(JTA) — Philip Roth’s character Alexander Portnoy captured the insecurity of second-generation immigrants in two priceless sentences.

“I was asked by the teacher one day to identify a picture of what I knew perfectly well my mother referred to as a ‘spatula,’” Portnoy complains. “But for the life of me I could not think of the word in English.”

The joke is about a child of immigrants whose parents mix vocabulary from the Old Country into their everyday English, and pity the kid who has to figure out which is which. My parents weren’t immigrants, but I feel his pain. When I was growing up the few Yiddish words that sprinkled their vocabulary had essentially entered the English dictionary. I developed my “Jewish” vocabulary later in life, after time spent in Israel, classrooms, synagogues and in a series of Jewish workspaces.

I’m Portnoy with a difference: I know which words are Yiddish and Hebrew, but I can’t think of the words in English that do as good a job.

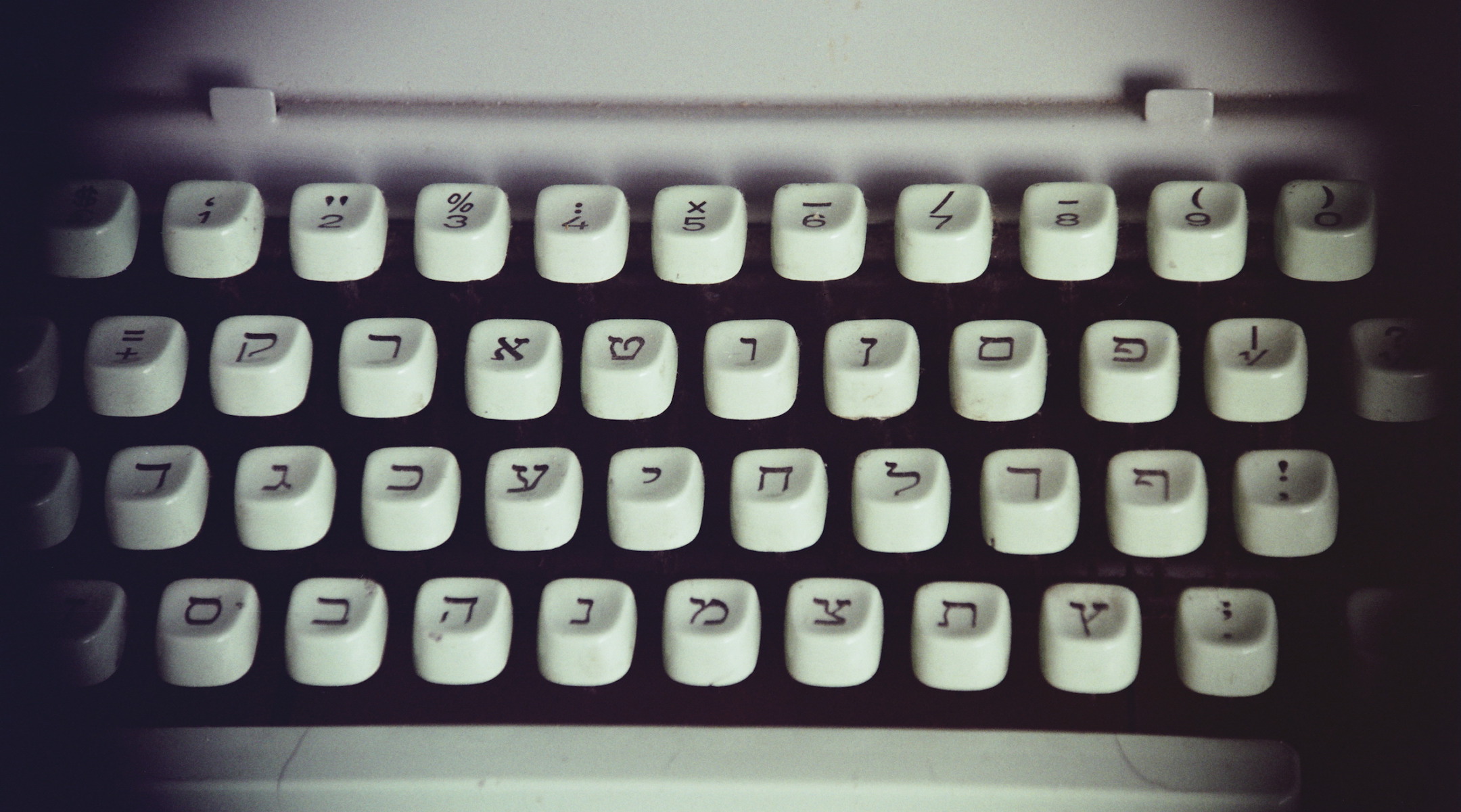

This comes up in my work at a Jewish media company. Journalism has its own specialized vocabulary, with talk of “ledes” and “nut grafs,” “sigs” and “kickers.” But there are also Jewish words for which there are no satisfactory substitutes in the newsroom.

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREConsider “nafke minah,” a Talmudic phrase that means something like, “What is the practical difference?” It’s a useful tool for examining in what ways the thing you are writing about is fresh or different from some other thing, or if it advances a developing story. It’s a close cousin of “hiddush” (or “chidush,“ not to be confused with kiddush), Hebrew for a fresh insight. If something doesn’t pass the nafke minah or hiddush test, it may not be news.

Similarly, “tachlis” (“tachlit” in Modern Hebrew) is indispensable in describing the main or operative point of something. Think of “brass tacks” or “bottom line” in English. I want to use the word whenever I am reading a story with a meandering opening and am restless to get to the main point, or if I suspect a source is dancing around a subject. It’s the difference between an organization saying “it is our goal to actualize new modalities for young Jews to engage in lasting relationships” and “we are a dating app.”

“Pshat” (rhymes with spot) is the plain meaning of something, stripped of “drash” (rhymes with “wash”), or interpretation. It’s essentially the who, what, where and when without the why. Reporters can be itchy to get to the interpretation of a news event; editors can be cranky in demanding that they first stick to the facts. Just give me the pshat. (Not that I am allergic to drash: It is also the role of journalists to interpret an event or phenomenon for the reader, once they have lined up the facts.)

