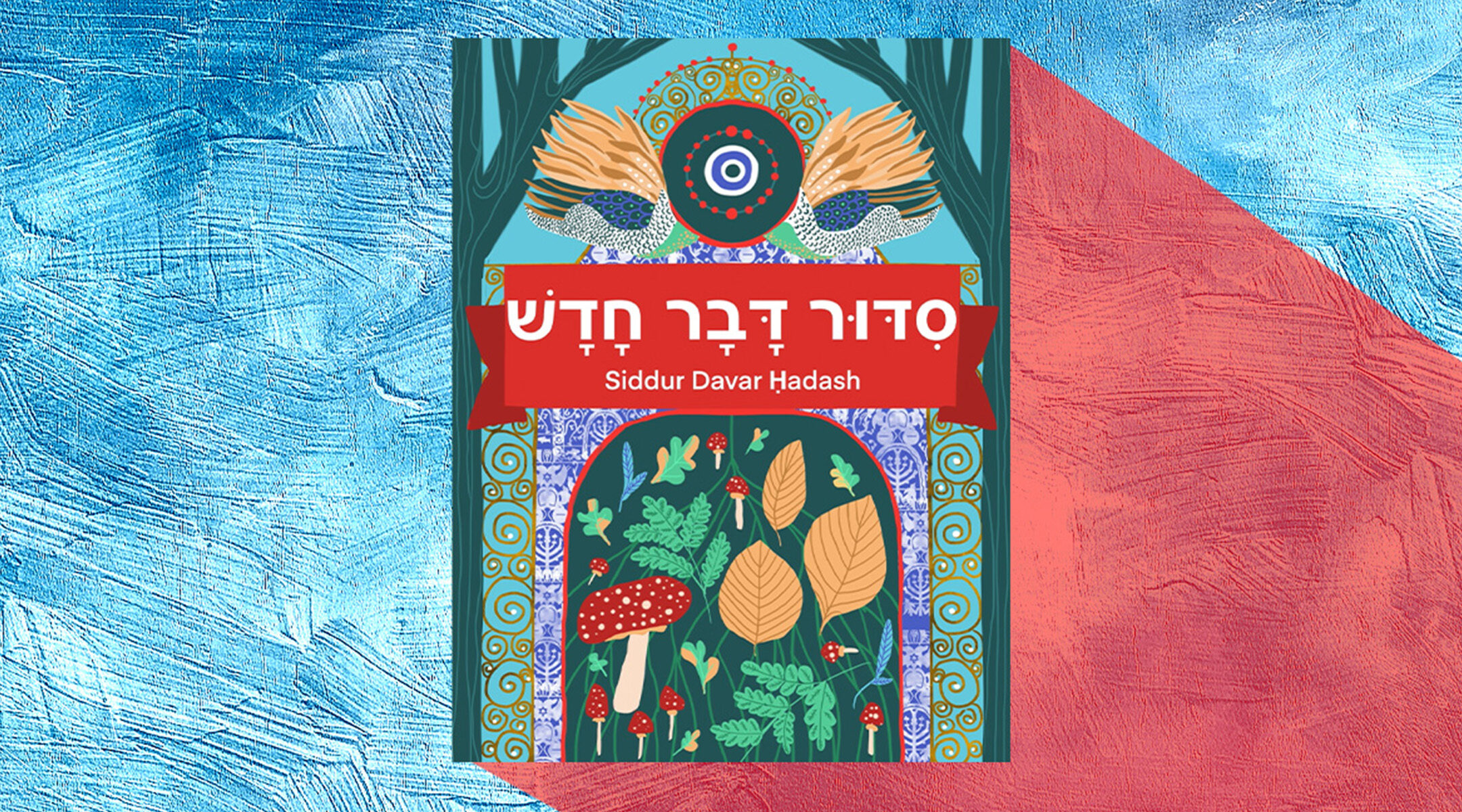

There’s a new siddur on the block that uses all nonbinary Hebrew forms and neopronouns for G-d* in English.

“Siddur Davar Ḥadash” is designed for accessibility, with full transliteration and full translation, via searchable PDF — or open-source text, which allows users to customize it.

The siddur was created by trans Jew brin solomon (it/its pronouns), whom I have had the pleasure of knowing for a few years. Neither of us can remember exactly how we met — perhaps at a trans-centered Shabbat service, or maybe while helping another trans Jewish friend move — but the world of trans Jews living in the same city is small, even when that city is New York, and many of us actively create queer Jewish content somehow find each other. (brin did ultimately include a poem of mine in the siddur.)

