(JTA) — At the start of the 20th century, Louis Blaustein, a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania, and his son Jacob drove a horse-drawn wagon through the streets of Baltimore, selling coal oil and kerosene to grocery stores. They eventually grew the business into an oil company that is credited with inventions such as the metered gas pump, the drive-in gas station and the gas tank delivery truck.

Today, more than 100 years later, the descendants of Louis and Jacob are using a fortune built on fossil fuels to fund, among other causes, climate justice and environmental groups.

The various branches of the family have set up separate charitable foundations but they work together through the Blaustein Philanthropic Group, whose mission statement says the family is “united by roots in Jewish tradition, concern for social justice and equality of opportunity.”

Some branches donate to the major green organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund and to groups focused on local organizing like West Harlem Environmental Action and Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

And some of the Blaustein money is going to support explicitly Jewish climate activism. They have donated more than $300,000 since 2019 to Hazon, a long-standing environmental group, and Dayenu, a newer initiative created to bolster Jewish representation in the climate movement.

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn, the founder and CEO of Dayenu, said she’s grateful for the “critical and generous support” of the Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation, and she added that the giving has special meaning because of the origins of the family’s wealth.

“When foundations like the Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Foundation give to an organization like Dayenu that fights the fossil fuel industry in order to build a more just and sustainable future, it feels like a kind of teshuva,” she said, referring to a Jewish concept of making amends. “It feels like a reckoning with the source of their wealth.”

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREJewish wealth might not typically be associated with oil and gas, but the Blausteins are among at least a dozen major Jewish family dynasties whose fortunes come from the industry.

These Jewish fossil fuel dynasties vary by size — from multi-million to multi-billion dollar fortunes — and by their level of engagement with communal Jewish life. Some, including the Tulsa-based Schustermans, donate heavily to Jewish causes, and others, like the fellow Tulsans at the George Kaiser Family Foundation, give generously to charity but focus on secular initiatives.

For some family foundations, like the Max M. & Marjorie S. Fisher Foundation, which is a major donor in the Jewish world, oil is but a legacy — the source of the fortune but not a current business concern of the family.

Then, there are the Jewish philanthropists with current links to oil and gas. Stacy Schusterman, a major Democratic donor, helms both her family’s philanthropic foundation and the new incarnation of the family’s drilling company, called Samson Energy. Julie Beren Platt, who serves as chair of the board of trustees of the Jewish Federations of North America, is part of the family that founded and runs Berexco, an oil company based in Kansas.

The dynasties also differ in their approach to the climate crisis. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency sought to explore attitudes on the issue among oil and gas heirs currently involved in foundations that donate to Jewish causes, but nearly all the heirs declined to be interviewed. This reticence means the public can only catch a glimpse into boardroom thinking through rare public statements and the track record of grant-making by these foundations.

In some cases, the heirs appear to feel a responsibility to address the impact of fossil fuel emissions on the planets, while for others, it’s hard to tell. None appear to be outright climate change deniers.

The Blausteins, who donate to Dayenu and Hazon, declined to comment for this story. Another branch of the family, which gives to other, non-Jewish climate efforts, provided some insight into how it thinks about their responsibility as philanthropists.

Jeannie Blaustein, writing on behalf of the trustees of The Morton K. and Jane Blaustein Foundation, said her concern over the climate crisis does not stem from feelings of guilt.

“The origins of our family’s wealth sensitize us to these issues, but I strongly believe — and I think other trustees would agree with me — that we would have the exact same commitment without any personal relationship to the oil industry,” she wrote.

She also said she doesn’t see her philanthropy as a rejection of her ancestors’ legacy.

“Our commitment to climate change is a continuation of the lived values of our parents and grandparents, values born not out of guilt or shame, but out of respect for the dignity of human beings,” she wrote.

The environmentalism of the Blausteins casts them as a smaller, Jewish version of the Rockefellers. It was John D. Rockefeller who established Standard Oil, creating one of the biggest fortunes the world has ever known and prompting the U.S. government to intervene and force the company to break itself up into several pieces, including one known today as ExxonMobil. The current generation of Rockefellers is busy fighting ExxonMobil, using the family’s inherited wealth to undo our planet’s dependence on fossil fuels.

