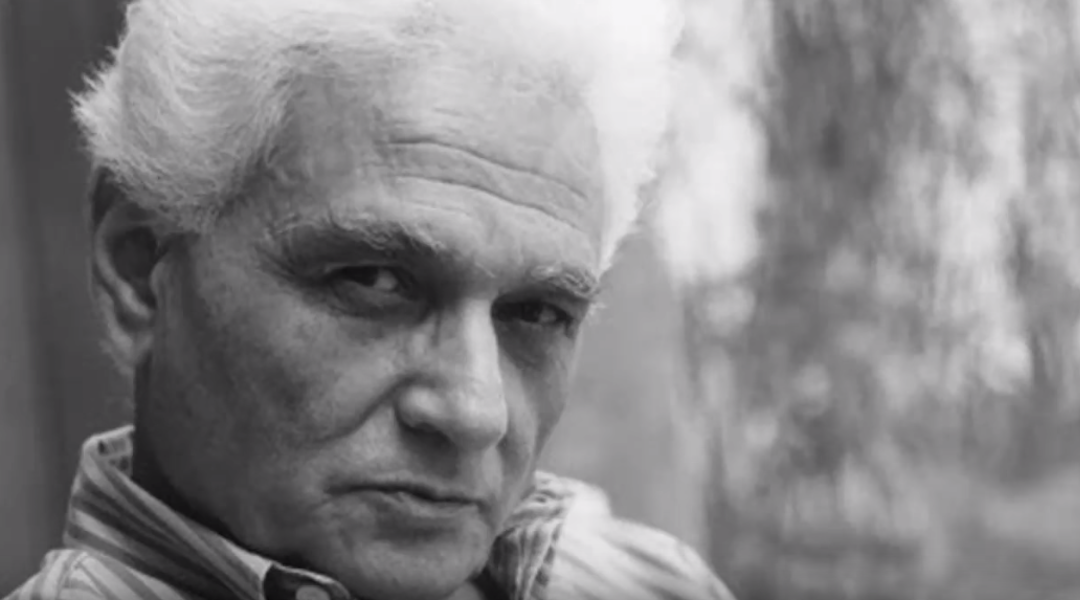

Jacques Derrida, the founder of “deconstructionism” who died recently in Paris, will be remembered as one of the most important philosophers and Jewish thinkers of the past century. Derrida’s impact reached not only the fields of philosophy and literary theory, it also opened the door for new blood and fresh ideas in Jewish Studies.

Derrida’s academic followers in the United States were responsible for popularizing the study of midrash and the use of midrashic ideas to comment on all varieties of literature. His work opened the door for rabbinic texts and methods to become popular in the secular academy, beyond Jewish Studies departments.

Though Derrida never impacted popular Jewish culture in the United States, he had a profound influence on an important group of Jewish Studies scholars, including Edith Wyschograd, Elliot Wolfson and Daniel Boyarin, along with others who applied his questions to Jewish texts and Jewish problems.

Derrida’s personal history was interwoven with the complex history of the French Jewish community. Raised in a Sephardic Jewish family in Algeria during the French colonial period, he was expelled from school when the Vichy government barred Jews from the classroom.

Derrida’s family relocated to France in 1949, and he taught at the Sorbonne and the Ecole des Hautes Etude en Sciences Sociales in Paris, but he was displaced from what he felt to be his home.

As a leading French intellectual who was both inside and outside the Jewish community, inside and outside Europe, inside and outside the philosophical academy, Derrida’s life embodied some of the contradictions and paradoxes of being Jewish in modern Europe.

Derrida was ambivalent about how significant his Jewishness was to his work. Helene Cixous, the French feminist philosopher who also grew up in an Algerian Jewish family, explored this ambivalence in a book titled “Portrait of Jacques Derrida as a Young Jewish Saint.”

Derrida was closely associated with leading Jewish thinkers and writers in France, working in dialogue with Emmanuel Levinas, the revolutionary moral philosopher who wrote volumes of essays on the Talmud, and passionately advocating Edmond Jabes, whose novels about the Holocaust were filled with the maxims of fictitious rebbes.

Derrida even signed one of his essays “Reb Derrisa” — meaning, perhaps, “the rabbi who laughs” — reminding his readers both of his Jewish background and of his connection to Jabes’ characters.

Derrida’s philosophy was part of the postwar zeitgeist that rejected modernism and structuralism — or, more simply, that rejected the idea of real progress and the existence of real identities.

Derrida famously said, “There is no thing outside the text,” and his writings were full of the kind of language play and neologisms that allow one to reinterpret words without end.