I spoke to brin about the process of making the siddur, how “Davar Ḥadash” is different from standard siddurim that people might be more familiar with and plans for what’s next.

This conversation has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Alma: What originally prompted you to start working on this siddur?

solomon: The seed came from being nonbinary, going to shul, and encountering grammatically masculine language in Hebrew. A trans cantorial student, Ze’evi Tovlev, came to my congregation and did blessings there based on the Nonbinary Hebrew Project. I was like, “Nonbinary Hebrew exists? Wonderful! Someone should make a siddur with this!”

Then the pandemic happened. I thought it would be cool to do services over Zoom with friends, but not all online siddurim were equally accessible. There were copyright restrictions and questions about doing denomination-specific services. So I thought, “Why don’t I use the Nonbinary Hebrew Project to make a siddur? It’ll take a couple months — why not?” What a naive child I was.

Then I thought, if I’m already changing language, it seems unkind to focus only on nonbinary inclusion; if I’m trying to imagine an inclusive Jewish liturgy, why not imagine the most inclusive shape I can?

How long did Davar Ḥadash take you?

There were three main stages. From July 2020 to October 2020 I learned the tools. I did a deep-dive in Biblical Hebrew grammar, how fonts for Biblical Hebrew work, how layouts work, etc. From October 2020 to March 2021 I did all the text, overhauling the Friday evening service from top to bottom. This included rewriting all the prayers and finding English reflection texts. Almost all the texts are public domain, because otherwise, putting paragraphs verbatim without commentary is legally dicey. But they’re not exclusively Jewish; other traditions have a lot of really deep wisdom that we can draw from. From March 2021 to release was sensitivity reading, copy editing and building the website.

You created a beautiful new set of neopronouns to refer to G-d in English. Can you talk about your thought process behind why and how you did so?

I’d repeatedly heard, “G-d’s pronouns are G-d.” I do believe G-d doesn’t have a human gender, so I tried using “G-d,” but I would get sentences in the Hebrew that would translate to English as “God is our G-d.” That’s tautological in a way it’s not in Hebrew.

There’s a theology that says you can’t have positive statements about G-d, just negative ones, because G-d defies human categories. Neopronouns exist in English partially to capture the idea of gender outside of traditional pronouns. I didn’t want to use any existing neopronouns, which might imply G-d’s gender is like that of people who use those pronouns — or that people who use those pronouns are more like G-d. Where G-d would have gender, there’s just a void. So I started with “Void” and looked at what else sounded good with that. I ended up with the set Voi/Void/Voix/Voidself, which all use the same vowel sound, and you pronounce the “x” in “Voix” like the final x in “onyx.”

Whom do you envision using this siddur? This could be in terms of gender, or at home versus in synagogues.

I designed it to leave some flexibility. My target audience was people who have felt excluded by the traditional language of prayer. I wanted it to be a gift to trans Jews, disabled Jews, and people from interfaith families, among many others. I want them to have a siddur to pray from where there’s room for them, that doesn’t say they’re inferior as humans or Jews.

You can use it on your own, but I’ve tried to leave it open-ended enough for a minyan too. You should also be able to follow along if you bring it to synagogue if you’re comfortable singing slightly different words. Which, I am, but I’m also obnoxious enough to do something like this, so I’m a bad yardstick.

It would be a real dream to have a synagogue print a bunch of PDFs or do a bulk order when physical copies are available and run an “Inclusive Siddur Project Minyan.” I’d love for it to inspire alternate versions, because there’s a limit to what one person can imagine. This isn’t the only way of doing this work, or objectively the best; it’s one form it could take. I hope people imagine others.

You’re also a composer; do you think people will be able to sing these new versions of the prayers to tunes they know? Do you envision people creating new tunes?

If people have tunes they love, mostly I think people should be able to sing them with no problem; some lines are tricky and the scansion gets funky. Sorry. I chose theology over scansion.

But I would love to see new tunes. There are a number of spectacular trans Jewish composers out there and it would be a wonderful opportunity to commission new liturgical music. Park Avenue Synagogue used to have a program to commission composers to write liturgical music; it would be beautiful and profound to have trans composers write new music with these new texts.

Do you personally use this liturgy?

Yes, I do, every Shabbos. While making it, I’d pray with as much as I had and then switch over. Each week, I’d get further before switching.

Which parts of making the siddur did you find particularly challenging?

