(JTA) — Felice Jacobs and Alan Feldstein could have tied the knot in Phoenix, where they met and where his mother worked at the local Reform synagogue. Or they could have held their wedding on the U.S. Army base in Austria where Alan was stationed at the time.

Instead, they chose the Eagle’s Nest, the Nazis’ former mountain retreat in the Bavarian Alps — a location that, as far as anyone knew, had never before hosted a Jewish wedding.

“We got married there because my husband wanted to thumb his nose at Hitler,” Felice Feldstein recalled last week.

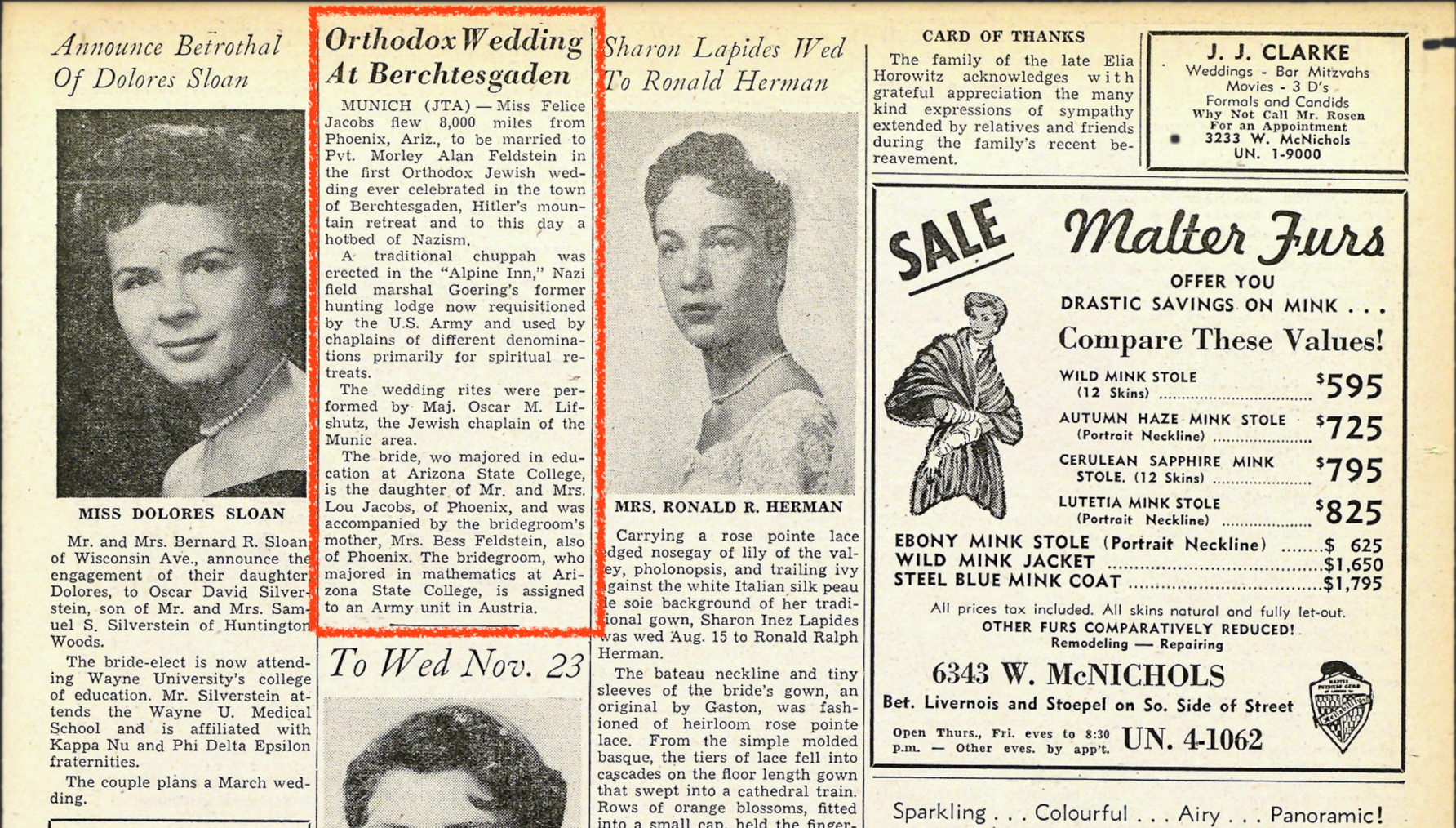

Taking place just 10 years after Hitler’s defeat and death, the Feldsteins’ August 1955 nuptials were so notable that the Jewish Telegraphic Agency covered them at the time, identifying the event as “the first Orthodox Jewish wedding celebrated in the town of Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s mountain retreat and to this day a hotbed of Nazism.”

It was not the last time that Alan Feldstein, who died last month at 88, would take a stand.

As a new faculty member at the University of Virginia in 1968, Feldstein once arrived home with only half a haircut — the result of an impromptu, one-man walkout after he learned that the barber shop wouldn’t serve Black customers.

The announcement of Felice and Alan Feldstein’s historic wedding appeared in newspapers that carried Jewish Telegraphic Agency stories, such as the Detroit Jewish News. (DJN archive)

After working at Los Alamos National Laboratory after returning from Europe, Feldstein earned a PhD in math from the University of California, Los Angeles. He then embarked on an academic career, first teaching at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. When a colleague decamped for Charlottesville, Feldstein set about convincing his wife to head south, too.

