SITKA, Alaska (JTA) — It is a peculiar mystery that has endured for more than 120 years in the shadows of Mt. Verstovia on Baranof Island in southeast Alaska.

At 611 Lincoln St. in the heart of downtown Sitka, above the entrance to a Gothic Revival red-brick Episcopal church called St. Peter’s by the Sea, sits an intricately designed stained-glass window with eight flower petals in varying shades of blue and gold.

At the center of the window is something you typically don’t see in a place of prominence at a Protestant church: a star of David.

How the symbol got there is the subject of local folklore and an oft-repeated story recited by tour guides who shepherd cruise-ship passengers and other tourists around Sitka, a city of about 8,500 year-round residents that is close to 100 miles south of Juneau.

As the sign out front greeting visitors to St. Peter’s by the Sea notes: “Legends have grown up surrounding the origin of the beautiful stained-glass window at the front of the church, largely because it contains a star of David; however, the definitive story has yet to be told.”

Light shines through the stained-glass window from the inside of St. Peter’s by the Sea Episcopal Church. (Dan Fellner)

Wanting to learn the “definitive story,” I met with the church’s archivist, Gail Johansen Peterson, and Judge David Avraham Voluck, the unofficial leader of Sitka’s small Jewish community. Voluck, an attorney and tribal judge for the local Tlingit and Haida indigenous people, has lived in Sitka for a quarter-century.

“I’ll give you the urban myth,” Voluck said when asked about the window at a local hangout called the Backdoor Cafe. “But,” he added with a hearty laugh, “I’m talking out of my tuchus.”

Voluck, 52, who bears a resemblance to Topol in the movie “Fiddler on the Roof” and has a personality to match, told the same story I had heard the day before from a local guide during a bus tour of Sitka’s most prominent sites. When St. Peter’s was built in the late 19th century (it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978), its leaders ordered a stained-glass window from a manufacturer somewhere in the eastern United States. The intent was to have a Rose of Sharon adorn the center of the window.

“I guess it took about a year of waiting,” said Voluck. “First, it’s got to be made, then it’s got to be packed. And then it’s got to be shipped. But some shlemiel in the shipping department must have got the windows crossed.”

On a cold November day in 1899 — much to the dismay of the local Episcopalians — the wrong window arrived. With winter soon arriving and a cold draft blowing through the gap, church leaders had to make a quick decision about what to do.