“Nisht ahin nisht aher” is a Yiddish phrase my father used, meaning “neither here nor there,” or maybe, “neither fish nor fowl.” To me it describes a piece of writing that doesn’t know yet what it wants to be. Is this a profile of a bagel-maker or a story about the inexplicable popularity of the cinnamon raisin variety?

I polled my colleagues for the Jewish vocabulary they either use only in Jewish settings, or wish they could use outside the bubble. There were the untranslatable usual suspects like “davka” and “mamash” and “stam” and that Swiss Army knife of interjections, “nu.”

Which is not to suggest that my colleagues share a vocabulary or frames of reference, Jewish or otherwise. Hebrew Union College’s Sarah Bunin Benor studies the language of contemporary American Jews and has written about the ways their vocabulary tracks with their Jewish biographies: the older Jews steeped in Yiddishisms, younger Jews who have brought more Hebrew into the Jewish-English vocabulary, devout Jews who speak a Hebrew/Yiddish/Aramaic patois known as Yeshivish. There are proud Jews who have very little “Jewish” in their language and “insiders,” like me, who slip in and out of different Jewish skins depending on their audience.

And Benor’s latest project, tracking historical and living Jewish languages, demonstrates the linguistic diversity of the Jews beyond Ashkenazi Europe. (Benor’s side project, the indispensable Jewish-English Lexicon, introduced me to the Ladino gesundheit: “Bivas, kreskas, enfloreskas!” [“Live, grow, thrive!”])

Because of that variety of experiences and influences, I am hesitant to inflict my Jewish vocabulary on my colleagues – or, for that matter, on our readers. It is a challenge for anyone working in ethnic or specialized media: How much jargon do you use? In our case, do we use or need to explain words like shul, shiva, haredi or havurah? Is too much untranslated and unexplained specialty language just one more barrier to readers accessing not just our Jewish news sites but Jewish life as a whole?

Or, if you get too “explainy,” do you sacrifice your own credibility – and perhaps come off as patronizing to your readers?

The trick is hitting on a vocabulary that flatters the intelligence of readers without leaving them behind or on the outside — which, I might add, should probably be the guiding principle of any journalism enterprise, and any Jewish organization or institution, that wants to remain relevant.

Otherwise, bishvil ma litroakh?

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.