(JTA) – Danville, Iowa, may seem an odd place for a Holocaust museum — until one learns that in the spring of 1940, an envelope addressed to “Miss J and B Wagner” brought letters written by Jewish sisters in Amsterdam to sisters living on a southeast Iowa farm.

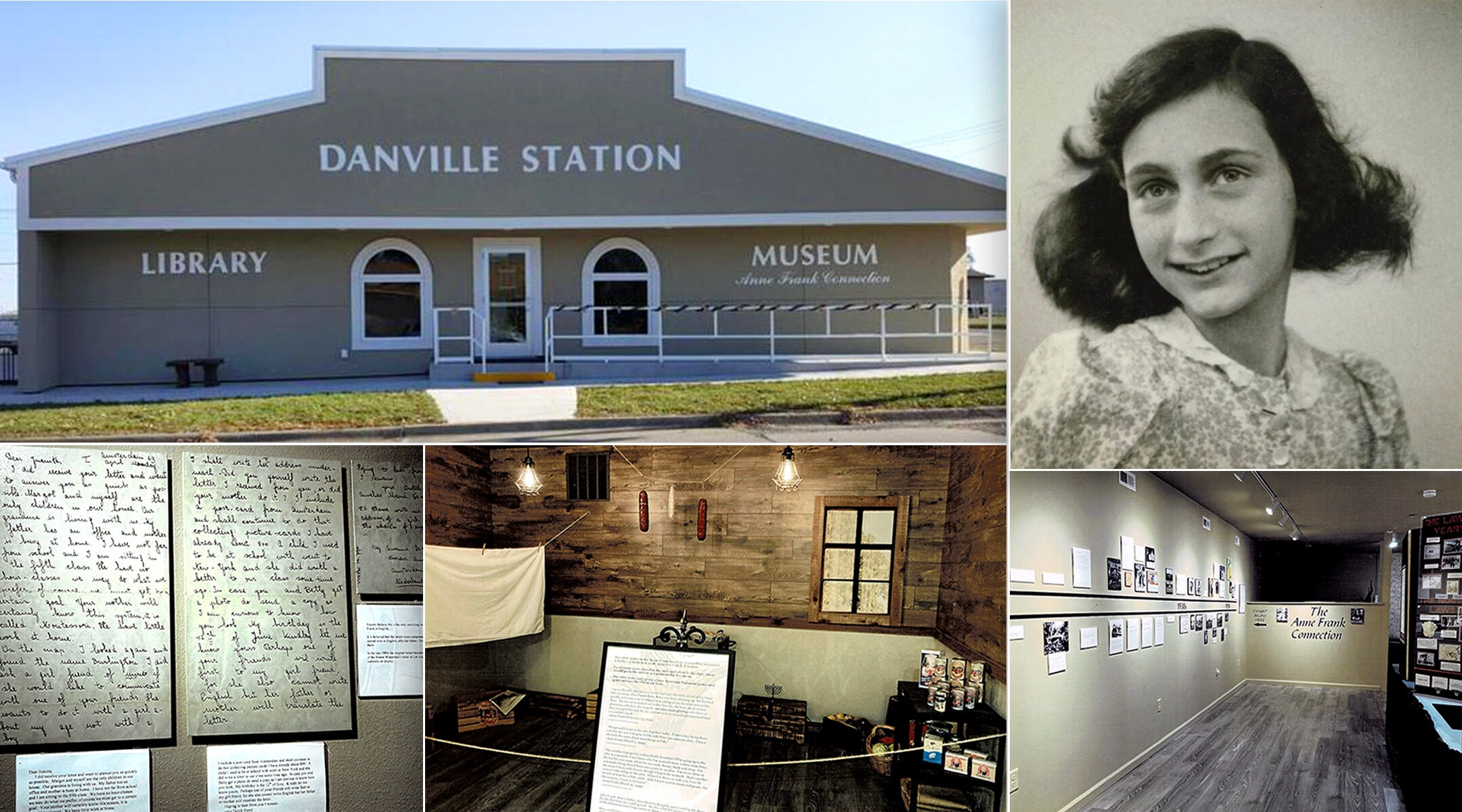

That correspondence — from Anne Frank to Juanita Wagner, and from Margot Frank to Betty Wagner — is the cornerstone of Danville Station, an off-the-beaten-path museum that tells a unique story.

Nearly all of the Holocaust museums and memorials in the United States are in cities or suburbs, usually with large or historic Jewish communities. Danville, 13 miles west of the Mississippi River, is an exception by its location, a population of fewer than 1,000, and that neither the Iowa Jewish Historical Society nor other state and county history groups cite any Jewish past in the town.

