Ethel Berman, 82, walks with a cane and her vision is so poor she needs help placing her hand on the spot where she is supposed to sign a check.

But Berman is proud to be living at the Warbasse apartments in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, where she not only takes care of herself but volunteers to organize programs to benefit other residents of the heavily senior-citizen complex at the corner of Ocean Parkway and Neptune Avenue.

"This is the closest thing to being independent," said Berman, who has been living at Warbasse since it was built in the early 1960s.

That measure of independence comes with the help of state funds, administered in the lobby of her building through an agency called Warbasse Cares for Seniors.

A project of the Jewish Association of Services for the Aged, Warbasse Cares serves as a second family for several hundred seniors at the cooperative. It does everything from checking their blood pressure to driving them to the kosher butcher.

But with the state facing a budget deficit as high as $10 billion, Berman and other members of an increasingly graying Jewish community are caught in the crossfire between Republican Gov. George Pataki and Democratic Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver.

Pataki wants to eliminate $1.2 million in aid to naturally occurring retirement communities, or NORCs, as part of his proposal to reduce state spending. Silver considers the NORC funding one of his legislative godchildren and has vowed to protect it.

Thousands of seniors across the city are launching a campaign to oppose the cut. Many will converge on the Educational Alliance in Manhattan on March 27 for a protest rally.

"We need to inform our legislators that this is unacceptable," said Anita Altman, deputy managing director for resource development at UJA-Federation, who is working to organize the opposition to the cuts.

A UJA-Federation report on New York Cityís Jewish population due this spring is widely expected to show dramatic increases in both the number of elderly Jews and the portion of those elderly that require assistance.

"We’ve succeeded in helping people extend their longevity," said Altman. "Now we have to help them maintain their quality of life."

By funding health screening, program referral, transportation and other services for seniors at Warbasse and 29 other sites, all but two in New York City, legislators believe the state saves itself, the city and federal government millions in Medicare tabs at nursing homes or hospitals.

"Trying to save $1.2 million is penny wise and dollar foolish because it will drive senior citizens into much more expensive institutional care and wind up costing the state $20 million," said Silver, whose own Lower East Side cooperative has been designated as a NORC.

The speaker believes Pataki, who tried unsuccessfully to eliminate the NORC funding shortly after he was elected in 1995, is out to undo many of Silver’s signature programs.

"This is part of his overall strategy to take out every initiative from the Democratic leadership, and me specifically," said Silver, noting that Pataki also wants to restore sales tax on clothing valued under $100, eliminate Universal Pre-K child-care programs and reduce aid for neighborhood development zones.

Kevin Quinn, a spokesman for Pataki on budget issues, said the 9-11 terrorist attack and national recession required "some very tough choices, including reductions in programs in which [Pataki] personally believes. The best way to support this program [in the future] is to adopt a budget that creates new jobs and a growth economy."

Quinn said seniors in NORCs would be able to access assistance through another program, Community Services for the Elderly, which remains fully funded.

But Altman of UJA-Federation said that program has a two-year waiting list, is open only to applicants who meet certain criteria and does not include services administered by groups like Warbasse Cares.

Although Warbasse Cares receives funding from UJA-Federation and other private nonprofits, the state is its largest single benefactor, contributing $143,000 this year, more than a quarter of its total budget. That’s roughly the equivalent of the salaries of three full-time social workers, without whom the agency’s programs would have to be sharply curtailed.

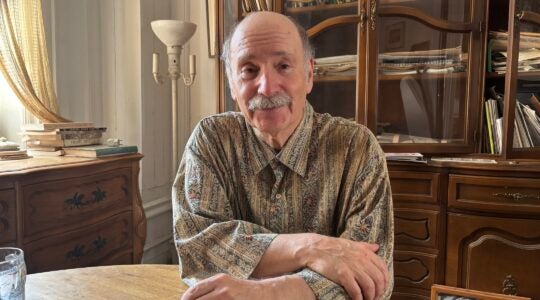

Walter Lasky, who like Berman has been living at Warbasse since it was built ("before they had sidewalks," he said) plans to take part in a write-in campaign as well as the rally at the Educational Alliance in Manhattan.

"Pataki should be made aware of the importance of this program," said Lasky, 77, a retired credit manager. "A place like this is paradise for seniors."

Although he has a car and is less dependent than many neighbors on Warbasse Cares, he participates in the book club and museum outings as a means of socializing.

"I’m just beginning to get into senior life," said Lasky, chatting Friday at the Warbasse Cares headquarters, which is about the size of a dentist’s office. "This is a fantastic operation."

He says he and other tenants have organized a system of "floor captains" to check on each other’s welfare, as most have either no children or children who live far away.

Losing the state funding would amount to a double blow to Warbasse Cares. The Metropolitan Jewish Health System has been providing nurses on the premises on a regular basis, but because of its own cutbacks will end the practice as of July 1. That’s a major setback to seniors who have grown accustomed to finding medical assistance no further away than the lobby of their own building.

"Many of them call us before they call 911," says Karen Stieber, director of Warbasse Cares. "We know there are literally hundreds of seniors who don’t go to the ER each year because of the services here."

Some 95 percent of the clients at Warbasse Cares are Jewish, many of whom keep kosher but can no longer shop in the immediate neighborhood.

"The demographics have really changed," said Stieber. "The merchants have left, but the seniors still have the same needs."

The agency maintains two vehicles to transport shoppers to neighborhoods where they can find kosher butchers or bakeries.

Stieber notes that the six-figure grant from the state enables them to "leverage" other private grants, which are usually one-shot infusions.

"Philanthropy usually does not stick around," said Stieber.

The organization was founded in 1993, and it wasn’t until 1995 that it obtained state funding.

Berman said she never feels ashamed to stop by the office to ask someone to read her a letter, and programs like music and dance classes get her out of her apartment.

"I’m totally dependent on this office," she said. "You don’t like to bother your neighbors. You won’t have friends too long if you keep calling on them."

Added Lasky: "What do I do when I can’t drive anymore? This program becomes even more important to me."

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.