Though Derrida’s work was extraordinarily difficult to read, the practice of deconstruction, which uses tools of interpretation to read “against the grain” of a text, can be explained as a method for showing that any text is “undecidable” and that every act of writing will create meanings diametrically opposed to the author’s intention.

One of the important philosophical terms that Derrida coined was “logocentrism,” referring to Plato’s belief that the spoken word is worth more than the written word. This idea, which influenced all of Western philosophy, claimed that the “presence” of the speaker in the “logos” or “word” was filled with special meaning, while the written word was devalued by the author’s “absence.”

In Christian thought, the same idea was used to devalue Judaism; the presence of the “Logos” was opposed to the rabbis’ passion for the letter of the written word. In essay after essay, Derrida showed that this hierarchy of speaking over writing was self-contradictory and even unjust.

Derrida’s writings often took the form of commentaries, and he spoke about writing “in the margins of philosophy,” as one of his book titles proclaimed. By validating the reader over the writer and the unintended over the intended meaning, Derrida unleashed a powerful movement to read texts subversively, independent of their explicit message.

Responding to his work, some promoters of Derrida in America, like Geoffrey Hartman of Yale University and Susan Handelman, formerly of the University of Maryland and now at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, claimed that deconstruction represented the emergence of a new kind of “secular midrash,” a kind of Jewish or rabbinic method within Western and Greek-influenced thought.

The idea that everything was textual and that all possible contradictory meanings could be contained within any text is remarkably parallel to the way the rabbis approached Torah, and this parallel was intoxicating for many Jewish scholars.

However, for Derrida, God, like the author of any text, was an absence, not a presence that could back up a text’s meaning.

Jewish literary scholars like Harold Bloom, who linked criticism with Kabbalah, embraced deconstruction, while Jewish Studies scholars often resented the encroachment of Derrida’s surrogates into their domain.

Derrida never fully explored Jewish texts in the way someone like Levinas did in his “talmudic readings,” but he did write about Biblical and Jewish motifs on numerous occasions.

In some academic seminars, Derrida focused exclusively on Jewish texts and themes: In one, he explored a letter from Gershom Scholem to Franz Rosenzweig about the “apocalyptic abyss” that was created by the resurrection of spoken Hebrew in Israel, and in another, he discussed Spinoza’s cryptic statement that the practice of circumcision would allow the Jewish people to resurrect their kingdom.

Both texts were rife with the kinds of complexities Derrida loved to pick apart and analyze, but they also gave him reason to explore the contradictions of nationalism and the poignant struggles that confront the Jewish people today.

In the latter part of his career, Derrida deepened his exploration of Biblical themes, writing books on the binding of Isaac — “The Gift of Death” — and on Abraham’s hospitality and the nature of justice — “Of Hospitality,” quoted above.

Derrida’s colleagues brought him to Yale in the 1970s, and he continued to teach in the States, most recently at the University of California at Irvine. Last year, Derrida participated in a number of forums on deconstruction and religion at different campuses that involved the subjects of faith, prayer, justice and God.

Elliot Wolfson of New York University wrote that, for Derrida, “the Jew embodies the impossible, which he came to understand as prayer, or better, the prayer for the possibility of praying, in his own words ‘the prayer before the prayer, the prayer for the prayer.’ ”

Derrida’s work embraced what some saw as moral nihilism and others saw as intellectual liberation. Derrida himself became the object of intense controversy after the wartime fascist sympathies of one of his close collaborators, Paul DeMan, were revealed in the same year that Derrida published a book about his philosophical father Martin Heidegger that discussed the meaning of Heidegger’s Nazism.

DeMan, who taught at Yale for many decades, had written for a pro-fascist paper in occupied Belgium. When Derrida defended DeMan’s integrity while only thinly critiquing his wartime writing, critics from both conservative political circles and from Jewish Studies departments saw this as proof that deconstructionism was incapable of taking a moral stand.

Yet Derrida always maintained that deconstruction was inherently political and was focused on taking responsibility. Even while denying the possibility of knowing truth, Derrida was a sharp advocate for human rights and freedoms.

As early as 1969, in his first public talk in the United States he spoke about the Vietnam War, and he continued to take public stands throughout his career on issues like apartheid, immigrant rights and the death penalty.

Later in his life, Derrida questioned Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, while at the same time upbraiding Palestinian supporters for “anti-Jewish tendencies.”

Derrida’s work will continue to affect Jewish Studies and Jewish philosophy, even when the name of “deconstruction” is transformed from the hot academic fashion it once was to an object of historical study. May his remembrance be a source of blessing.

David Seidenberg, who studied with Derrida in the summer of 1986, has a doctorate in ecology and Kabbalah and is a Conservative and Renewal rabbi who teaches in California and throughout North America.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.