A fresh reminder of the price of allowing unlimited greenhouse gas emissions was supplied last week by a deadly heat wave in Europe. It came right as Sen. Joe Manchin sunk the Biden administration’s climate legislation.

Rosenn, of Dayenu, pinned the blame for the legislation’s failure on lobbying by the fossil fuel industry and vowed to keep fighting. She cited biblical Moses and David as inspiration, echoing the group’s message that Jews, while small in numbers, have an important role to play in the climate movement.

With the ascendance of oil at the turn of the 20th century in the United States, Jews tended to occupy the lowest rungs of the industry. A common story tells of the Jewish entrepreneur who salvaged decommissioned pipes and old well field equipment and sold them for scrap. These were often recent immigrants who had left Eastern Europe in search of economic opportunity.

Throughout the South, they established communities, building houses of worship and other communal institutions. Over time, they moved from the scrappy margin of the industry to its center: the discovery and production of oil.

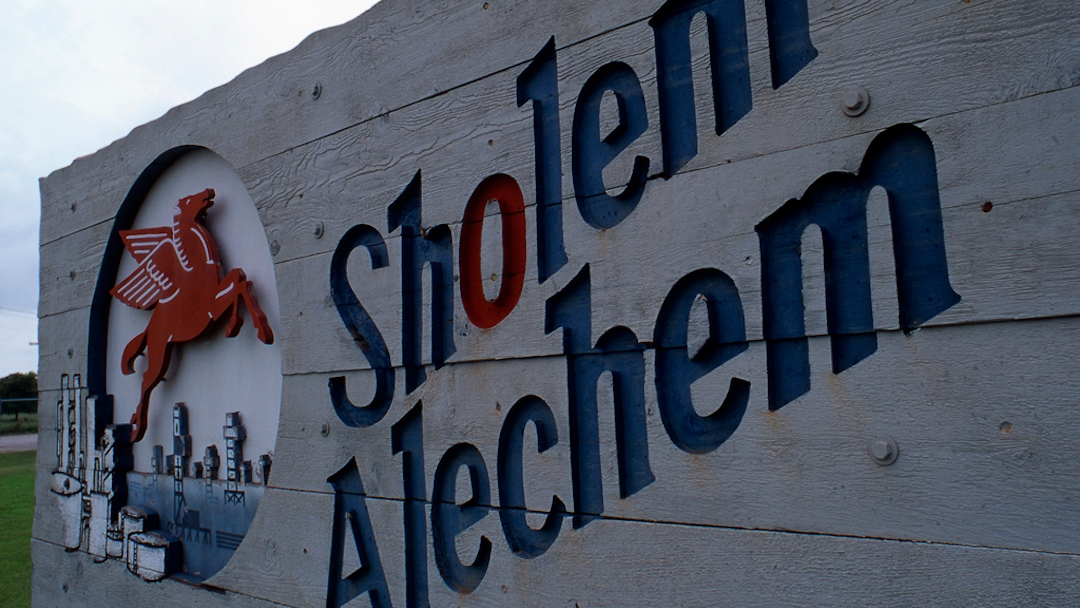

Jews and the Yiddish they spoke were common enough in the early 1920s that the local newspaper in the town of Ardmore, Oklahoma, explained the meaning of the customary greeting “sholem alechem.” That phrase became the name of a local oil fraternity as well an oil field that is still producing to this day.

A sign shows the entrance of the Sholem Alechem oil facility in Oklahoma. (Courtesy of The Sherwin Miller Museum of Jewish Art)

In a business marked by booms and busts, at least some Jewish drillers have sought divine intervention, summoning aid through Jewish ritual. One of the early rabbis of Congregation B’nai Emunah in Tulsa, Harry Epstein, recounts an example in a book about the synagogue’s history:

One of the functions that developed upon the Rabbi was to recruit a minyan periodically to stay up all night, when one or another of our members was drilling a well for oil, and recite Tehillim [psalms] for the success of the drilling. Much to my sorrow I must confess that in many times we so gathered no well of oil came in and I consider this impotency of our prayers to be one of the failures of my administration.