Felice was skeptical. Tension over race relations in the South was high: Charlottesville had only recently desegregated its schools after an extended fight; Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated the spring before their move. Alan soothed her anxiety by showing her a newspaper from his visit featuring a centerfold declaration in support of racial integration, signed by hundreds of local residents.

“That was enough for me to say, ‘we’re moving to a liberal town. We’ll be OK,’” she recalled.

The revelation about the barber shop came as a shock. But Feldstein did more than walk out. He went to the dean, who he knew also got his hair cut there, to press him to join a boycott.

Get more stories like this. Sign up for JTA’s Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREThe petition was not well received. “That’s the trouble with you outsiders coming in here and telling us what to do,” the dean told Alan, according to notes he took at the time.

For Alan, “outsiders” clearly meant Jews — which only served to galvanize him further. Ultimately, a boycott of segregated barbers supported by the University of Virginia’s student government caused many of the shops to agree to serve Black customers.

The victory would be an enduring point of pride for the Feldsteins — but in some ways it was short-lived. Alan’s contract was not renewed, which their son Mark said everyone understood to be retaliation. The family left Charlottesville, and Alan returned to his alma mater, Arizona State University, where he taught for the rest of his career.

Mark Feldstein said his father’s activism inspired his own: In junior high, he conducted an expose on the racist textbooks being used in the classroom. It also jump-started his own career in journalism. Mark is now the chair of broadcast journalism at the University of Maryland, after an extensive career in investigative reporting.

For the family, the wedding at the Eagle’s Nest was a foundational story. “Their getting married at Berchtesgaden in the aftermath of World War II was legendary,” Mark said. “And we were all very proud of that.”

American troops were occupying Berchtesgaden at the time, but the vast underground bunkers built for the Nazis had already been turned into a tourist destination.

Workmen pile rubble after dismantling the former luxurious home of Hermann Goering (right) on Obbersalzberg Mountain shortly after World War II. (Getty Images)

Felice didn’t take the tours. She was focused on the brass tacks of executing a marriage in another country, which included a civil wedding in nearby Salzburg in addition to the religious ceremony at the Alpine Inn, which sat atop a tunnel in which the Nazi leader Hermann Goering’s collection of looted art was found after the war.

At the Alpine Inn, the couple were married under a chuppah, the traditional Jewish wedding canopy. The rabbi was Oscar Lifschutz, a U.S. Army colonel whose long and storied military career included escorting the remains of Zionist leader Theodor Herzl from his grave in Vienna to a new burial site in Israel in 1949.

Afterwards, Felice recalled, the couple dined in a “lovely, lovely room” and stayed the night — running up a total bill of $125, or about $1,300 today. About 10 of Alan’s Army friends were present for the wedding, along with his mother.

“This wasn’t that long after World War II ended, and I think he and my mom both felt like this was not just a middle finger extended to Hitler but also a kind of affirmation of Jewish survival in the face of the attempt to extinguish our people,” Mark Feldstein said.

Among the ghastly toll were members of the Feldsteins’ extended families. Alan was with his grandfather when word arrived about the murder of someone in their family; Mark said he learned that their family came from a shtetl that was just across a river from a concentration camp. “No Jews made it through, including our family,” he said.

Felice recalled, “My grandmother’s sister, and her husband and family were annihilated. I have a family picture of that family. They were, I guess, wealthy Jews and they moved to Berlin. And that was the end of them.”

The extended Feldstein family, including Alan and Felice at the bottom right, in an undated photograph. (Courtesy Mark Feldstein)

Over the following decade, the couple would engage in another act of defiance: producing four Jewish children. After Mark came three girls — Rachel, Suzie and Sarah.

According to family lore, Mark Feldstein recalled, his father’s mother was critical when the couple announced their third pregnancy. She asked why they were having so many children.

“Well, Hitler murdered 6 million,” his father responded. “She shot back, ‘You don’t have to make up for all of them, do you?’”

Felice said her four children made sure that she and her husband of 66 years were never alone in the final months of his life.

“I am the luckiest person in the world,” she said.

Ill health in the last years of his life meant that Alan Feldstein didn’t speak to his family in detail about the deadly 2017 white-supremacist march in Charlottesville that saw neo-Nazis marching past the Reform synagogue where Mark Feldstein studied for his bar mitzvah.

Nor did he talk to them about Madison Cawthorn, the North Carolina Republican congressional candidate whose 2017 trip to the Eagle’s Nest propelled the Feldsteins’ wedding site back into public view in August 2020.

But his family knew that he was distressed by the hard-right turn that the United States appeared to be taking when Donald Trump was elected president in 2016.

“He saw parallels with what happened in Germany in the 1930s,” Mark Feldstein said. “The rise of authoritarianism, the promotion of racism — he was troubled by it, really troubled by it.”

Alan Feldstein died Jan. 29 and was buried in a private service on Jan. 31. The family urged mourners to direct donations to their synagogue in Arizona, Temple Emanuel of Tempe. Then, last week, the temple sent an email to community members: Someone had vandalized synagogue property, including by drawing swastikas on its trash cans.

“Does it almost feel like you came full circle from Berchtesgaden there to what’s happening here?” Mark Feldstein asked his mother.

“Well, that’s an angle,” Felice Feldstein said. “Of course [Alan] didn’t know what happened last week at the temple, but I can imagine how upsetting this would have been to him.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.