(JTA) — Eliezer Papo, a professor of Sephardi and Hebrew literature at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University, has spent much of his career studying reinterpretations of the Haggadah — the seder liturgy text retelling the story of the Exodus — and how they reflect changing Jewish self-conceptions of religious and political identity.

“The Haggadah is well-known and a very flexible story, with a clear good and evil,” Papo says. “You just need to say in a humoristic way who is Moses, and then everyone knows who is Pharaoh.”

The tradition of these sacred parodies begins in medieval Spain as a fusion of the Christian springtime carnival with the Islamic literary and musical patterns. Following the expulsion of Jews in 1492, Haggadah parodies became a vehicle for Jewish communities in the Sephardi diaspora to satirize contemporary problems they faced internally and externally. For example, a Haggadah parody written in Smyrna in 1919 following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire described how the Jews came to Turkey and prospered, but then a new sultan arose who abused the Jews and suddenly the promised land became the West. Another parody from New York in 1923 decries price fixing by Big Matzah before the holidays.

Having grown up in the Jewish community of Sarajevo, Papo now works with his students to preserve the rich tradition of Haggadah parodies in Ladino, the lingua franca of Sephardi Jews for centuries, which he speaks fluently. This year they produced Agada de la Corona as an artifact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Riffing on the traditional seder text, the Corona Haggadah refers to “Rabbi” Albert Bourla, the Greek-Sephardic CEO of Pfizer, and relates how “the great Salonikan Jew liberated us with a strong vaccine in our outstretched arm. Had it not been for that, our children and their children would still be wearing masks.”

Papo’s academic interest in Haggadah parodies began in his hometown with the Sarajevo community’s unique Passover tradition of reciting the Partisan Haggadah, a little-known parody written by a communist Yugoslav partisan in 1944.

“This is the bread of affliction that the Jewish partisans ate in the Croatian forests of Kordun and Banija,” the Partisan Haggadah begins. “This year we are here, but next year, inshallah, we will drink raki in Sarajevo.”

First written and performed on Passover 1944 by a young Yugoslav partisan, Shalom “Shani” Altarac, the Partisan Haggadah is rooted in the bloody struggle by communist partisans against the Axis powers occupying Yugoslavia and their locally established puppet regimes.

Altarac was a talented musician and jokester from a Sarajevan family of prominent hazzans, or cantors. He was in charge of entertainment among the partisans, as well as being an active fighter himself (imagine Bob Hope’s USO show performed by Che Guevara). He accompanied his musical reinterpretation on guitar around a campfire as the partisans camped in the remote forests of Croatia with guns still loaded. He set his original parody to the same tunes as the regular Haggadah. (Listen to Altarac play it here.)

“Rabbi Gamliel said, one who does not speak of these three things has not fulfilled his obligation of Passover: salt, fire, and machine guns!” one lyric goes.

A group of Jewish civilians and partisans in Croatia, 1942. (Courtesy of Eliezer Papo)

Altarac was a member of the Rab Brigade, 24th division of the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Army Partisan Detachment. Its 250 Jewish members included many teenagers. They hadn’t been home in three years, having previously fled Bosnia, been interned by the Italians in Croatia and escaped an Italian detention camp on the island of Rab. They crossed the mountains through territory controlled by the Chetniks (Serb monarchists who fought against both Nazis and communists, but who were not particularly anti-Jewish) and joined the armies of Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the communist revolutionary who would go on to serve as president of postwar Yugoslavia. Nearly 5,000 Jews (10% of the entire prewar Yugoslav Jewish population) joined the partisans, rising easily in the ranks due to a lack of institutional anti-Semitism.

The partisans not only defeated the Axis armies who vastly outnumbered them, but went on to create the government of their newly free country. The victorious Jewish fighters were absorbed into the national founding mythology as larger-than-life heroes.

In his forthcoming book, “Fighting, Laughing and Surviving: The Story of the Partisan Haggadah, a Passover Parody Composed during the Holocaust” (Wayne State University Press), Papo describes the importance of the document to the partisans and their community in both preserving their story as well as highlighting the Jewish contributions to Yugoslavian nationhood.

Starting in the postwar years and still continuing today, the Jews of Sarajevo held the seder as a community. A cultural flourish like the Partisan Haggadah tied the ceremony together, making explicit the parallels of ancient Israelite and modern Yugoslavian liberation.

“Passover was both an important holiday for all Jews, and it fit beautifully with communism — celebrating the insurrection of proletariat slaves against the capitalist Pharaonic exploiters,” Papo explains. “You could be a proud Yugoslavian communist and a proud Jew and celebrate Pesach, no contradiction.”

