UMAN, Ukraine (JTA) — As he jogged up a hill in this central Ukrainian town, a Hasidic man in a black knee-length coat flicked through a pocket prayer book. He was heading towards the one-story complex built atop a cemetery that houses the tomb of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. And he was late for a post-morning prayer celebration that involved music — including some klezmer-influenced saxophone — and rhythmic clapping.

It felt like a scene from just about any past Rosh Hashanah season in Uman, when the town’s Jewish quarter turns into a shtetl of sorts, hosting thousands of mainly Israeli pilgrims who belong to the Breslov branch of Hasidism. Rabbi Nachman encouraged his followers to visit his tomb for the Jewish New Year, and visit they have — in groups of varying size since his death in 1811, through various periods of 20th and 21st century upheaval. In 2018, over 40,000 Jews thronged the streets of Uman.

So far this year, it is estimated that 2,000 Hasidic pilgrims — overwhelmingly men, although some families visit as units — are already believed to be here, crowding into shoddy local apartment and hotel buildings. Some 8,000 more could arrive by the holiday, which begins at sundown on Sunday.

But this year has presented the pilgrims with an array of obstacles — all stemming from the ongoing war that has made Uman a danger zone.

A man plays a saxophone at a gathering in Uman, Sept. 19, 2022. (David Saveliev)

Ukrainian officials have urged Jewish pilgrims to not come, warning that any mass gathering in Uman, which has been struck multiple times since the start of the war, could become a target for Russian attack. U.S. embassies in Israel and elsewhere put out a striking warning that urged people who decided to go anyway to “draft a will.”

By now, some areas in the Jewish quarter seem to have more armed police than Jews. A JTA journalist who arrived on Monday was only able to move around under the observation of two heavily armed minders.

“It is clearly not the best time to come,” Ukraine’s Minister of Culture Oleksandr Tkachenko told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “A better time will come after our victory.”

Nevertheless, when interviewed by the JTA, some pilgrims preparing to leave for the trip from the heavily Orthodox town of Monsey, New York, and some of those already in Uman either nonchalantly laughed at the warnings or responded to them with righteous indignation. The potential of a missile attack seemed to be a relative afterthought for most.

The town’s apartments and hotels are old, cramped and shoddily built, but they fill to capacity during a normal pilgrimage season. (David Saveliev)

“My mother was afraid,” said Moe, an 18-year-old from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, who like several others did not give his last name for privacy concerns. “There was no other option for me. I was not afraid to come, because everything — my health and my wealth — depends on me being here at Rosh Hashanah.”

On a recent weekday, outside the grave complex — which also contains a synagogue and several other rooms — bearded Israelis in hoodies hung around smoking and sipping tea under a drizzling rain. When asked whether the potential dangers caused by the Russian invasion had made them consider skipping Uman this year, there was bewildered chatter.

“This is my rabbi,” protested Avi Koller, a 49-year-old Jerusalemite. “It is like when they told Jimi Hendrix that he was going to die from drugs. Jimi Hendrix replied that while he could die from drugs, he could also be hit by a bus tomorrow. We can die from anything.”

Koller, a former rocker who said he found religion late, took another drag on his cigarette.