One thing was technical support for writing in Hebrew with vowels and cantillation marks. Not many fonts can handle the necessary symbols or work on every operating system. Then programs expect you to write left-to-right, text size for Hebrew is often too small to see vowels, and when a program underlines something with a red squiggle, the squiggle obliterates everything. That was extremely frustrating.

Finding public domain passages for study was also frustrating because it took so much time. It was so open-ended, and due to COVID, I couldn’t just ask a librarian in person or go browse the stacks. A lot of public domain things aren’t online or are in non-searchable scanned images. Then there’s the problem of “this person was a really cool labor activist, but also hard-core eugenicist” or “this feminist was also super racist” or “this cool speech-maker was illiterate” or “they wrote things and weren’t white men so they weren’t preserved” or their papers were in a faraway inaccessible archive.

One petty thing, also: Anytime a piyyut rhymed and I had to change it but wanted to keep the rhyme scheme, that was a nightmare. I couldn’t find a Hebrew rhyming dictionary; I don’t know if one exists. Where I made changes for rhyme, I’m so sorry. Those are rough.

Looking ahead, I’m already stressed about the “Song of the Sea” and the psalm in Hallel about people who worship idols and how they’ll become like those idols — it’s about disability as punishment, which, yikes. It’s tricky both conceptually and because they’re poetry, so there’s not many syllables to work with.

Currently, Davar Ḥadash is freely available online. Can you talk about your hopes for the siddur’s future, and the timelines you’re looking at?

We’ve gotten feedback about making the website more accessible to people with visual disabilities, so short-term we’re tackling that. Then in January, we’re working on the full volume one. I hope to have a working draft by the end of 2022 to send to sensitivity readers and copyeditors, but that’s a long process. Hopefully, it’ll be shippable via print-on-demand in early 2023, but I’m more invested in doing it right than quick. After that, subsequent volumes will be:

2. A weekday book, hopefully by end of 2023,

3: Print-at-home bentsher, also in 2023,

4 & 5: Machzors for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (I might team up with someone for these),

6: Tisha B’Av,

7: Haggadah,

8: Chumash. That’s the capstone, so don’t hold your breath. It’d have the Masoretic text and an all-new translation of the Torah that takes trans and disabled readings seriously. That commentary exists; what if we had the courage of our convictions and translated it that way? And it’d include language play; the Torah is obsessed with puns and most translators have shied away from that or sequestered it in footnotes because it’s felt unserious, but for me, a beautiful and profound thing about language is when it surprises us with unexpected connections. We’d also have two essays for each Torah portion: one with historical/literary context, one with contemporary drash from different people who have been historically marginalized. If there’s budget, we’d also have a similar contemporary drash alongside the haftarah.

Then I will take a nap.

How does Davar Ḥadash fit into your hopes for the Jewish future?

I want to start at an unexpected and perhaps controversial place. I recently read the Conservative movement’s rulings about intermarriage and children of interfaith families. Many of those decisions seemed to stem from a fear that if children weren’t born to two Jewish parents, they wouldn’t choose to keep doing Judaism. If they had other options, why would they be Jewish? Perhaps it’s naive or the convert in me, but it seems to me that isn’t a very compelling way to conceptualize Judaism. It isn’t why I converted to Judaism or what motivates Jews I know.

Tradition is important to me, but when figuring how to get another generation to continue doing Judaism, my answer is to build a vibrant Judaism that has important things to say about the pressing issues of the day, has meaningful things for people dealing with a world full of stress, struggle, trauma and violence, offers meaningful solidarity, and takes real action towards a better world. If you can build that, people will want to be a part of it. Though I think it’s harder, that feels much more sustainable long-term to ensure a good continuing Jewish future. In imagining different liturgy, I hope this siddur helps imagine that Judaism.

Is there anything else you want people to know?

I’m very proud of the translation of “Lecheh Dodeti” which is singable and keeps the rhyme scheme, acrostic and the same middle word. Sometimes siddurim have a footnote that there’s something cool in the Hebrew, but it’s not in the translation. Give people who don’t know Hebrew the juicy stuff too! Is it cheesy? Yes! So is the Hebrew. The cheese is also holy. Lean into it.

*Judaism has a long tradition of being careful with writing the name of G-d — to prevent it from being accidentally discarded or defaced, the name of G-d in Hebrew is often abbreviated. Some Jews also extend this to English. Practices differ and Alma generally does not hyphenate “G-d” in English. However, it’s brin’s practice to write “G-d” with a hyphen, which is what’s used in “Siddur Davar Ḥadash,” and we wanted to honor the intentional choices being made regarding referring to G-d and marginalized Jews.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.