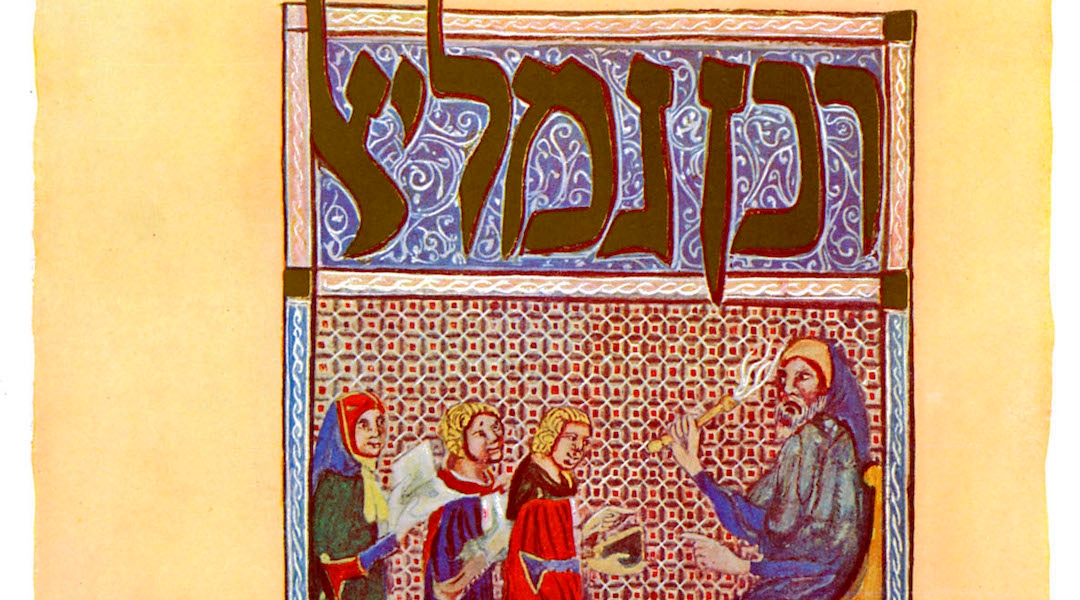

The Jews of Sarajevo had spoken and written in Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, since their arrival from Spain 400 years earlier. The illustrious Sarajevo Haggadah, an illuminated manuscript of the seder liturgy, and one of the oldest physical Haggadah texts still in existence, was most likely written in Spain in the 14th century and brought to the Balkans by the Sephardic Jews who fled the Inquisition for the comparatively tolerant Ottoman Empire.

For Passover, the traditional Haggadah was recited in Hebrew and then repeated in Ladino, the way American Jews recite it in English today. As secularization and assimilation have diminished the knowledge of Ladino in the community, the Haggadah is now also recited in Serbo-Croatian.

The Partisan Haggadah text incorporates all of these languages together. It begins by taking the Hebrew original and for each line offering an unrelated but humorous rhyme in Serbian:

Ma nishtana halaila (how different is this night)

ništa to ne valja (this whole deal is worthless)

hazeh mikol halelot (from all other nights)

Hitler je veliki skot (Hitler is a dirty animal)

The Dayenu in this Haggadah recounts not the Jewish people’s journey out of Egypt but the wanderings of the Jewish warriors through the hostile villages of the Croatian wilderness deeper into enemy lines.

We went to Topusko – dayenu.

To Ponikvar – dayenu

To Malicka – dayenu

To Petra Gora – dayenu.

Everything was all complicated and f**ed up

(zaguljenu i jebenu, rhyming with dayenu)

The partisan fighters were both idealistic secular communists and proud Jews — they valued and fought for both parts of their identity equally. As the Haggadah reads, “Beara de Israel bene horin, ad ki yoshienu haver Stalin” — “Next year as free Jews, once comrade Stalin delivers us!”

(This was shortly before Tito split with the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and while Stalin was still the standard bearer of international Communism. Ironically, Stalin was uncomfortable with Tito having Jewish partisan brigades.)

Unlike their Soviet neighbors, Yugoslav communists encouraged each nationality (what Americans would call ethnicity) to express and celebrate their cultures. Distinct populations of Croats (Catholic), Serbs (Orthodox), Bosniaks (Muslim) and others lived scattered in one another’s historic territory, sometimes even intermarrying. Despite ethnic rivalries, a shared secular nationhood united them. This multiethnic makeup made the Balkans an oasis of relative tolerance for the Jews. Until the war, Sarajevo had a substantial Jewish community of thousands who were never forced to live in a ghetto.

A page from the famed Sarajevo Haggadah, circa 1350. (Culture Club/Getty Images)

After the war, in the newly communist Yugoslavia, many Jews were members of the Communist Party. Religion was not banned, but party members — of any faith — were discouraged from attending services. Synagogue-based holidays like Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur were supplanted by “historical” and “ethnic” holidays, such as Purim and Hanukkah, that could be celebrated at home or as a community.

The Partisan Haggadah entered the Sarajevo community’s canon several years after the war. Altarac continued to write and entertain for Jewish holidays, writing yearly comedic musical revues for Hanukkah and Purim. At a communal seder in the early 1950s, some of his former wartime comrades encouraged Altarac to revive his old classic.

In a field interview quoted in Papo’s book, an elder recalls the performance:

“They said, ‘Shani, do you have your guitar? Why don’t you do your old Partisan Haggadah?’ He was unsure, a little shy, said it was improper, but they were all begging him. He said, ‘I’ll play just one stanza,’ took up his guitar, but of course once he started he did the entire thing. And by the end everyone was pissing on the floor, laughing their asses off.”

Until his death two decades later, Altarac’s yearly performance was the highlight of the communal seder. As the partisan generation slowly disappears, the youth have now taken it up, reciting “we were partisans in Croatia” the same way the rest of us recite “we were slaves in Egypt.”

Altarac’s work was a unique instance of a Holocaust survivor relating to his experiences with humor, for himself and his comrades. And it is the continuation of a longstanding Sephardi tradition of Haggadah parodies commemorating wars, although this is likely the only one to be written by a combatant and survivor during the war itself.

Papo has discovered dozens of similar texts from Europe, the Middle East and the Americas, with the earliest being from Curacao, the Dutch Caribbean colony, in 1778, and the most recent from the Israeli War of Independence in 1948.

According to Papo, “These stories have every social and political movement that a Jewish community ever identified with — socialist, capitalist, Zionist, anti-Zionist, Ottoman, American — all compared to the Passover story. This is exactly the purpose the Haggadah was written for originally — to shape and to construct a people’s identity anew in every generation, as if they left Egypt.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.