JERUSALEM (JTA) — I was on a short visit to Israel last week, and spent time with a friend with whom I have been engaged in a 30-year argument. Elli Wohlgelernter and I met when he was the managing editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and I was a staff reporter. We would argue about the future of Jewish life in the Diaspora, which even then he considered in unstoppable decline. We continued the argument after he moved to Israel not soon after.

Over the years we’ve both dug in our heels: I am convinced, even after living for a time in Israel, that aliyah is a happy choice but not the only defensible choice a Jew can make in the 21st century, and that Israel is not the sine qua non of global Jewish creativity — or inevitability — in the decades since its founding.

Elli is as convinced that the galut — the Hebrew term for exile — is doomed, physically and spiritually, as Jews assimilate into oblivion or face yet another cycle of historical persecution.

(Neither of us, I hope, is as tendentious or as boring as this sounds, at least not Elli, who is passionate about baseball, Jewish comedy, classic Hollywood and old-fashioned, ink-stained American tabloid journalism.)

Last week we picked up our old argument where we had left off. And thinking to give it a little fresh material, I suggested a visit to ANU-Museum of the Jewish People. The museum formerly known as Beit Hatfutsot opened on the Tel Aviv University campus in 1978, and recently underwent a major renovation and rebranding in order to convey “the fascinating narrative of the Jewish people and the essence of the Jewish culture, faith, purpose and deed.”

I remember visiting the museum in my 20s, when the old Beit Hatfutsot was about a decade old and still considered state of the art. There were dioramas depicting scenes out of various eras in Jewish history and an unforgettable display of models of synagogues throughout the ages. I also remember the criticism at the time: that the museum presented Diaspora Jewish life as a thing of the past. Its exhibit was organized according to “gates,” the last being the “gate of return,” with immigration to Israel presented less as a choice than a culmination.

Amir Maltz, the museum’s vice president for marketing, acknowledged that criticism when he met us in ANU’s lobby. “People from abroad would visit and say, ‘I don’t see myself here,’” as if their lives outside of Israel weren’t valid or vital. He suggested we start on the third floor, labeled “Mosaic,” which, he said, more than acknowledges that 50 percent of the world’s Jews don’t live in Israel and insists that there is no one right way of being a Jew.

And sure enough, the first thing you see are life-size videos of various individuals explaining their distinct versions of Jewishness. The walls nearby are lined with large-format photographs of various families: religious, secular and somewhere in between. There is a mixed-race couple, a same-sex Israeli couple and two heavily tattooed hipsters. It certainly represented the varieties of Jews I encounter in New York, and some of the exuberance seen in and around Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda market. The experts would call this pluralism, although it’s just the reality of who we are.

