The millennial generation’s growing detachment from Israel, creeping doubts about theological fundamentals, declining numbers in the pews and a more significant backing for female clergy than one might expect — these are just a few of the findings gleaned from a first-of-its-kind study on the Modern Orthodox community, a diverse and vocal group that represents approximately 4 percent of the American Jewish population.

The survey, titled “Nishma Research Profile of American Modern Orthodox Jews,” is being reported on for the first time here. The survey’s results—spanning hot-button issues from the day school tuition crisis to acceptance of LGBTQ Jews to the roles and status of women—quantified what some have conjectured to be a growing divide between liberal strains of Orthodoxy and the denomination’s more conservative ones.

Results point towards a “net rightward shift” of 16 percent.

An analysis of observance found that 39 percent of respondents reported becoming more observant over the last decade, while 23 percent of respondents reported becoming less so, pointing towards a “net rightward shift” of 16 percent. (These numbers reflect the overall self-perception of respondents; a separate section of the survey measured observance by keeping Shabbat, kashrut, putting on phylacteries every day — among males — and observing the laws of family purity among married couples).

Those who reported decreasing levels of observance came exclusively from Orthodoxy’s more liberal camps, the self-identified “liberal” and “open” Orthodox. Those in more conservative camps — self-identified as “right centrist,” “centrist” and “modern” Orthodox — all reported increasing levels of observance. Liberal segments of the community also reported a much higher percentage of their children becoming less observant.

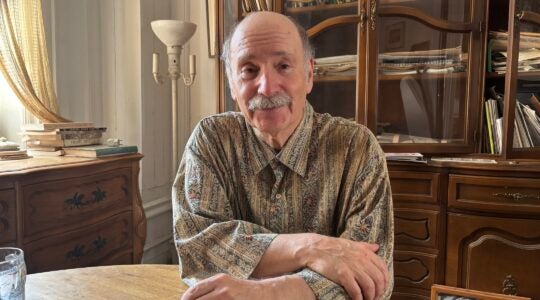

“The fabric of Modern Orthodoxy is being stretched,” said Mark Trencher, lead researcher and author of the report. Trencher, a former public policy analyst and market researcher, said that the data indicates a “growing schism” in the Orthodox community.

“The community is becoming fragmented,” he added.

“Polarization increases the diversity within Orthodoxy. The study shows “greater diversity than the image of the Orthodox appears.”

Nishma Research is a sociological and market research firm that studies targeted segments of the Jewish community. (Most recently, the research group conducted an in-depth survey of those who have left the Orthodox fold, a community colloquially referred to as “Off the Derech,” or path.) The new survey, which used a web-based, opt-in survey rather than a random sample, analyzed the responses of 3,903 American Modern Orthodox adults 18 and older.

Steven M. Cohen, research professor of Jewish Social policy at HUC-JIR and a member of the study’s advisory panel, said the survey’s “polarization hypothesis” — that the left is moving further left and the right further right — mirrors a broader sociological trend within other American religious groups.

“Polarization increases the diversity within Orthodoxy,” said Cohen. The study shows “greater diversity than the image of the Orthodox appears.”

Rather than harming Modern Orthodoxy, the drop-off in observance among the more liberal Orthodox might be viewed as encouraging, said Sylvia Barack Fishman, professor of contemporary Jewish Life at Brandeis University.

“The presence of children who are less observant is very positive,” she said, noting that for most of the 20th century, those who did not fit into Orthodoxy would simply defect. Rates of retention are “infinitely better” than they used to be, thanks in great part to liberal strains of Orthodoxy giving younger people “a religious home,” she said.

“Orthodoxy is nurturing a broader spectrum of young people because we’re seeing the movement stretch to include people who have more liberal views.”

The “stretch” was particularly evident when it came to shifting attitudes towards sexuality and acceptance of LGBTQ Jews. One third of respondents said their attitudes towards sexuality have changed, most citing an increased acceptance of gay Jews; 58 percent of respondents support synagogues accepting gay members, and 72 percent report being “OK with it.” While support is highest among the liberal factions, significant support exists on the right as well (24 percent of the right-most cohort support gay Jews joining their synagogues).

The survey revealed fault lines about the role and status of women. The study found widespread support for women serving as synagogue presidents — 74 percent of respondents approved of women serving in this role, an indication of significant movement within the community, said Trencher. There was also nearly unanimous support for women learning Torah on an equal intellectual level to men — with less than .5 percent opposing — strong support for co-ed classes (80 percent), women-friendly mechitzas (75 percent), women reciting Kaddish without men (69 percent) and women giving sermons from the bima (65 percent).

When it came to women serving as clergy, 53 percent of respondents believe that women should have the opportunity for such expanded roles; 38 percent said they strongly or somewhat support women in clergy holding a title of rabbinic authority. The largest dissent — at 94 percent — came from the right centrist cohort.

“I fear the spectre of a schism,” said Steven Bayme, director of Contemporary Jewish Life at the American Jewish Committee and a member of the study’s advisory group. “There is a fundamental split in the community about how visible and present women should be in roles of authority and leadership within the synagogue.”

This divide is playing itself out right now, as the Orthodox Union, the largest Orthodox umbrella organization, decides what to do about its four member synagogues that have women serving in clergy roles. Earlier this year, the OU published a major report written by seven prominent rabbis concluding that women in rabbinic roles should be prohibited. A letter signed by an estimated 50 Modern Orthodox rabbis asked the OU not to “expel” these synagogues.

