(JTA) — As a kid I went to Sunday school at our Reform synagogue. I didn’t hate it as much as my peers did, but let’s just say there were literally dozens of other things I would have preferred to do on a weekend morning.

As a Jewish adult, I had a vague understanding that Sunday school was a post-World War II invention, part of the assimilation and suburbanization of American Jews (my synagogue was actually called Suburban Temple). With our parents committed to public schools and having moved away from the dense urban enclaves where they were raised, our Jewish education was relegated to Sunday mornings and perhaps a weekday afternoon. The Protestant and Catholic kids went to their own religious supplementary schools, and we Jewish kids went to ours.

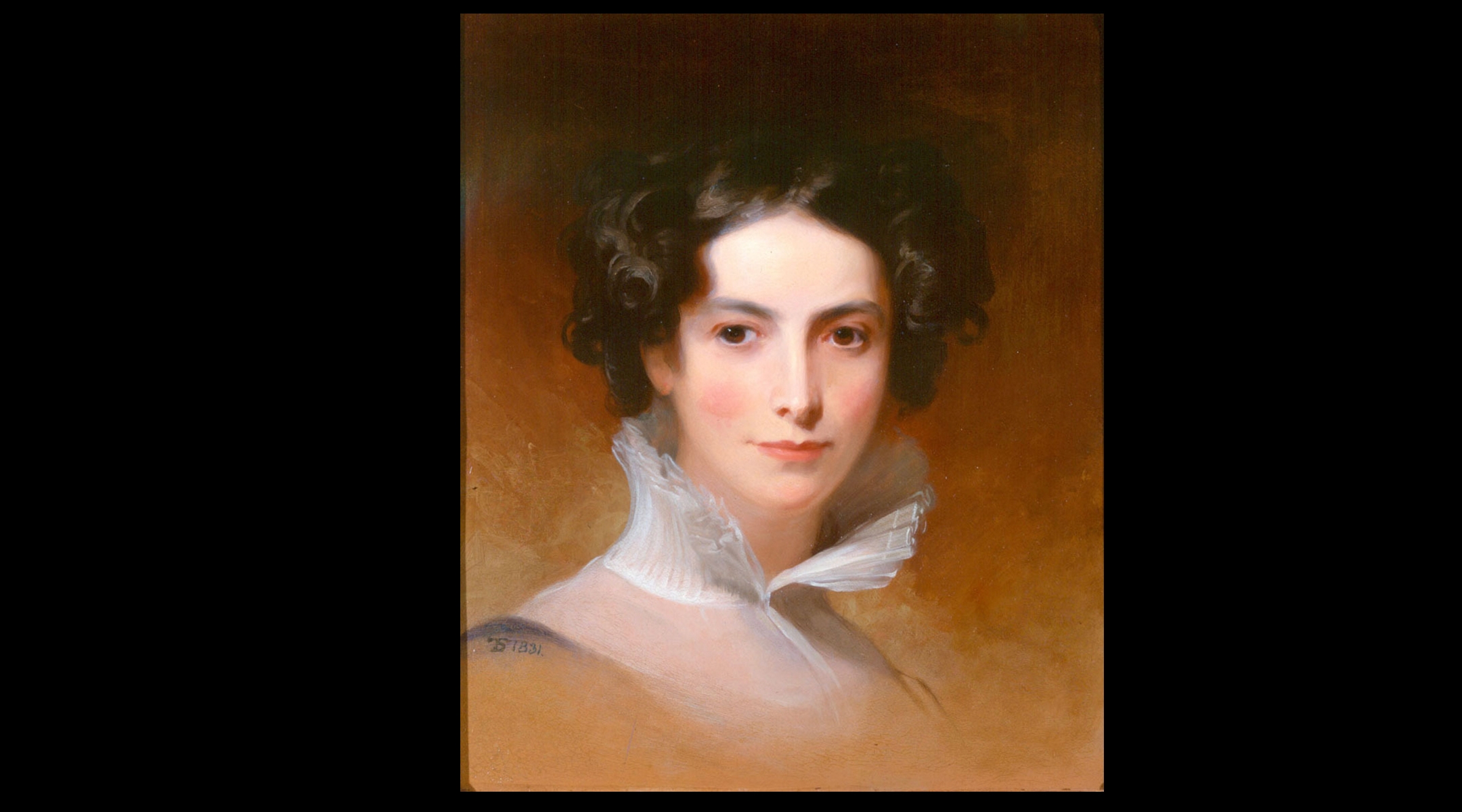

In her new book “Jewish Sunday Schools,” Laura Yares backdates this story by over a century. Subtitled “Teaching Religion in Nineteenth-Century America,” the book describes how Sunday schools were the invention of pioneering educators such as Rebecca Gratz, who founded the first Sunday school for Jewish children in Philadelphia in 1838. As such, they were responses by a tiny minority to distinctly 19th-century challenges — namely, how to raise their children to be Jews in a country dominated by a Protestant majority, and how to express their Judaism in a way compatible with America’s idea of religious freedom.

Although Sunday schools would become the “principal educational organization” of the Reform movement, Yares shows that the model was adopted by traditionalists as well. And she also argues that 20th-century historians, in focusing on the failures of Sunday schools to promote Jewish “continuity,” discounted the contributions of the mostly volunteer corps of women educators who made them run. Meanwhile, the supplementary school remains the dominant model for Jewish education among non-Orthodox American Jews, despite recent research showing its precipitous decline.

I picked up “Jewish Sunday Schools” hoping to find out who gets the blame for ruining my Sunday mornings. I came away with a new appreciation for the women whose “important and influential work,” Yares writes, “extended far beyond the classrooms in which they worked.”

Yares is assistant professor of Religious Studies at Michigan State University, with a joint appointment in the MSU Program for Jewish Studies. Raised in Birmingham, England, she has degrees from Oxford University and a doctorate from Georgetown University.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Tell me how your book came to be about the 19th century as opposed to the common 20th-century story of suburbanization.

There’s a real gap in American Jewish history when it comes to the 19th century, chiefly because so many American Jews today trace their origins back to the generation who arrived between 1881 and 1924, the mass migration of Jews from from Eastern Europe. So there’s a sense that that’s when American Jewish history began. Of course, that’s not true at all.