The town did have a teacher who wanted students at Danville Community School to understand that there was a wider world beyond fields of corn, oats and soybeans. Birdie Mathews enjoyed travel, in the United States and abroad, and along the way collected names for her “International Correspondence Program.”

In a videotaped 2008 interview on view at Danville Station, Betty Wagner recalled how the exchange of letters with sisters attending a Montessori school in Amsterdam was arranged. At the time, Juanita and Anne were 10 years old, while Betty and Margot were 14.

“The teacher asked us if we wanted to write to someone overseas. I can remember how excited we were. It would be a great thing to do… We wrote that we lived on a farm. We had cows and chickens and pigs. It was just friendly talk. We didn’t have television and sometimes we didn’t even have a radio. All we had was a little weekly newspaper that wasn’t very worldly. So, to write to somebody overseas was a great experience,” Betty said.

The envelope from Amsterdam brought letters and school photographs. “They were written in English,” Betty recalled. “We were pretty sure that they didn’t know English. But we were thrilled anyway. We sat down and answered them right away.” (The Franks’ father, Otto Frank, who had lived briefly in New York City, likely translated the Wagner girls’ letters into Dutch and helped his daughters reply in English, with occasional misspellings and lapses in syntax.)

Anne’s letter, dated April 29, 1940, is the kind a young pen-pal might write, describing life at home and school. “Your mother will certainly know this system, it is called Montessori. We have little work at home,” Anne told Juanita, who had mentioned that her mother was a teacher. Anne enclosed a “picture-card” of the Amsterdam canals, from her collection of about 800 such cards. The letter was signed, “your Dutch friend, Annelies Marie Frank,” her full name.

In her letter, dated April 27, 1940, Margot wrote about school and her winter recreation activities, but also current events. “We often listen to the radio, as times are very exciting, having a frontier with Germany and being a small country we never feel safe,” she said. To visit cousins in the Swiss city of Basel, “we have to travel through Germany which we cannot do or through Belgium and France and in that we cannot either. It is war and no visas are given.” She signed off, “With kindest regards your friend. Margot Betti Frank.”

Juanita and Betty wrote back, but never received a reply.

Not two weeks after Anne and Margot wrote their letters, Germany invaded the Netherlands. By June 1941, Jews were issued identity cards stamped with a “J.” That fall, Jews were required to attend separate schools. In late April 1942 came an order to wear a yellow Star of David with the word “Jew.”

After Germany’s invasion, “we feared that we might not ever hear from them again,” Betty Wagner said in the 2008 interview. “We never knew what was happening. Bombs were dropping. We didn’t know if they had enough to eat. But we always thought about them. We never forgot. They were very important to us.”

A notice ordering Margot to report to a German labor camp prompted the Franks’ move in early July 1942 into the “secret annex,” two floors and an attic in the rear of the building where Otto Frank had established the Dutch branch of Opekta, a company that sold pectin and spices. Co-workers risked their own safety by supplying food and necessities to the Franks and four others hiding with them.

The Franks were betrayed and, on Aug. 4, 1944, the Gestapo arrested the annex residents. From the Westerbork transit camp the Franks were transported by rail to the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. Two months later, Anne and Margot were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany.

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945, Betty wrote to the Amsterdam address. “I didn’t even know if they would get the letters or if they were still there. I had no idea,” she told the interviewer. “It took about three or four months and I got a letter back from their father, handwritten, five pages, telling about what had happened to them during the war. How they had hidden in the attic and how hard it was on Anne. I cried. We all cried.”

Only when Otto Frank replied in October 1945 did Juanita and Betty learn that 15-year-old Anne had died in Bergen-Belsen in February, after contracting typhus, and that Margot also died there that month, shortly before or after her 19th birthday. Otto survived Auschwitz, but his wife Edith died in January, likely of starvation.

And not until Otto’s letter did the Wagners learn that their pen-pals were Jewish.

Betty was living in California in 1956 when she heard a radio story about a Broadway play based on a book called “The Diary of Anne Frank.” She eagerly read the book and retrieved the girls’ letters from a shoebox; Otto’s had been lost. Betty told friends about the letters. Her financial advisor, who was Jewish and understood their significance, contacted a New York auction house.

In 1988, the letters were sold for $165,000 to an anonymous buyer who donated them to the Simon Wiesenthal Center. “Exact” reproductions are displayed at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. The originals are kept in a bank vault.

Juanita Wagner Hiltgen died in 2001 and Betty Wagner in August 2012.

Danville Station is the only institution to which the Wiesenthal Center has provided digital images and granted permission to display the letters.

