(JTA) — Like many people, I encountered “Maus” as a middle schooler. But unlike many people, I can say that it set me on a direct path to my eventual career — as a scholar of religion, especially Judaism, and popular culture.

I was 12 when the second volume of “Maus” was published, and I read both volumes in one long afternoon. It was the first graphic novel I had read, and like many 12-year-olds I was just starting to think of myself as a person able to have independent ideas and opinions. The very fact of “Maus,” the fact that I could hold in my hand something so simple and yet complicated, changed the way I thought about how we tell stories.

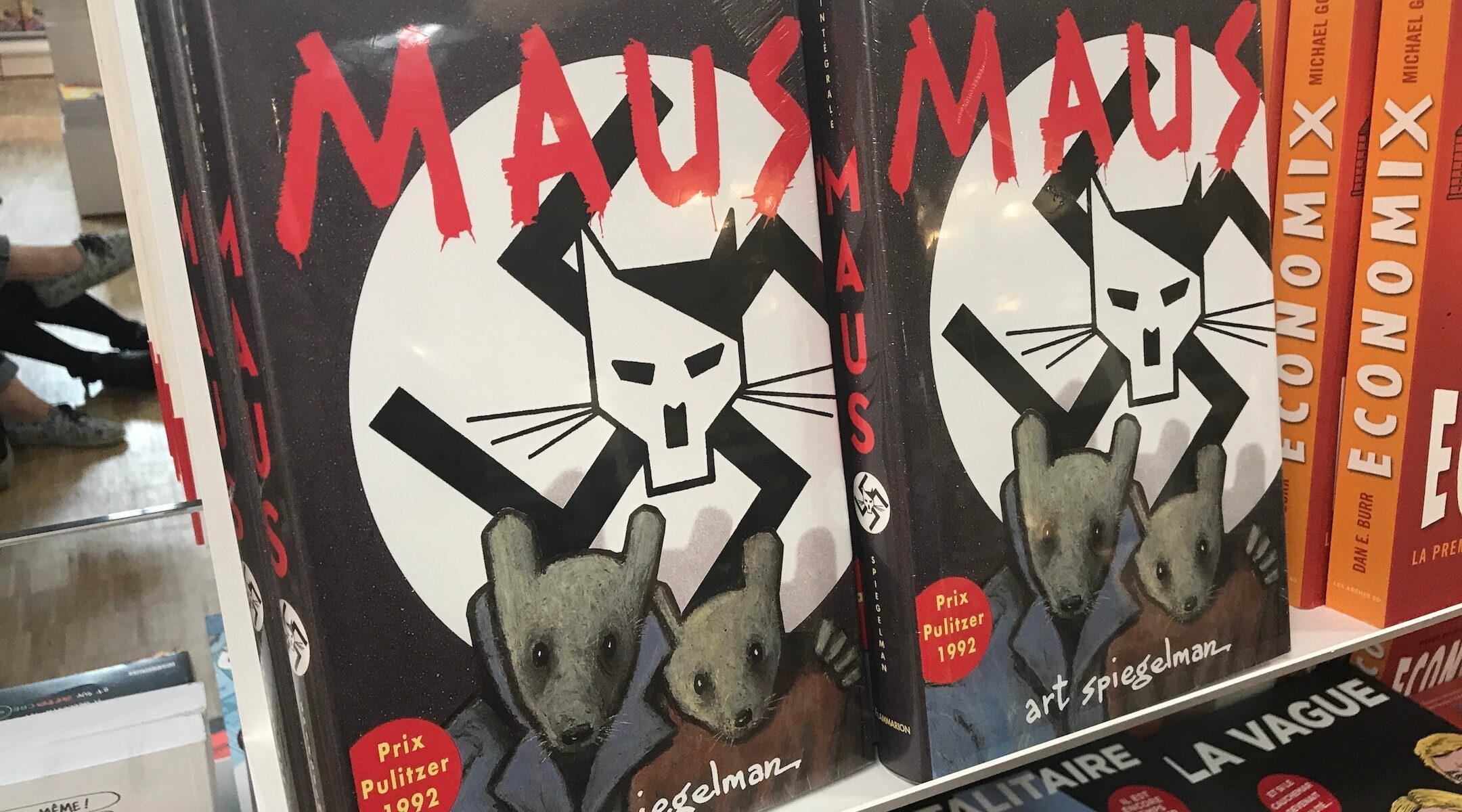

Art Spiegelman’s nonfiction graphic novel uses the conventions of comic books to tell the story of his parents’ experiences as Polish Jews before, during and after the Holocaust. It is also a second-generation story about the legacy of the Holocaust on Spiegelman, a survivor’s child. Spiegelman took a genre that many could not see as literature and turned it into a medium that could tell stories in a way no other book could. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then “Maus” may as well be Proust, because it contains words in the millions in under 300 pages.

