(JTA) — It was the landmark 1993 handshake between Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and Israel prime minister Yitzchak Rabin that inspired Eli Evans to invest, for the third time, in “Sesame Street.”

As an executive at the Carnegie Corporation in the 1960s, he had brokered the government support that helped launch the fixture of American educational television. Then, after becoming the first president of the Charles H. Revson Foundation in 1977, he supported the creation of an Israeli version, “Rechov Sumsum.”

With peace in the air, Evans believed that an Israeli-Palestinian version was needed. He set out to convince other funders, Israeli and Palestinian government officials and noted artists to join the effort. Ultimately, dozens of episodes were made even as real-life prospects for peaceful coexistence were demolished — a testament to Evans’ unflinching optimism, forged during a childhood in the American South, in the power of partnership and creativity to create a more just society.

Evans died on Tuesday, two days shy of his 86th birthday, of complications from COVID-19 in New York City.

“Through his great generosity of spirit, love of Israel and the Jewish people, profound belief in the promise of American democracy, and philosophy of betting on audacious ideas and talented people, Eli contributed mightily to making our world a better place,” the Revson Foundation, which was founded by the Jewish founder of Revlon Cosmetics, said in a statement. “He was a role model and mentor to those who followed in his footsteps.”

Eli Nachamson Evans was born July 28, 1936, in Durham, North Carolina, to Emanuel “Mutt” Evans, a general store owner who in 1950 would become Durham’s first Jewish mayor, and Sara Evans, the founder of Hadassah’s first chapter in the South. His grandfathers had been immigrants and peddlers.

In “The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South,” the first of several books Evans would write on the topic, he detailed growing up a Jew in Durham, then a sleepy city drenched in the fragrance and money of the tobacco trade. He said the family experienced antisemitic comments and even threats but that his father was generally respected by both the city’s business elite and its Black population, in part because of Mutt’s savviness in navigating cultural norms. Campaign literature boasted about Mutt’s presidency of Beth El Synagogue to appeal to churchgoing voters, Evans wrote. Meanwhile, he noted that the family store was the first in Durham to have a racially integrated lunch counter — but that Mutt removed the seats as a concession to a segregationist backlash.

Evans’ decision to study literature at the University of North Carolina — where he was the first Jewish student body president and spent a summer on a kibbutz in Israel — and then go on to Yale Law School after a stint in the U.S. Navy spelled the end of the family business. It also meant that he would spend much of his adult life living outside the South, even as he returned whenever possible and maintained connections to the region through his philanthropy and writing.

After working briefly in politics, as a speechwriter to President Lyndon Johnson and an aide to North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford, Evans joined the Carnegie Corporation. There and later at Revson, he advanced a philosophy of activist grant-making focused on allowing talented people to carry out their own visions. His projects helped Marian Wright Edelman launch the Children’s Defense Fund, seeded the South with Black lawyers who became local civil rights leaders and built ties between Israeli and Egyptian scientists after their countries made peace in 1979.

“Private philanthropy has the freedom, privilege, and responsibility to do what government cannot,” Evans wrote in 1998, on the 20th anniversary of the Revson Foundation’s launch. “It can use its independence to take the long view, to forewarn, to support the unpopular, the visionary, the dreamers and their dreams. It can test new ideas, try new approaches, and bring together people of widely differing perspectives, disciplines, and talents to discover new avenues of mutual understanding.”

Though he lived in New York City for much of his adult life, Evans maintained deep ties to the South. When his wife gave birth to their son at New York University Medical Center, Evans brought a vial of dirt from North Carolina into the delivery room.

Eli Evans and his son Josh at Josh Evans’ wedding in 2015. (Courtesy Josh Evans)

“With one hand I held Judith’s hand, and with the other clutched the southern soil,” Evans wrote in “Home,” an essay about growing up Jewish in the American South that was one of many places where he recounted the delivery-room story. “I wanted him to know his roots.”

Evans wrote multiple books about Southern Jews in addition to “The Provincials,” including a biography of the Jewish Confederate leader Judah P. Benjamin and a second collection of personal essays in 1994.

Jonathan Sarna, the Brandeis University historian of American Jewry, said Evans stood out for his humility and receptiveness to new ideas. Sarna recalled a discussion in which Evans considered whether his family’s success in getting along with both white Christian and Black communities in Durham had been a product not only of their own tolerance but of racial dynamics in which white Jews served as a bulwark against a potential Black majority.

“Eli was a Southern gentleman who interacted with the Jewish establishment and strengthened American Jewish life, without losing his Southern Jewish soul,” Sarna said. “It was a privilege to have known him.”

“The Jews of the South have found their poet laureate,” Abba Eban, the 20th-century Israeli scholar and diplomat, wrote in praise of Evans’ second essay collection, “The Lonely Days Were Sundays.” Evans had been instrumental in backing “Civilization and the Jews,” a PBS series about Jews hosted by Eban that was one of the first Jewish initiatives of the Revson Foundation in the 1980s.

In a 1999 oral history about his work in philanthropy, Evans said the Revson board’s interest in the series was a turning point in his thinking.

“I thought, gee, this could be exciting to try to do, to build a foundation that would have both Jewish concerns, which were very natural to me,” and other concerns, he recalled.

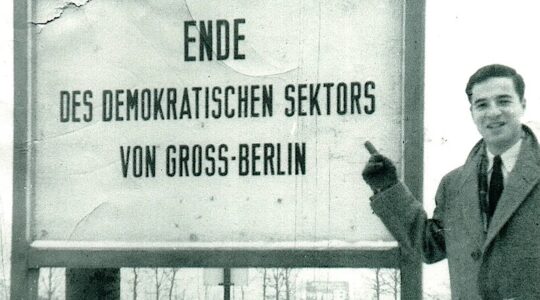

Eli Evans, seen here in a picture from a trip to Israel in the 1970s, was “equally at home in Manhattan, Jerusalem, and the American South,” according to his family. (Courtesy Josh Evans)

He advanced those concerns in 22 years as board chair of the Covenant Foundation, which funds Jewish education initiatives. Evans and his family were active members of New York City’s Brotherhood Synagogue for many years, and he traveled frequently to Israel. He also played an instrumental role in establishing the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies at UNC, to which Revson made a major gift in his honor after he retired from the foundation. Evans received an honorary degree from his alma mater in 2009.

“A warm, often ebullient storyteller who played banjo and wore his Carolina-blue Tarheels cap with attire both business and casual, he was equally at home in Manhattan, Jerusalem and the American South,” read an obituary of Evans prepared by his family.

Evans’ wife, Judith, died in 2008. He is survived by his son, the actor Joshua Evans, who said in the family obituary that he had come “to realize that my father’s superpower was his warmth and charm.” Evans will be buried in his family plot in Durham on Friday.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.