AMSTERDAM (JTA) — Opposite the Dutch national bank here lies one of Europe’s least conspicuous monuments to a war hero.

Titled “Fallen Tree,” the metal statue for resistance fighter Walraven van Hall looks so realistic that for months after its unveiling in 2010, the municipality would receive calls reporting the artwork, whose brown-painted branches are strewn over a small square, as storm debris in need of removal.

A departure from the bombastic reliefs commemorating other European World War II heroes, it’s a fitting tribute to van Hall. For decades he had gone unrecognized even in his own country, despite the fact that he used cunning and courage to save hundreds of Jews from the Holocaust while inflicting painful damage on the Nazi war machine before his execution by German soldiers in 1945.

This year, however, van Hall’s bravery for the first time has moved from obscurity to the mainstream thanks to the production of a multimillion-dollar feature film titled “The Resistance Banker,” which won the Netherlands’ national award for best film in 2018 and is the country’s submission to the Oscars.

The film, where the persecution of Jews plays a central role, is the first treatment of its kind about the actions of van Hall and his brother, Gijsbert — members of a prominent banking family who for three years bankrolled the Dutch resistance, supplying it with the equivalent of $500 million.

It’s a surprisingly long delay considering the scale of van Hall’s actions, which historians say helped make the Dutch resistance one of Europe’s fiercest and most effective. There are also powerful dramatic elements in the van Hall story, a tale full of valor, betrayal, death, devotion — and even a bank robbery of unprecedented proportions.

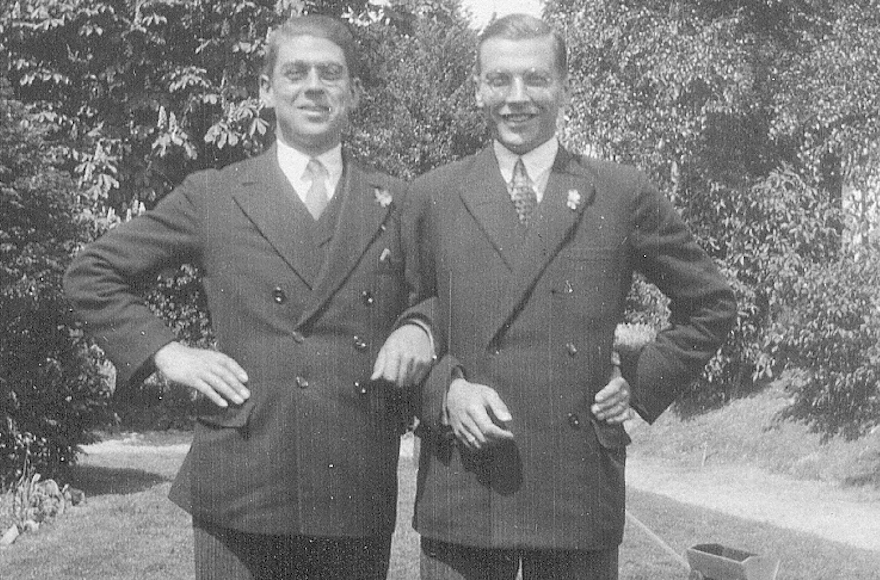

Walraven van Hall, right, and his brother Gijs in the 1930s. (Courtesy of the van Hall family)

Dutch moviegoers have noticed. With 400,000 ticket sales, it is by far the highest-grossing locally made film production in the Netherlands this year and one of the industry’s all-time hits, according to the De Volkskrant daily. It debuted in Dutch theaters in September and is now available to watch in the United States on Netflix.

“When people think of the resistance … they rarely think of the enormous amounts of money that it cost to keep this organization — the resistance — running,” the film’s director, Joram Lürsen, told JTA.

But resistance leaders knew this all too well when they were joined in 1942 by van Hall, an ex-marine with banking connections, whom Israel recognized in 1978 as a Righteous Among the Nations – a non-Jew who risked his life to save Jews during the Holocaust.

He and his brother stole the equivalent of $250 million from Nazi-controlled coffers and borrowed an additional $250 million from other bankers to carry out attacks, smuggle Allied pilots to safety and provide financial support to at least 8,000 Jews in hiding during World War II.