The American Jewish community dates back to the 17th century and there was much innovation that laid the foundations for what would become institutionalized in the 20th century.

Sunday school gets a very bad rap among most historians of American Judaism. If they’ve treated it at all, they tend to be dismissive — you know, there was no substance, they just taught kids the 10 Commandments, it was run by these unprofessional volunteer female teachers, so it was feminized and feminine.

But there’s also a lot of celebration of Rebecca Gratz, who founded the first Sunday school for Jewish children.

That’s the first indication I had that there might be more of a story here. Rebecca Gratz is lionized as being such a visionary and being so inventive in developing this incredible volunteer model for Jewish education for an immigrant generation that was mostly from Western Europe. And yet, by the beginning of the 20th century, [Jewish historians] say it has no value. So what’s the story there?

Two other things led me on the path to thinking that there was more of a story in this 19th-century moment. I did my Ph.D in Washington, D.C. And as I was searching through the holdings of the Library of Congress, there were tons and tons of Jewish catechisms.

“Sunday school gets a very bad rap among most historians of American Judaism,” says Dr. Laura Yares, author of the new book, “Jewish Sunday Schools.” (Courtesy of the author)

A catechism is a kind of creed, right? It’s a statement of religious beliefs. “These are things we believe as Jews.”

So Jewish catechisms had that, but they were also philosophical meditations in many ways. Typically, the first question of the catechism was, what is religion? And then the second question is, what is Jewish religion?

And then I started reading them. They were question-and-answer summaries of the whole of Judaism: belief, practices, holidays, Bible, you name it, that the children were expected to memorize. This idea that you’ve got to cram these kids with knowledge went against this historiographic dismissal of this period as being very thin and that kids were not really learning anything. The idea that children had a lot to learn is something that Sunday school educators actually really wrestle with during this period.

What was the other thing that led you to pursue this subject?

When I was beginning to research my dissertation, I was working as a Hebrew school teacher in a large Reform Hebrew school in Washington, D.C. And I remember very distinctively the rabbi coming in and addressing the teachers at the start of the school year. He said, “I don’t care if a student comes through this Hebrew school and they don’t remember anything that they learned. But I care that at the end of the year they feel like the temple is a place that they want to be, that they feel like they have relationships there and they have an (he didn’t use this word) ‘affective’ [emotional] connection.”