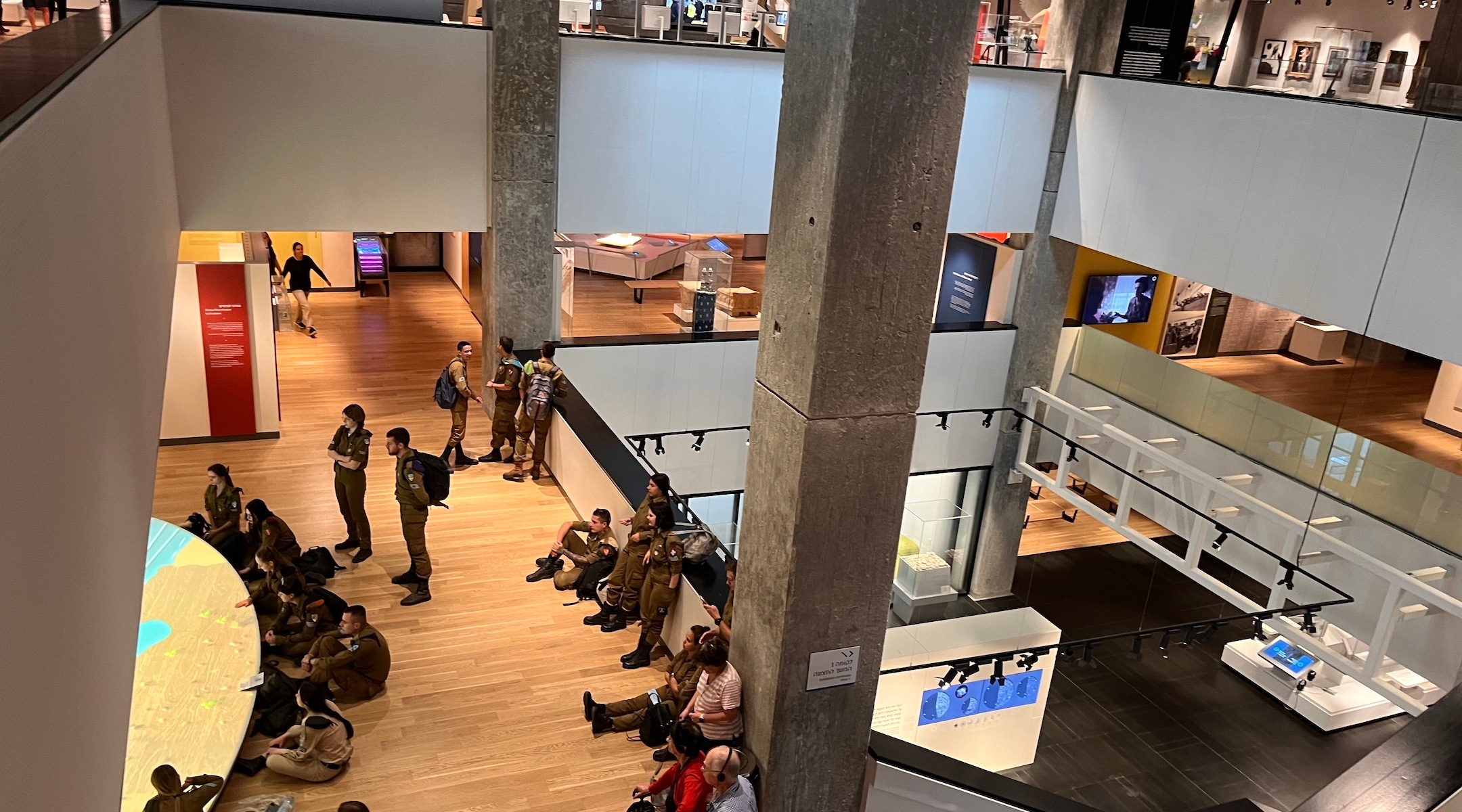

Israeli soldiers on an educational visit in the atrium of ANU—Museum of the Jewish People, which recently underwent a $100 million renovation, May 24, 2022. (Andrew Silow-Carroll)

Similarly, the second-floor history section begins with a wall title proclaiming “A People Among Peoples” — surely less Zion-centric than “A People in Exile” or “A People Dispersed,” two other plausible alternatives.

That history section was the least engaging to me, giving the vibe of an earnest middle school textbook trying a little too hard to make a long, twisting journey from Temple times to the present day palatable. I appreciated the balance the curators appeared to strike between the “lachrymose” school — Jewish history as a series of disasters — and the long periods of creativity, stability and autonomy enjoyed by Jews from North Africa to Middle Europe. The exhibit also tries hard to restore women to the Jewish story: I counted at least four main displays centering women.

But Mosaic, subtitled “Identity and Culture in Our Times,” was to me the most engaging of the three main permanent exhibits, and the one that succeeds the most in transforming this from a “museum of the Diaspora” to a museum of world Jewry. There are crowd-pleasing touches like a wall (and, on the first floor, an entire temporary exhibit) on Jewish humor (trust me, “Seinfeld” is as big a phenomenon here as it is back home), and the kinds of interactive features that I suspect are more intriguing to kids than adults. There is a wall dedicated to Jewish literature, from Cynthia Ozick to Clarice Lispector to the Israeli Nobelist S.Y. Agnon, and images of Jews in all their variety: Persian, Turkish, Brazilian and Canadian, to name a few.

One highly symbolic corner celebrates Yiddish, on the one hand, and the revival of Hebrew as a day-to-day language, on the other. My arguments with Elli are a recapitulation of the tension these languages represent. Israel’s founding generation was seen to look down on Yiddish, partly out of the expediency of nation-building and partly out of a none-too-subtle disdain for the Diasporic ways that Yiddish represented. The museum tackles this head on in one kiosk, asking “Who Will Reign in Zion — Hebrew or Yiddish?” and acknowledging how the debate often turned vicious and even violent.

There is also an animated film depicting Jewish literary, artistic and music greats accompanied by a Hebrew rap song about their accomplishments. I found it a little ironic that they chose a rap song — perhaps the popular art form with the fewest successful Jewish makers (and yes, I am aware of Drake). Then again, it was in Hebrew, and that kind of cultural synthesis — and, OK, flat-out appropriation — is part of the Jewish mosaic as well.

