(New York Jewish Week) — Yiddish literature and culture flourished between the World Wars, in tandem with a dizzying variety of mostly leftist, mostly secular political movements, from socialism, to Zionism, to Bundism, to Communism. The various political streams had their own school systems that required reading materials. Born out of this ferment was a lively children’s literature, often overlooked and forgotten in the shadow of the Holocaust and the catastrophic loss of a vast Yiddish-speaking civilization.

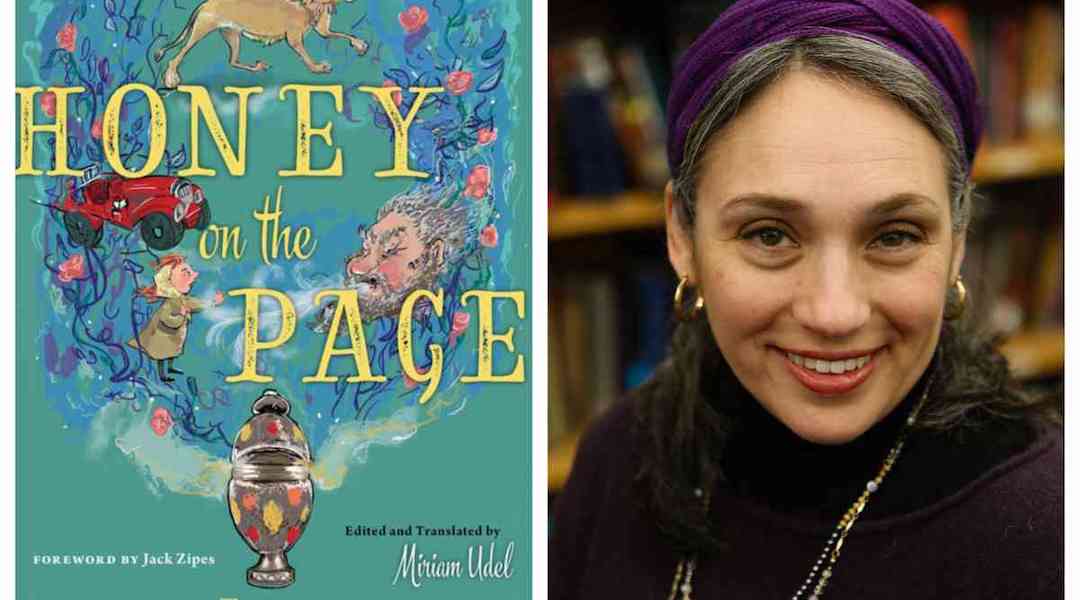

In “Honey on the Page: A Treasury of Yiddish Children’s Literature” (NYU Press), Miriam Udel collects and translates 50 of these stories and poems. They represent the range of styles and preoccupations of authors – some well-known, many obscure – who wrote in Yiddish for juvenile audiences, some into the 1970s. Although meant to be read by and to young people – and featuring whimsical illustrations by Paula Cohen – the book gathers a body of work that, writes Udel, is “essential…to understanding Jewish history and culture in the twentieth century.”

Udel, associate professor in German Studies and the Tam Institute of Jewish Studies at Emory University, spoke to The Jewish Week from her home in Atlanta.

New York Jewish Week: You tweeted that you worked on this for seven years. Tell me what that entailed.

Miriam Udel: My first book was a monograph on Yiddish modernism. I finished writing it in 2013, and it was published in 2016. I was casting about for a new project and at the time I had children who were 9 and 5 and I was teaching Yiddish classes, and the convergence of these two things – as a mother an language teacher – led me to ask, Is there any children’s literature in Yiddish? I started noodling around on the Internet and was blown away that there was a corpus of about 1,000 children’s books and periodicals. Not only had the books mostly been digitized by the Yiddish Book Center and made freely available on the Internet, but synopses were produced by volunteers. It was all just right there, ready for somebody to do something with. I ended up reading a lot of bad children’s literature, a lot of dross, but 10 percent was excellent.

Who were the authors?

The people are as diverse as literature itself. One category are educators, writing for pedagogical journals, for whom fiction writing is an offshoot of their educational leadership. And then there were high literary figures who wrote for children. In Yiddish and Hebrew, almost every significant literary figure who wrote for adults at least tried writing for children at some point.

I shouldn’t be surprised that a Jewish literature is so infused with political debate, but is an ideological thrust always apparent in Yiddish children’s literature?

Sometimes the ideology is subtle, and sometimes much more specific. There is a story, “The Birds Go On Strike” — by Simkhe Geltman, who wrote for children under the name Lit-Man — about country birds who become aware of the plight of the birds in the city trapped in cages. The free birds withhold their singing until their brethren are free. It turns out the sun can’t rise as a result and the whole natural order is disrupted. The world grinds to a halt until the children come out in the forest to negotiate. It was taking the familiar methodology of collective bargaining and importing it to a more whimsical situation.

The Labzik stories by Khaver Paver, about a dog adopted by an ardently Communist family, are explicitly political adventures, but they stand on their own because the family is so richly and beautifully drawn. In one story the bosses decide to extend the workday, and the whole family goes along to picket, and on the subway down to the sweatshop, the daughter explains to the dog how a strike works.

Did you have a chance to meet any of the authors or had they died before you were able to?