And so I’m sitting there by day at the Library of Congress, reading these catechisms that are saying, “Cram their heads with knowledge.” What is the relationship between Jewish education as a place where one is supposed to acquire knowledge and a place where one is supposed to feel something and to develop affective relationships? The swing between those two poles was happening as far back as the 19th century.

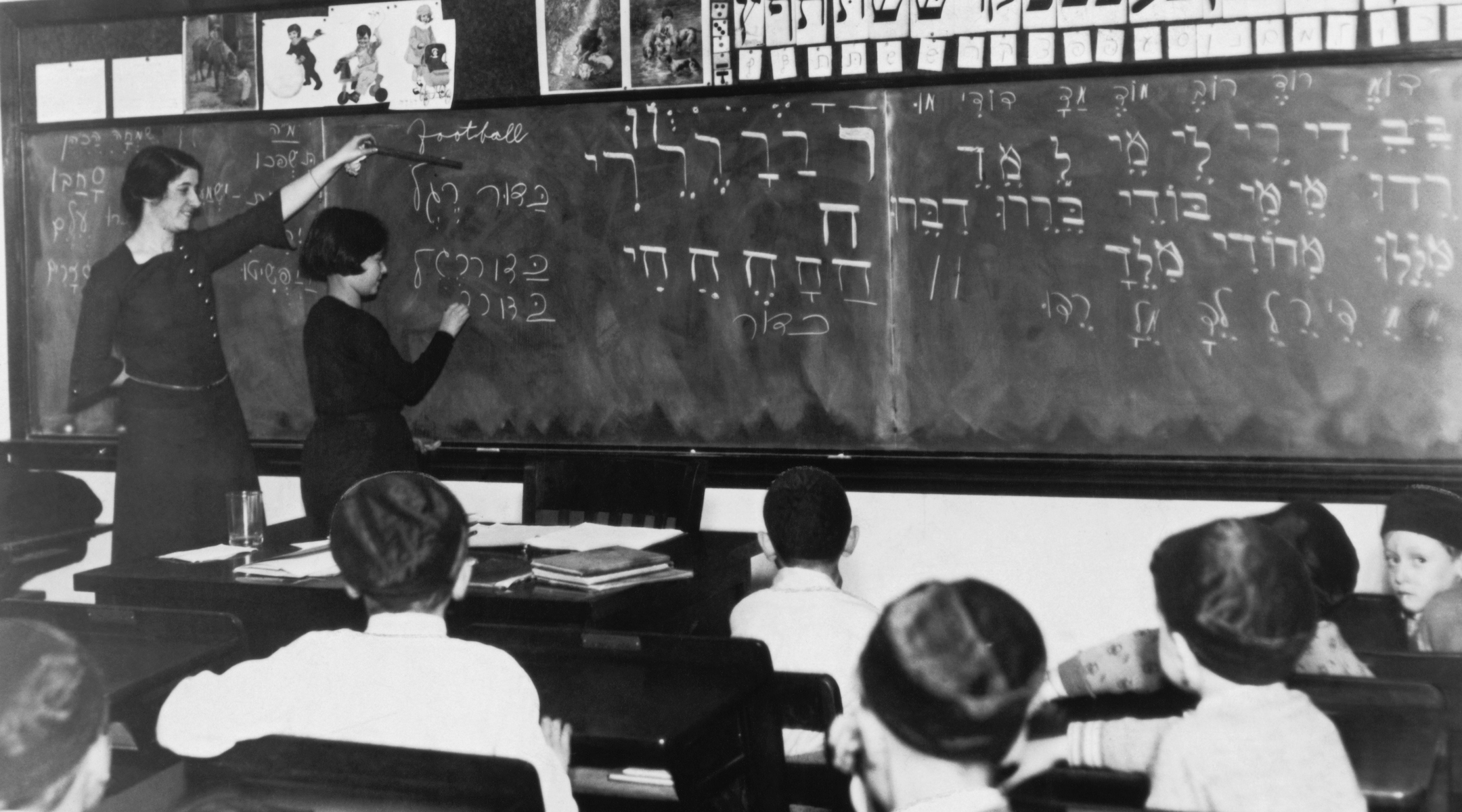

You write that owing to gaps in the archives, it was really hard to get an idea of the classroom experience. But to the degree that there’s a typical classroom experience in the 1860s, 1870s and you’re the daughter or grandchild of probably German-speaking Jewish immigrants, maybe working or lower middle class, what would Sunday school be like? I’m guessing the teacher would be a woman. Are you reading the Bible in English or Hebrew?