In college I took a class on the Holocaust. I wrote my final paper on “Maus.” For my PhD comprehensive exams I needed to choose a text to study for one of my exams. I chose “Maus.” I had to convince people it was a worthy text, but convince them I did.

When I began teaching Jewish graphic novels I referred to the course as “The House that ‘Maus’ Built,” because I do not teach “Maus” in the course. Instead I teach about the entire industry built, in large part, on the legacy of “Maus.” The reason I feel comfortable excluding “Maus” from that syllabus is that every year, without fail, almost every student has already read it, many in an educational context. It is a modern classic. It prepares students to have so many important conversations and sets them up to jump into the canon of Jewish graphic novels.

This is why the McMinn County, Tennessee, school board’s unanimous decision to remove “Maus” from the district’s eighth-grade curriculum concerns me as an educator. A text that has had such a positive impact on untold thousands of students, and that I count on a plurality of my students to have encountered before they arrive in my college classroom, is under threat. The idea that with each passing year fewer and fewer students may not have had the chance to wrestle with “Maus” is deeply troubling. Having to begin the course with a basic introduction to sequential art and Jewish themes would cost not only time, but also the ability to engage in more sophisticated conversations. Having to catch students up on “Maus,” for me, would mean losing other extraordinary titles such as Joe Kubert’s “Yossel” or Amy Kurzweil’s “Flying Couch,” and would substantially change the narrative arc of the semester.

The McMinn school board says its decision was based on “rough language” and depictions of nudity. A great many mocking responses to this have pointed out that the characters in the book are anthropomorphized animals, including the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, who are depicted as mice. But it was not nude mice that spurred this criticism. The minutes of the school board meeting suggest that the images they’re reacting to are from the interstitial comic “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” an earlier Spiegelman cartoon that appears midway through the graphic novel and uses a different graphic idiom.

“Prisoner on the Hell Planet” was the initial comic Spiegelman drew to process his mother’s suicide, which its distraught narrator cannot separate from the horrors she endured under the Nazis. His mother died in 1968, when Spiegelman was 20, and he drew “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” in 1972. “Maus” was first serialized in 1980 and published in book form in 1986. The comic includes images of his mother slitting her wrists with a razor and of Anna Spiegelman’s naked body in a tub filled with her own blood.

This is not vulgar nudity — and the rejection of of the book based on these images suggests that the McMinn County school board has not understood what Spiegelman did with these books, or what it means to be ongoing witnesses to horror.

According to a taxonomy outlined by Scott McCloud, graphic novels can be “word-specific,” “picture-specific” or “duo-specific” based on what element of the page is carrying the information the reader needs to understand the story. The “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” section is particularly picture-specific. The pictures are the story. The story is the message. And the message is the teachable moment explaining what loss and grief and horror felt like to a child of survivors, showing readers emotions that words could never convey.

One of the low points of a meeting full of low points came when a school board member said, “It looks like the entire curriculum is developed to normalize sexuality, normalize nudity and normalize vulgar language. If I was trying to indoctrinate somebody’s kids, this is how I would do it.”

The idea that a depiction of the corpse of a young man’s mother is “sexual” says more about the school board member than it does about the book, and that he thinks such images are a way to “indoctrinate” children is the truly Orwellian element in this discussion. Allowing students to see visual representations of things that are fundamentally unspeakable is not indoctrination; it is good pedagogy and it is a validation of the big feelings that adolescents are having and are unable to articulate.

In “Regarding the Pain of Others,” Susan Sontag writes that photographs force us to face things we would otherwise try to minimize. Photographs do not allow us to hide from the reality of trauma, and — for some — the simpler and more straightforward the image the better. She writes that “photography that bears witness to the calamitous and the reprehensible is much criticized if it seems too ‘aesthetic’; that is, too much like art.”

“Maus” forces the reader to bear witness in a way no written account can, and the picture-specific portions of the book are especially good at forcing the eye to see what the mind prefers to glide past. “Maus” forces the reader to confront reality with increasing pressure — it begins with soft, color drawings of animals before it slaps the reader in the face with the Albrecht Durer-on-psychedelics black-and-white style of “Prisoner on the Hell Planet,” and ends with actual photographs of the Spiegelman family as a final reminder to the reader that these people lived and died in these terrible ways.

The decision by the McMinn County board members was wrong, and they have received plenty of criticism for it — so much so that they issued a statement clarifying that they do not oppose instruction about the Holocaust. But that doesn’t change the fact that they uncritically accepted as sexual an image that is undeniably not, and ignored how visual records of atrocity serve as some of the most powerful teaching tools available.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.