The curator at Danville Station is Janet Hesler, a lifelong resident who retired after 30 years with the school district. Hesler traces her interest in the letters to newspaper articles about the auction in 1988.

“In early 2000 or 2001 Susan Goldman Rubin and Betty Wagner came to Danville to prepare for the writing of [Rubin’s] book ‘Searching for Anne Frank.’ I was working at the school then and I visited with them about local families to contact,” Hesler said.

The museum shares space with the town library in a renovated 1898 building (the oldest in Danville). The museum, which Hesler said “doesn’t really have a budget,” charges a $4 admittance fee ($2 for students). Rental income from a second-floor apartment covers the taxes and bills.

The guest book has been signed by visitors from 36 states, as well as the Netherlands, Israel, the Philippines, Australia, Japan, Russia, Canada, France and Egypt. As for the townsfolk, “I’m sure that I could knock on several doors in my general neighborhood and say, ‘Have you been to the museum?,’ and I bet they’d say no. Those areas close to home that you have, sometimes we don’t really appreciate them. The same is true with the museum,” Hesler said.

Two timelines run throughout the museum. The upper traces events in Europe (beginning with Otto and Edith Frank’s marriage in 1925) and the lower events in Danville, in Iowa, and in the United States.

A glass case displays items that Hesler’s father, Army Sgt. Robert Gerdes, brought home from World War II, including wooden clogs issued to Jews in the concentration camps when their shoes were confiscated. Gerdes, who was awarded a Bronze Star for his service in the Battle of the Bulge, entered the Dachau concentration camp the day after it was liberated by American forces on April 29, 1945.

“My mother said it changed him. He talked more in later years, before he passed, but it was always very emotional. He talked about the stench as they were marching and how they couldn’t figure out what it was. He talked about getting to Dachau and seeing people stacked up, he said just like cordwood. People were alive, crying. People were dead,” Hesler said, her voice breaking.

Just as a bookcase disguised the entrance to the Franks’ hiding place, a bookcase in Danville Station hides a hallway that leads to a replica of the attic in the secret annex, with boxes and food packages marked in Dutch and a replica of the window from which Anne could see a chestnut tree in a courtyard.

The museum also features prints of paintings created by friends of the Frank family. Erich and Fritzi Geiringer, and their children, Heinz and Eva, lived on the opposite side of Merwedeplein square from the Franks. Eva and Anne, born less than a month apart, were friends. To evade the Nazis, the Geiringers moved from place to place. Erich and Heinz painted while in hiding. Betrayed by someone they thought a friend, the Geiringers were seized on May 11, 1944. In the rail car taking them to Auschwitz, Heinz told Eva where to find 30 concealed paintings.

Erich and Heinz perished in Auschwitz. After Soviet troops liberated the camp in January 1945, Eva and Fritzi returned to Amsterdam and retrieved the paintings from beneath floor boards, along with a note that read “Property of Erich and Heinz Geiringer from Amsterdam who are in hiding and will collect the items after the war.”

The paintings are housed at the Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam. In conjunction with a 2012 Anne Frank exhibit at a Davenport, Iowa, museum, Eva Schloss (her married name) arranged for the Jewish Federation of the Quad-Cities to make the prints displayed in Danville. When Schloss visited in May 2018 she presented Hesler with items on loan: silverware embossed with the letter “F,” from the trousseau of Otto Frank and Fritzi Geiringer, who married in 1953, as well as Otto’s stationery.

In the future, Danville Station hopes to obtain and display a German rail car of the sort that transported Jews to the concentration camps.

Eighth-grade students in Danville study the Holocaust. As Anne Frank collected “picture cards,” since 2012 successive classes of 8th graders have collected postcards; their goal is 1.5 million, the number of Jewish children estimated to have died in the Holocaust. As of January, the collection numbered 28,165. (Postcards may be sent to: Danville 8th Grade Class, P.O. Box 304, Danville, Iowa, 52623.)

The effort is similar to the Paper Clips Project, in which middle-school students in rural Tennessee collected well in excess of their goal of 6 million paper clips to remember Jewish victims of the Holocaust, and the Holocaust Stamps Project at a Massachusetts charter school, where students collected more than 11 million postage stamps to represent the death toll of Jews and others.

The letters that Anne and Margot Frank wrote have been preserved, but what of the letters from the Wagner sisters?

Anne packed a bag as her family went into hiding. Anne wrote in her diary on July 8, 1942, “The first thing I put in was this diary, then hair curlers, handkerchiefs, schoolbooks, a comb, old letters; I put in the craziest things with the idea that we were going into hiding. But I’m not sorry, memories mean more to me than dresses.”

Perhaps the old letters included two written by girls from Danville, Iowa.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.