You are probably going for an hour or two on a Sunday morning. It’s a big room, and your particular class would have a corner of the room. It’s quite chaotic. Most of the teachers were female volunteers. They were either young and unmarried, or older women whose children had grown. Except for the students who are preparing for confirmation — the grand kind of graduation ritual for Sunday schools. Those classes were typically taught by the rabbi, if there was a rabbi associated with the school.

There would be a lot of reading out loud to the students with students being expected to repeat back what they had heard or write it down so they had a copy for themselves. Often the day would begin with prayers said in English, and often the reading of the Torah portion, typically in English, although in many Sunday schools, we do have children reporting they learned bits of Hebrew by rote memorization. Or they memorized the first chapters of the book of Genesis, for example, but I’m not sure that they quite understood what they memorized. “Ein Keloheinu” is a song that often children tell us [in archival materials] that they had memorized in Hebrew. They probably would have learned at least Hebrew script, and a little bit of Hebrew decoding. But it is fair to say that if they were reading the Bible, they were reading it mostly in English, because you have to remember that most of the women who were volunteering to teach in these schools came of age in a generation where Hebrew education wasn’t extended to women.

What’s the goal of these Sunday schools?

The Sunday school movement arose because there was a whole generation of immigrant children who did not have access to Jewish education, because their parents didn’t have either the economic capital or the social capital to become part of the established Jewish community. They couldn’t afford a seat in the synagogue, they couldn’t afford to send their children to congregational all-day or every-afternoon schools [which were among the few options for Jewish education when Gratz opened the Philadelphia Sunday school]. Sunday schools are really a very innovative solution to a problem of a lack of resources.

You also write that the founders of these supplementary schools want to defend children against “predatory evangelists.”

That was how Rebecca Gratz described her goal when she created the first Sunday school. She was very, very worried about the Jewish kids who were not receiving any kind of Hebrew school education. She talks about Protestant missionaries and teachers who would go out onto the street ringing the bell for Sunday school and offering various kinds of trinkets, and Jewish kids would get kind of swept into their Sunday schools. There was a very concrete need to give Jewish children somewhere else to go.

So Gratz and the people who created the first Hebrew Sunday school in Philadelphia looked at what the Protestants were doing and they saw that Protestant Sunday schools were providing very accessible places where kids could go and get a basic primer in their religious tradition.

The approach was to teach Judaism as a religion, as opposed to Judaism as a people or culture, to demonstrate that being Jewish was as compatible as Protestantism with being wholly American.

That is certainly part of it. It’s a demonstration that Judaism is compatible with American public life. But I think there’s actually a much bigger claim that the Sunday schools are making. The claim is not only that Judaism is as good as Protestantism, but that Judaism does religion better than Protestantism. These rabbis who were writing catechisms and teaching confirmation classes were saying that Judaism does liberal religion better than liberal Protestants, liberal Catholics and other kinds of liberal denominations. You see the same sentiment in the Pittsburgh Platform as well, which is the foundational platform of the Reform movement written in the 1880s. Sunday schools take that idea and bring it down to a grassroots level.

There are many, many fewer Jews in America in much of the 19th century, before the waves of Eastern European immigrants arrived beginning in the 1880s They didn’t really have strength in numbers, or the kind of self-confidence to have a system of day schools, yeshivas or heders, the elementary schools for all-day or every day Jewish instruction.

And this is also a community that has grown up at the same time as the birth of public education in America, independent of churches. That really emerged beginning on the East Coast in the 1840s.This generation of Americans really believes in the power of public education to craft an American public. It’s a project that 19th-century American Jews believe in and want to sustain. So Sunday schools don’t just become the preferred Jewish model because of lack of resources, but because American Jews really believe in the idea of public education.