“I would hope the OU takes these results seriously.” – Steven Bayme

“I would hope the OU takes these results seriously,” said Bayme, referring to the study’s finding that a majority of respondents support women in clergy roles. “This is not just a matter of four outlying synagogues — virtually half of the Modern Orthodox population wants some sort of recognition of women in clergy roles. That’s a critical split.”

Still, others were not convinced that Trencher’s findings indicated a significant schism within Modern Orthodoxy.

“I fear the spectre of a schism.” – Steven Bayme

“Religious groups can persist with great diversity before undergoing a schism,” said sociologist Cohen. Signs of a “true schism” would be members of different segments refusing to marry one another, or hire each other’s religious leaders, he said. “I don’t see that happening.”

The divide, said Cohen, is more about cultural liberalism and conventional Orthodoxy.

“Can Orthodoxy adjust to find a space that would be as attractive to liberals as it is to conservatives?” said Cohen. “Cultural liberals tend to like diversity, while the Orthodox community conventionally prides itself on a certain level of uniformity.”

This schism is also political, and marks a break between Orthodoxy and the broader Jewish community, said Bayme. Only 43 percent of respondents support a two-state Mideast solution, a position espoused by many mainstream Jewish organizations. There is also a marked division of views between Orthodox and non-Orthodox on President Donald Trump’s performance; a recent AJC survey found that 71 percent of Orthodox respondents viewed Trump’s performance to date favorably, compared to the vast majority in all other denominations viewing Trump’s performance unfavorably. (AJC’s survey did not distinguish between ultra-Orthodox and Modern Orthodox.)

One of the study’s most concerning findings, experts say, is a decrease in emotional connection and active support of Israel. While 87 percent of those 55 and older report feeling emotionally connected to Israel, 65 percent of those ages 18 to 34 feel the same way. And while 71 percent of those 55 and older actively support the Jewish state, less than half — 43 percent — of Jews 18 to 34 do the same.

While 41 percent of men age 55 and older reported attending shul on a weekday morning, only 18 percent of men ages 18 to 34 reported doing so.

“Decreasing political activism on behalf of Israel among the young Modern Orthodox flies in the face of our assumptions,” said Bayme. The data is particularly unnerving given the common practice among the Modern Orthodox to send high school graduates to Israel for a gap year before beginning college. While decreased attachment to Israel was widely recognized for young people in other denominations — Birthright Israel began trips in 1999 to address the problem — this was “always thought not to be true among the Orthodox,” said Bayme.

Another trend mirrored by Modern Orthodox youth: a decreased interest in the importance of synagogue and the belief that prayer is meaningful. While 50 percent of those 55 and older found prayer to be meaningful, 32 percent of those under age 45 found prayer to be meaningful. And while 41 percent of men age 55 and older reported attending shul on a weekday morning, only 18 percent of men ages 18 to 34 reported doing so. (Two percent of all women reported doing so.)

“Asking millennials to come to shul is often asking them to deny the essence of who they are,” said Rabbi Elie Weinstock, rabbi of Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun on the Upper East Side and a member of the survey’s advisory panel. The hierarchical nature, questions about gender equality, and the culture of obligation makes conventional synagogue practice foreign to a generation that values individual identity and expression. “It’s a challenge and an opportunity,” he said, referring to how to best engage young people. Innovation, he said, is key. “Sometimes sacred cows have to be slaughtered.”

Issues central to Orthodox faith are also in a further state of ferment than one might assume. While 64 percent of respondents believe the Torah was given at Sinai — a tenet of Orthodox faith — 36 percent of respondents only “tend” to believe this or have doubts. While 51 percent of respondents believe God is involved in their lives, 49 percent only tend to believe this or have serious doubts. The theological “ferment,” as referred to by Bayme, is heavily weighted in the liberal Orthodox camps.

“We don’t want to rock the boat so much that people fall overboard.”

Rabbi Weinstock, responding to these findings, said that “we have to recognize that Modern Orthodoxy is challenged by modernity,” adding: “Judaism demands a lot more than belief in God. Throw in confronting the modern world and staying committed to Judaism — it’s a tremendously difficult balance.”

Innovation within tradition has to be balanced with concerns of the older demographic, said Rabbi Weinstock.

“We don’t want to rock the boat so much that people fall overboard.”

In a ranking of “top problems” faced by the Jewish community, respondents ranked the “cost of Jewish schooling” far and away the most serious challenge facing the Modern Orthodox world. Ninety seven percent of respondents consider it a problem. (The second problem with the highest ranking concern was agunot, women trapped in lapsed marriages because their husbands refuse to provide a religious divorce.)

The exorbitant price of day school education is driving 17 percent of respondents to consider other schooling options, a number some experts found “surprising.”

“Modern Orthodoxy has always been praised for making Jewish education non-negotiable,” said Bayme. For one-sixth of the community, that is no longer the case, due in large part to expense, he said. “The ironclad commitment to Jewish education among the Orthodox relies on a system that can accommodate its members.”

Still, despite significant challenges and dissent over core issues, the survey shows that Modern Orthodoxy is alive and well, and will remain vital for the Jewish future.

“Two generations ago, the Modern Orthodox were thought to be a dying element within the community,” noted Bayme. With a birthrate that more than replaces their ranks (though the number dwarfs in comparison to the birthrate of the ultra-Orthodox), having a future is not the question. “Today, the issue is not whether Modern Orthodoxy is here to stay. The issue is what type of Orthodoxy are we talking about.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.