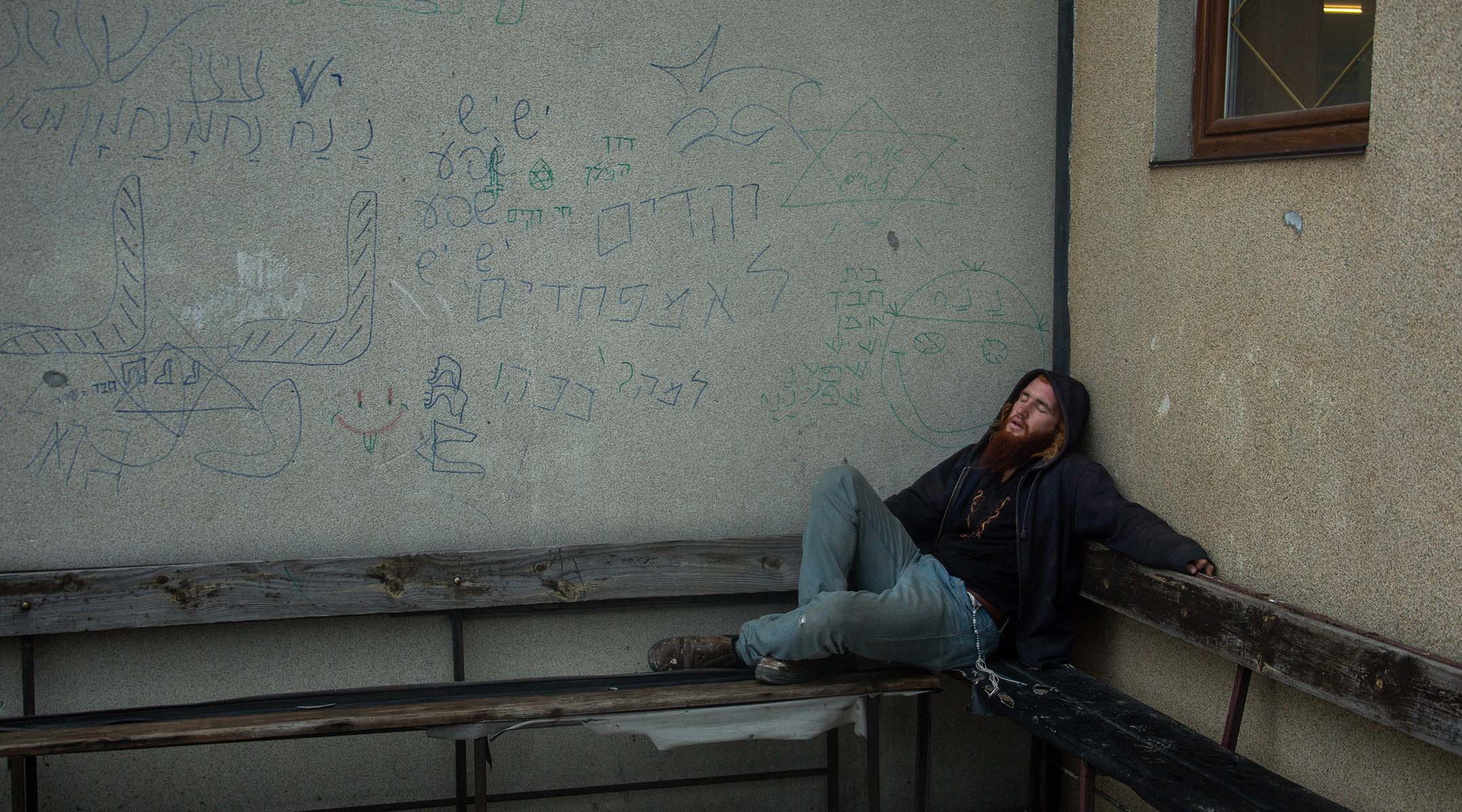

A pilgrim gets a nap in. (David Saveliev)

“Anyway, do you see any Russian missiles? Everything is fine here. In the evening, we have our curfew, from 11 to 5, and that is it,” he said.

But the journey has not been easy for most this year. The pilgrims, who usually come to Uman via Kyiv, have had to make other arrangements. Many decided to come days or weeks early to ensure that they were in Ukraine come what may. Since direct flights to Ukraine have been canceled, most are flying to Poland, Romania and Moldova, before hopping in taxis for expensive rides across the border. Some have stopped for a respite in a western city like Lviv; the journey from western Ukraine to Uman can then take up to 10 or more hours.

In some Breslov Telegram channels, which have been abuzz with requests for advice, users continually comment on an endless stream of photos of Turkish Airlines and El Al tickets to Chisinau and Bucharest, all being resold at exorbitant rates. Travel agents offer “once in a lifetime” offers for $1,000 tickets for flights and transport.

“When the war started, the only question I was asking myself was how I would get to Uman. All I knew was that for sure I would have to get here,” said Binyamin, 27, who said this year is his 20th time spending Rosh Hashanah in Uman. “I came through Romania. I landed in Bucharest and took an 18-hour taxi ride here.”