What happens at the beginning of the 20th century, with the arrival of Eastern Europeans with different models for Jewish education?

A new generation tries to reform Jewish education, led by a young educator from Palestine named Samson Benderly, who leads the new New York Bureau of Jewish Education. He tries to change American Jewish education to make it more professionalized, but to bring more traditionally inclined Jews on board he has to convince them that he doesn’t want to make more Sunday schools, because Sunday schools by the end of the 20th century had become very much associated with the Reform movement in a way that they weren’t when they were founded and for much of the 19th century.

A painting of Philadelphia philanthropist and Jewish education activist Rebecca Gratz by Thomas Sully. (The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia)

Benderly is surveying the scene of recent immigrants living in New York City [tenements] and other kinds of downtown environments, and his proposal is to create these community institutions for these dense communities, where children can be taught Hebrew in Hebrew. His disciples also created Jewish camps as a way to get children out of the inner cities and develop the muscular Zionist ideal of healthy bodies and a robust sense of Jewish collectivity.

You write that Benderly’s vision is a sort of masculine response to the “feminizing” perception of the Sunday schools.

These women teachers are recognizing that they’re being criticized for the kind of thinness of the Jewish education that they’re teaching in comparison to other models, but in periodicals like The American Jewess women are writing back and saying, “But you didn’t teach us Hebrew! I didn’t get that opportunity as a woman, so what do you expect?” It’s really important to note that the women did the best that they could in the time that they had available, and that they were the product of opportunities that were denied to them.

What lessons did you learn about Sunday school and Hebrew school education in the 20th century that relate to your research into the 19th century?

The move that is so decisive for shaping American Jewish education is suburbanization. Rather than having a large immigrant generation who are living in these tight ethnic enclaves, you have American Jewish children who are predominantly growing up in the suburbs, and socializing with children from all sorts of different backgrounds who are attending public schools. The place that you go to get your Jewish education is the synagogue supplemental school, which becomes the dominant model for American Jewish education up until today. Benderly might reflect that it looks a lot more like the Sunday school movement of the 19th century than his vision.

Today’s model is really a religious model. And by that I mean that students go to Hebrew school primarily to kind of check a religious box, to learn about the thing that makes them distinctive religiously, and to achieve a religious coming-of-age marker, which is the bar, bat or b mitzvah. Certainly the curriculum today is more diverse, embracing more aspects of traditional Judaism then you would have seen in a 19th-century Sunday school: more Hebrew, more of a sense of Jewish peoplehood, ethnic identity and Zionism of course. But the question that American Jews are increasingly asking themselves is, is this a model that they still want? So you may have seen that the Jewish Education Project published a report recently on supplemental schools, which saw that enrollment has really, really declined.

Sunday schools are based on a vision of Judaism as a set of a religious commitments that American Jews actualize through belonging to a synagogue and sending their children to a synagogue or a religious school, where they will learn primarily a set of religious skills: the ability to read from the Torah, the ability to decode Hebrew, the ability to navigate the siddur.

Is that still the vision that most American Jews have for what Judaism means to them? I think increasingly the answer seems to be no.

How else did experience in a Hebrew school classroom influence you? Did you access anything else when you were writing the book?

I think about the number of college kids and graduate students and empty nesters who are either volunteering or earning minimum wage, working at Hebrew schools, all over the country. That’s the labor force of American Judaism. These people also bring so much to the table. There are a lot of skills, dispositions and knowledge that don’t tend to get taken very seriously because this is a workforce that just gets kind of put into the category of “oh, they’re part time.” That made me look really closely in the historical archives to see if I could find anything out about the women who are volunteering to teach in Sunday schools. And what I found out was that [many] were public school teachers. And they brought a lot to the table. It was women in fact who were really pushing to make the Sunday school curriculum more experiential and to move away from rote memorization.

As a historian formed by feminist methods, I find it really important to recognize that these women were giving over what they had, as opposed to critiquing them for not teaching in a more traditional way. I think we need to pay attention when women are being scapegoated for problems that are described as problems of Jewish continuity. It blinds us to the role that women’s volunteerism has played in American Jewish life. This whole Sunday school movement was possible only because these women volunteered their time and largely were not paid.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.