An image of Jews striking black gold in oil country has even made it into popular culture. In the third season of “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” the mother of the show’s eponymous star character goes on a visit back home where viewers learn about the roots of her patrician demeanor. She belongs to an Oklahoma family of kippah-wearing oil drillers whose mansion is surrounded by oil derricks.

The charitable foundation associated with Oklahoma’s most famous and Jewishly engaged oil family, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, declined interview requests.

The Schustermans have become prominent because of the family’s leadership at virtually every important Jewish juncture of the past 35 years, with hundreds of millions of dollars donated to countless initiatives.

The family’s charitable endowment ballooned after 2011 when the Schustermans sold their company Samson Resources to a group of investors for $7.2 billion in one of the largest oil and gas transactions ever. (The timing turned out to be fortunate because within a few years, the price of fossil fuels dropped and Samson Resources filed for bankruptcy.)

Stacy Schusterman, meanwhile, had charted her own path, building up another company, called Samson Energy, which was focused on offshore drilling but is now involved in hydraulic fracturing projects in Wyoming’s oil and gas fields.

In the Jewish world, but also outside of it, the Schustermans’ foundation is known as a funder of liberal and progressive efforts in a wide array of areas, including voting rights, education, criminal justice reform and gender and reproductive equity. The family donates millions to Democratic party campaigns. A review of the foundation’s tax returns from 2017 to 2020 shows some $740 million distributed to more than 700 organizations, including JTA’s parent organization 70 Faces Media.

One progressive cause missing from their portfolio: the environment.

The Schusterman family responded to a request for an interview about its attitude on climate change given its involvement in the oil industry with a written statement:

“The Schusterman family is proud that their family business has enabled them to invest significant resources toward their philanthropic priorities, which include advancing racial, gender and economic equity in the U.S. and strengthening both the Jewish community and Israel. They believe abundant, affordable energy is vital to the economic well-being of the world’s growing population. They also support President Biden’s agenda to combat climate change and the goals he has put forward as part of the infrastructure and budget reconciliation bills. Finally, they have made investments in addressing climate change, including support for clean tech and efforts to protect the environment.”

Rabbi Jennie Rosenn, Founder and CEO of Dayenu, speaks as activists and demonstrators take part in a march and demonstration at the U.S. Capitol during the MoveOn and Poor People’s Build Back Better Action in Washington, D.C., Nov. 15, 2021 (Jemal Countess/Getty Images for MoveOn)

Grantmaking offers only a limited way to discern a donor family’s stance on climate, according to Cintra Pollack, who is active in Jewish philanthropy through the Singer Family Foundation. Named after her grandfather, the foundation represents the wealth of several generations of oil entrepreneurs in Oklahoma and Colorado.

While grants to environmental causes don’t appear in the foundation’s tax returns, the underlying endowment, or corpus, is heavily invested in clean energy, Pollack said.

“It’s not a focus of our grant making, but that doesn’t mean that climate change is something we don’t care about,” she said. “With our corpus, we’ve invested quite a bit so far in things like solar energy financing.”

Pollack’s approach to running the foundation comes from the world of impact investing, which is based on the idea that it’s possible to make financial decisions to benefit the public while also turning a profit. In that way, she sees her outlook not as a break from her family’s legacy but as a continuation of it.

“Even though, clearly, climate change and fossil fuels have been detrimental in so many ways, a lot of good has come out of using it — many people have been lifted out of poverty by industrialization,” she said. “Now we know better and do things differently as times change and that is very Jewish.”

Naomi Oreskes, a historian at Harvard University who is Jewish, authored the book “Merchants of Doubt,” parsing decades of propaganda on climate science funded by the biggest players in the oil industry. She showed how this propaganda effort helped stall policy initiatives to curb greenhouse gas emissions at a time when doing so would have been easier and made much more of a difference.

As far as she’s aware, the comparatively small oil companies that are owned by Jewish families have not played a role in the campaign to confuse the public about the threat of climate change. But Oreskes believes that not participating doesn’t automatically clear them ethically.

“There are sins of commission, and sins of omission,” she said. “One of the things that troubles me so much about our current situation is how many people who could have made a difference have stood on the sidelines and said nothing.”

Ella Rockart contributed research to this story.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.