They did all this “through an incredibly complicated web of front companies, falsifications and bureaucratic sleight of hand that is tricky to pack into a two-hour feature film,” or even a biographical novel, Lürsen said. An attempt to “truly explain the genius of their actions” would lose most filmgoers within the first 20 minutes, he said.

To tackle this storytelling challenge, Lürsen focused on the most daring action undertaken by the brothers: The theft and cashing in of central bank bonds, which at that point wasthe largest-scale bank robbery in European history.

“This one element of the story contains everything you need in a Hollywood action film,” Lürsen said. “It’s as easy to follow and full of suspense as a casino heist.”

From left: Jacob Derwig, Barry Atsma and director Joram Lursen after winning the Golden Calf film award at the Netherlands Film Festival in Utrecht, Holland, Oct. 5, 2018. (Courtesy of the National Film Festival of the Netherlands)

Not everyone is pleased with the shortcuts and artistic license that Lürsen and his team have taken.

Harm Ede Botje, a senior analyst for the Vrij Nederland magazine and an expert in World War II history, accused the filmmakers of gratuitous melodrama and disregard for historical detail in a withering critique of the film in March.

He noted a powerful scene in which an exhausted van Hall, nicknamed Wallie, draws resolve from seeing from the window of his train a transport of Jews in cattle wagons zooming past as fellow passengers look away in embarrassment. But Ede Botje says that Jews were never transported in the daytime in occupied Holland.

In the film, the trigger for van Hall’s decision to enter the resistance is the suicide of a Jewish family of former clients in Zaandam. But there is no evidence to suggest this is true — and no records of such a suicide in that suburb of Amsterdam, according to Ede Botje.

“It’s true,” Lürsen said of how persecution of the Jews is highlighted and perhaps amplified in his film. “I made a film about two courageous brothers, their lives, their love. Of course I had to make cinematographic and dramaturgical decisions, but it was important to include in a digestible way the background. Should I have spent less attention to the worst genocide in Dutch history because I have no evidence of Wallie ever witnessing it? I don’t think so.”

Another departure from the historical record diminishes the van Halls’ incredible ability to evade Nazi detection, Botje writes. In the film, van Hall is executed two months before the war’s end after the Germans and collaborators identify him as van Tuyl and the “oil man” — one of the many false identities he wore.

But in reality, the Germans had no idea who van Hall was to the bitter end. He was shot along with several other suspected resistance fighters in retaliation for a Nazi officer’s assassination. Historians to this day do not know why the Germans arrested van Hall.

This Amsterdam monument commemorates Walraven van Hall. (Wikimedia Commons)

The relative obscurity of the van Halls’ story — despite its significance, it has been the subject of only one dryly written book, in the 1990s — owes to more than just its complexity.

“For many decades there was a reluctance in the banking industry of this country to go into the details of the van Halls’ actions, because doing so would expose many of the system’s weak points,” Lürsen said. “No one wanted to publish a manual for mass bank fraud.”

But the industry changed over time, and the unofficial veil of silence that bedeviled historians’ attempts to get to the bottom of the van Halls’ operation was lifted.

Gijsbert van Hall, the elder brother, who later became mayor of Amsterdam, kept a meticulous record of each and every cent dispensed by his operation. Auditors after the war found no discrepancies in the bookkeeping after studying it for months.

The Netherlands had many collaborators with the Nazis, who helped murder 75 percent of the country’s Jewish population — the highest death rate in Nazi-occupied Western Europe.

But for the size of its population and Jewish minority, it also had a vastly disproportionate number of Righteous Among the Nations — 5,669 of them, the second-highest number in the world, trailing Poland’s 6,863. Many of the rescuers’ efforts were facilitated by the support extended to them by the van Halls.

Holland also saw the first major show of public disobedience over the fate of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe in the so-called February Strike of 1942.

For a small, flat country with few natural hiding places like woods, marshes or mountains, resistance to the Nazis was in some respects “fierce,” and in no small part thanks to the actions of the van Halls, according to Johannes Houwink ten Cate, a historian who is one of the world’s leading experts on the Holocaust in Holland.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.