The authors are gone, but I was aware of surviving relatives, from whom I sought permission, and with whom I talked about the project. I talked with the grandson of Solomon Simon, the author of “A Deal’s a Deal” – his name is David Forman, and he teaches Yiddish at Cornell. But far and away, the most fun was connecting with the surviving son of Malka Szechet, the author of “What Izzy Knows About Lag B’Omer.” Her son is named Maximo, or Mordkhe, Szechet, and he lives in Omaha, and his mother was the only author for whom I could find no biographical record. A superhero librarian at the New York Public Library’s Dorot Jewish Division, Amanda Siegel, helped me piece together a very rudimentary life through ship’s manifests and plane manifests, and got me the names of the children and I found my way to Rav Maximo. We ended up speaking for an hour and a half in a conversation that unfolded in Yiddish, Spanish, English and Hebrew, as if my whole graduate education was so I could have this conversation.

Tell me more about the critic Samuel Charney, who was the longtime editor of the New York-based Kinder Zhurnal, a children’s magazine affiliated with the Shalom Aleichem schools.

Charney was his given name. He wrote under the pen name “Niger,” which has become problematic because “Charney” means “black.” He was far and away the most towering figure in Yiddish literary criticism for adults for decades. At the same time for 25 years he was editing Kinder Zhurnal. That speaks to the sense of urgency and importance these cultural activists had about creating a Yiddish literature for children.

As a kind of a postscript, his daughter Elizabeth Shub, who worked in publishing at Harper & Row and Greenwillow Books, told his friend Isaac Bashevis Singer that American parents spend a lot of money on books for their children. This was in 1965. He came back with a very stilted manuscript, and she told him to go back and try again. Then he wrote “Zlateh the Goat,” which became a classic, and he went on to publish 14 volumes of children’s literature.

You write that “Yiddish children’s literature developed in an atmosphere of urgency, as an effort not only to bring about an affirmative vision but also to forestall a catastrophe of neglect.” This is not just about the Holocaust exterminating a civilization, but about assimilation undermining the language.

By the time Yiddish becomes self-aware as a modern language and a vehicle for culture, it is already embattled on every imaginable front. Amerike ganef – America the thief — will steal Yiddish culture and send the children into linguistic assimilation. There’s the great struggle between Yiddish and Hebrew in the nascent state of Israel. In Russia, Yiddish finds its most congenial home in the USSR of the ’20s, but that shifts in the ’30s with a lot of assimilation into Russian. Everywhere you look people are starting to leave behind Yiddish.

So the promulgation of these stories is really a project of cultural preservation and an effort to forestall that catastrophe of neglect.

And after the Holocaust, it become a project of cultural consolidation and restoration. Even secularists were writing holiday tales, wanting children to be familiar with themes of Chanukah and Sukkot and Lag B’Omer.

Do any of the stories directly address the catastrophe of the Shoah?

In the novella “The Story of a Stick,” Zina Rabinowitz addresses it very explicitly. It’s a saga of four generations, the youngest of whom is a 13-year-old boy in Warsaw who is orphaned and living in a children’s village in pre-state Palestine. We see his experiences of the war.

The other way the Holocaust is addressed is by indirection. Another long piece is a life of Don Isaac Abravanel, the great leader of Iberian Jewry at the time of the Inquisition and expulsion from Spain. It was written by Isaac Metzker in 1941, and published during the Holocaust by the Kinder Ring, the children’s arm of the Workmen’s Circle, using events of 1492 to talk about the events of 1940-1941.

In many ways all these stories feel haunted by the Holocaust and its losses. How do you acknowledge that in a book meant, as you write, for families to enjoy together?

Two aspects – one is that in the biographical notes, I am very frank about relating the circumstances of the authors’ life and death, and a lot of the authors died violently at the hands of the Nazis and Stalin. Those notes are in a different typeface, which connotes that they are for the older reader.

Perhaps even more disturbing is the hauntedness of stories that were born into the world and then lose their readership. For the stories published in New York and Latin America, that is a case of acculturation, but for those published in Eastern Europe, there was a generation of readers that got truncated, and the second generation of readers wasn’t there. But I hope that heaviness won’t be felt by the youngest readers. Three or four generations post-Holocaust, I think we’ve moved away from the sense, once so keenly felt, that “you have to live for these children who didn’t make it.” That is a heavy burden to place on these kids.

I also see a hopefulness because Yiddish is going through a renaissance on multiple fronts. I hope this book will be part of that – putting a joyful, lively Yiddish on the radar for a lot of kids when they decide, as college students or young adults, that they are going to go study this language and reclaim this heritage that might have been attenuated in their family.

You address these young readers in your introduction. It sounds like you very much want these stories read by their target audience, as opposed to just being studied by scholars. Why do you think it important for children or teens today to be reading these stories from another time?

I tried to select stories that would stand on their own and be compelling for contemporary kids. Some of them feel old-fashioned, which makes sense. A friend emailed me that she had dipped into a story and was struck by its “stateliness” – the way it feels of a different time. But I think it can speak to today, that there are a lot of values underlying the politics that are as relevant as ever. They can learn about kindness as a set of actions that can be undertaken by children. There is a story called “Kids,” by Mordkhe Spektor, about a time when Purim was less of a children’s dress-up holiday and more a holiday about charity. Two boys who are best friends go around and try to raise money to buy shoes for the granddaughter of an old water carrier who is living in poverty.

Nobody anticipates a book being released into a pandemic, but I’m hoping families who are home a lot together and who in some ways have gone back to old-world baking and gardening might go back to an old-fashioned practice like reading these stories aloud to one another.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.