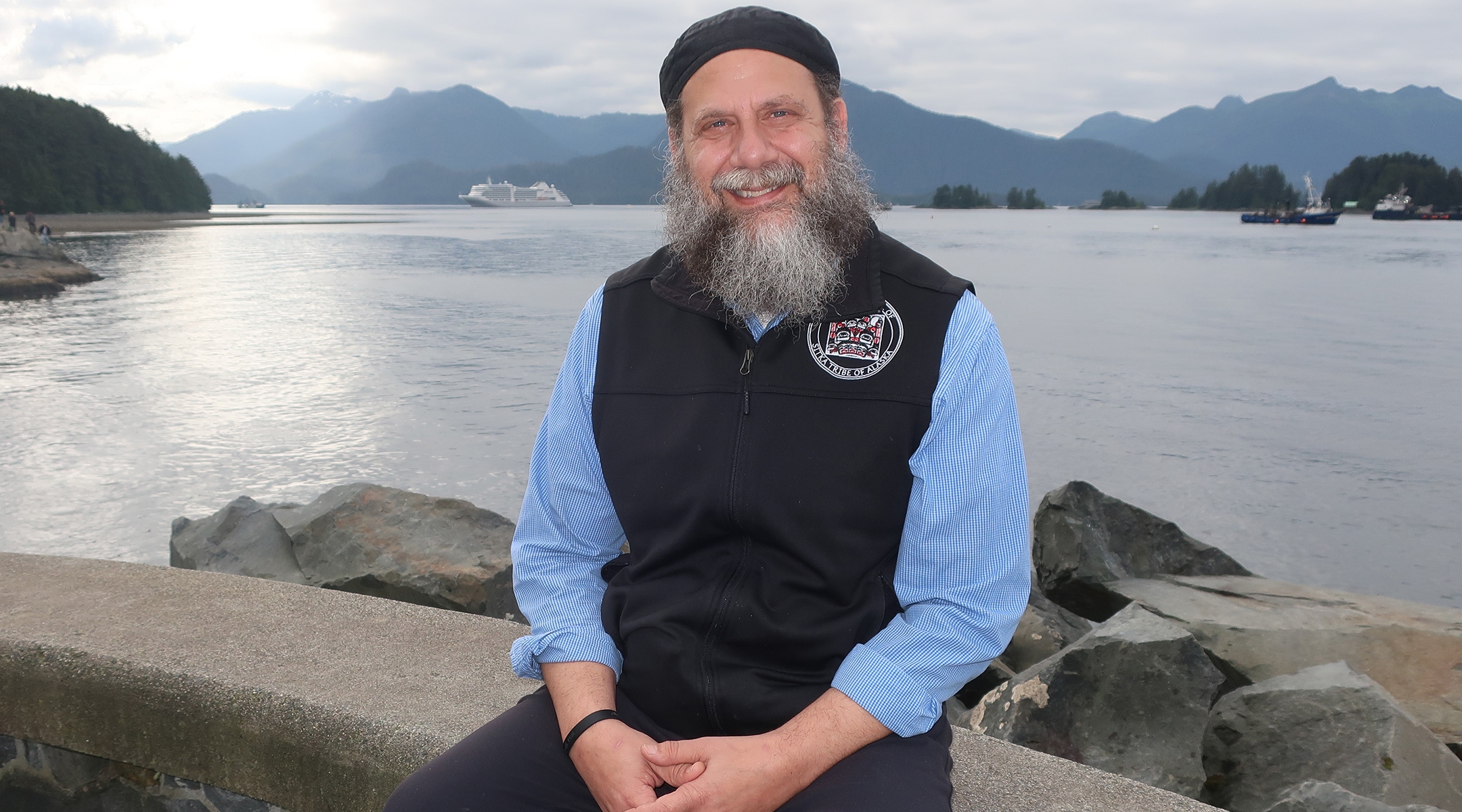

Judge David Avraham Voluck, the unofficial leader of Sitka’s small Jewish community, is an attorney and judge for the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. (Dan Fellner)

“It wasn’t exactly what had been ordered but the people who made the decisions at that time found that it was acceptable to keep that window because it harkened to the Old Testament,” said Johansen Peterson, adding that — over the decades — it proved to be the right decision.

“Everyone in the congregation is really quite enamored with it because it lends itself to our Judeo-Christian traditions,” said Johansen Peterson, who has belonged to St. Peter’s for more than 40 years.

Kathryn Snelling, the church’s current deacon, agreed, saying the window has “remained a beloved part of St. Peter’s by the Sea over the years.”

“I have never heard a disparaging comment about it. Visitors do ask, and we share the story and the mystery,” she added.

Was there a miscommunication in the process of designing the window? Did a synagogue somewhere else receive the window that was intended for the church in Sitka? Johansen Peterson said the definitive answer will likely never be known.

Voluck, who was born and raised in Philadelphia, graduated from the Lewis & Clark Law School in Oregon with a Certificate in Environmental Law. After law school, he joined an Alaskan law firm, specializing in federal Indian law. He traveled to rural villages throughout the state, providing representation to Tlingit, Haida and other Indigenous peoples. In 2008 he was appointed Chief Judge of the Sitka Tribal Court. Voluck is considered one of Alaska’s pre-eminent experts on Indian Law and Tribal Courts.

As a Jew, Voluck says he’s developed a strong kinship with the indigenous people with whom he works.

“I refer to them as my ‘cousins’ and it’s sympatico,” he says. “We have a tribal background. We’re survivors of genocide. And we cling tenaciously to our history.”

Mt. Verstovia overlooks the harbor in Sitka, Alaska, a community of about 8,500 year-round residents. (Dan Fellner)

Twenty years ago, seeking to strengthen his connection with Judaism, Voluck took a two-year hiatus from his work in Alaska to attend the Rabbinical College of America in New Jersey, where he focused on Talmudic and Jewish Legal Studies.

He guesses that about 50 Jews live in Sitka, not enough to sustain a synagogue or any kind of regular events. “I used to have dreams of that,” he said. “Maybe I’m running out of gas. Each year my tank gets a little lower.”

Voluck calls himself the Jewish community’s “lay leader,” which fits well with Sitka’s informality. It’s a place where “Orthodox” is far more likely to refer to someone who worships at the local Russian Orthodox church — reflecting Sitka’s history as a Russian settlement — than an observant Jew.

“There is no hierarchy in Sitka; we all come to Judaism and offer whatever we have,” said Voluck, who has kosher meat flown in once a month from Brooklyn. “It seems to work. But if someone has a Jewish question or issue, they usually seek me out one way or the other.”

For now, Voluck is content serving Alaska’s indigenous people, raising his three children in a kosher home, hosting Israeli tourists for Shabbat dinners and occasionally cobbling together a minyan for a yahrzeit service.

As for the window at St. Peter’s, Voluck calls it a wonderful conversation starter.

“I think it’s great that there’s a star of David on display in the center of our town,” he said. “I don’t know how it ended up here, but I love it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.