He spent $800 on his flights. “If you come earlier,” he said with a smile, “it is cheaper.”

On Monday, Ukrainian officials said they would be increasing security checks around Uman and redoubling efforts to explain the wartime rules — such as a strict curfew and a restriction on taking photos of military personnel — to pilgrims arriving from Israel. There is much skepticism on the ground that the guidance is needed or will even be imparted.

The town has upped its police presence as the pilgrims continue to make their way in, often by bus or taxi from neighboring countries. (David Saveliev)

“I haven’t seen anyone come to explain anything yet,” says Bernard, 25, from Borough Park in Brooklyn. Men pushed past him in a hallway inside the grave complex to collect their coats and hats after morning prayers had finished. “I don’t think that they need to come and explain anything anyway.”

“The war is eight hours away from here,” he added, referring to the fact that Ukrainians are currently in the middle of a successful operation to push the Russians back to the east. “In Israel, everyone lives much closer to the areas where the missiles fall from Syria or from Gaza than here.”

There is also a perception that the past two pilgrimages, which took place during the start of and then a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, had prepared many for the logistical difficulties of getting to Ukraine in a crisis.

“We all came early last year because of COVID,” said Bernard. “They wanted to close the borders, so everyone came early. We came months before, two years ago, when corona started.”

Despite the enthusiasm of those who have made the trek, the overall number of pilgrims is way down. In 2018, when 40,000 Jews filled every available bed — from hotel suites to hostels in damp Khrushchev-era apartment buildings — Mikhail Pinto was charging $5,000 for four days in one of his rooms in the large hotel he owns on Pushkin Street, the main drag that runs through the Jewish quarter. This year, that rate is down to $1,000.

A banner reads “We are praying for peace in Ukraine” near the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, the site that the pilgrims have to come to see. (David Saveliev)

“Business is very bad,” Pinto, an Israeli, said with a sigh, offering up a shot of whiskey to a table of visiting Jewish guests from Kyiv in the restaurant of his hotel. “During COVID, at least there was business, there was a big Rosh Hashanah. But now, there is nothing.”

He has noticed a steep drop in people coming from New York specifically.

“Americans and Canadians … they can’t get the proper insurance,” he said. “For Israelis, this isn’t so much of a big deal, but for Americans, it has been a huge issue.”

Overcoming obstacles to the pilgrimage has become ingrained in the collective myth of those who come to Uman. During the 1930s, when access to Uman was strictly forbidden to Jewish pilgrims, they secretly visited apartments near the cemetery where Rabbi Nachman was buried under the threat of arrest and deportation to Siberia. The Soviet Union then tried to stamp out the pilgrimage as part of its atheist agenda, but by the late 1940s officials relented to allow tiny numbers of closely watched Soviet Jews make the trip.

(David Saveliev)

It was not until the Soviet Union began to liberalize under Mikhail Gorbachev that it began to reopen access to Uman for the vast majority of Breslov followers who lived in Israel and the United States. In 1988, some 250 visas to visit Uman were granted.

This year, both Ukrainian and Israeli officials are clearly frustrated at the steadfast insistence among many Israelis, who make up roughly 90% of those who make the pilgrimage to Ukraine. The Israeli government has opened discussions with some Breslov leaders to encourage them to take a clear stance against coming, but officials have clearly been disappointed with the response, as few have chosen to echo these messages with any urgency internally.

Many pilgrims have also already run afoul of the wartime restrictions that are in place across Ukraine. In Ternopil, in western Ukraine, a group of pilgrims were arrested after hanging around and taking photos of a Ukrainian military checkpoint. Many others have been stopped for not taking the strict curfew restrictions seriously.

“It is dangerous. It is a risk. There is nothing that we or the Ukrainians can do to help protect you,” said Michael Brodsky, Israel’s ambassador to Ukraine. “The Ukrainians are using all of their efforts to fight the war and they don’t have the bandwidth to deal with the problems of tourists coming.”

David Saveliev contributed reporting.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.