The proprietors of the small kiosks in The Diamond Exchange on West 47th Street, the heart of Manhattan’s Diamond District, decorate their working areas with artifacts to give each an individual touch. There are family photos, religious icons and homeland decals.

John Kaufmann, a native of Germany, has attached a pair of small stuffed koalas to the spine of his desk lamp. They’re a reminder of Australia, where as one of the Dunera Boys he spent eight years.

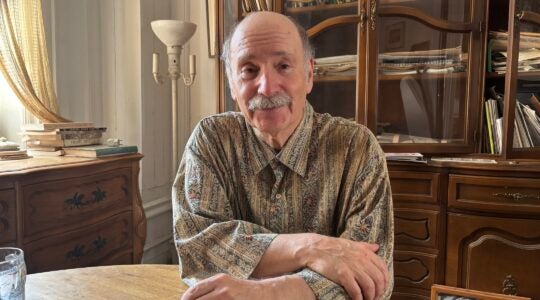

Kaufmann, 80, a diamond setter here for a half-century, is among several hundred one-time British internees in Australia who settled in the United States after England realized its error and gradually released the 1,997 Jewish men starting in early 1942.

A widower who has lived in New Rochelle for four decades, Kaufmann has told his two sons about his wartime experiences. But few Americans, even Jews, have ever heard about the Dunera, he says. If customers show an interest in his story, he pulls from his kiosk drawer a booklet of drawings (he’s a self-taught artist) and descriptions (in German, of course) he created while in England, onboard the Dunera and in Australia.

"I got lucky," Kaufmann says of his escape from the Nazis’ Final Solution. "I’ve been lucky all my life."

After immigrating alone to England, being arrested there and interned and shipped to Australia, joining the Australian army for a few years and working in Melbourne as a diamond setter, he survived World War II. So did his parents, who moved to the United States after some time in a French concentration camp. All four of his grandparents died in the Holocaust.

He talks matter-of-factly about his early years. He received his British visa at 16, at the end of August 1939, a week before the war began. "I just made it out," he says.

Kaufmann found work in the diamond trade in Birmingham. "That’s where they arrested me," he says. He had heard the rumors that "they were arresting refugees." One suitcase in hand, he went to a transport camp near Liverpool. One day a major announced, "All those wishing to go overseas step forward." More rumors ó the Jewish refugees would be taken to Canada. Kaufmann says he volunteered, figuring Canada might mean freedom.

One of the Jews on the Dunera read the stars one night. "We are not going to Canada," he told his shipmates. Finally, at the end of a 22,000-mile journey during which the prisoners were confined to their rooms for 232 hours a day, they found out that Australia was their destination.

The Jews were taken by train to the Hay camp, 19 hours from Sydney. They stayed in unheated barracks and tents. "We didn’t need heat," Kaufmann says. "It was 110 in the shade."

There was no forced labor and no recreation for the prisoners. No radio or newspapers; no word about the war or about families back home. The day began at 7 a.m., lights out at 10 p.m. "It was pretty boring," Kaufmann says.

He carved little chess figures. The Jewish community of Sydney sent some books to read. "We played games, sports. I played bridge. I played a lot of chess," Kaufmann says.

Release came in the spring of 1942, "when they decided we weren’t Nazis after all."

Like many of the Jews, Kaufmann joined the Australian army. He was a private, unarmed, remaining in Australia until the war ended. A rabbi with roots in Germany helped arrange Kaufmann’s job. Kaufmann says he "was working and having girlfriends." Then he decided to reunite with his parents, who had settled in Queens.

In later years, as an American citizen, he and his wife visited Australia "four or five times," attending some of the annual Dunera reunions. He also went back, with his wife, whom he had met in the United States, to Germany.

Kaufmann subscribes to the Dunera newsletter, but he hasn’t kept in touch with his fellow Dunera Boys. He rarely thinks about Australia’s outback, circa 1940.

"It was quite an experience," he says. "No one should go through it: but we did."

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.