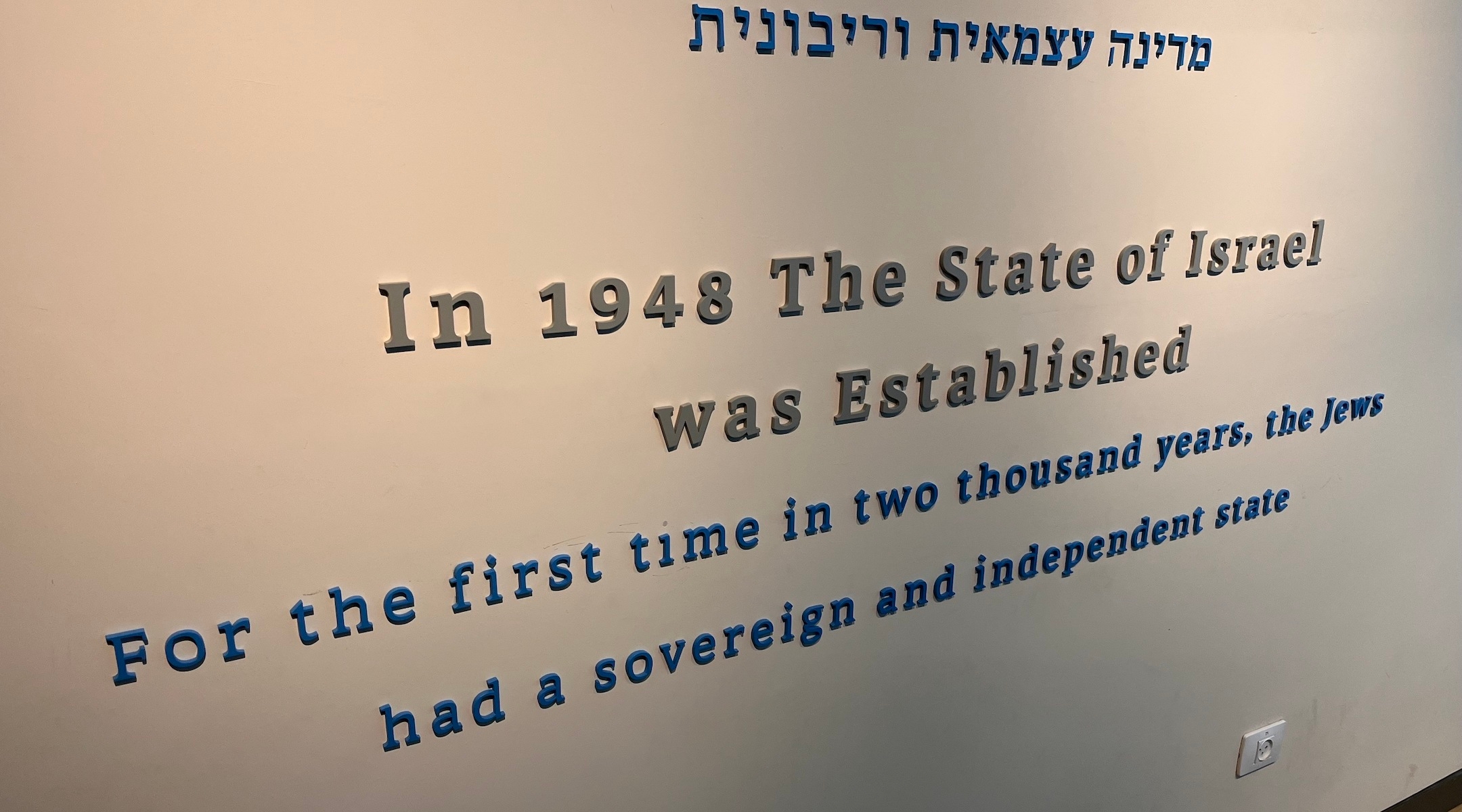

Like any effort to cram so many arguments and information in a limited space, the Identity and Culture section could feel a little thin. And yet for this Diaspora Jew, it also felt validating. I didn’t feel chided for living in galut, nor defensive about regarding Israel as just one of many paths in the Jewish journey. In the history section, Israel, like the Holocaust, is treated in just one room, this time with wall-sized videos displaying highlights of the country’s 74-year history.

An understated wall sign at ANU—Museum of the Jewish People is part of a room-sized video installation devoted to the establishment of the State of Israel. (Andrew Silow-Carroll)

Elli said the museum played fair in its presentation of the global Jewish story. “It didn’t celebrate Zionism nor diss Zionism,” he told me. “It told that story within the context of the history of the Jewish people.” But when I goaded him and asked if that was satisfying, he dropped the gloves: “One can walk away thinking that there are so many more chapters to write about the future glory of Diaspora Jewry, when in fact the story is virtually over. It won’t survive the 21st century.”

I left thinking that if the museum has a Zionist agenda, it doesn’t need a wall label or “gate of return” to make its point. You only need to exit the museum and find yourself surrounded by buildings representing the life sciences, engineering, biotech, security studies and “cereal crops improvement.” To catch the train back to Jerusalem, you walk along a bluff that offers a spectacular view of the high rises of Ramat Gan and downtown Tel Aviv.

And as you consider the present-day vitality or the nearly inconceivable accomplishments of the Jewish state, you think, “Touché, Israel. Touché.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.