(JTA) — Today is an unusual day on the Jewish calendar, which falls on the 10th of Tevet. Not only is it one of the fast days mourning the destruction of the Temple, but it is also a communal day of saying Mourner’s Kaddish.

This practice was instituted by the Chief Rabbinate of Israel in 1951, following the Holocaust, to offer those whose family members died — but it was not clear when — an opportunity for a specific day of mourning. These practices include lighting a yahrzeit candle, learning Torah in their memory and saying Mourner’s Kaddish.

Currently, the Jewish people are living through a horrible moment. We are praying for the return of the hostages in health. But every day brings new announcements of those who were killed — and the day of their death is not known.

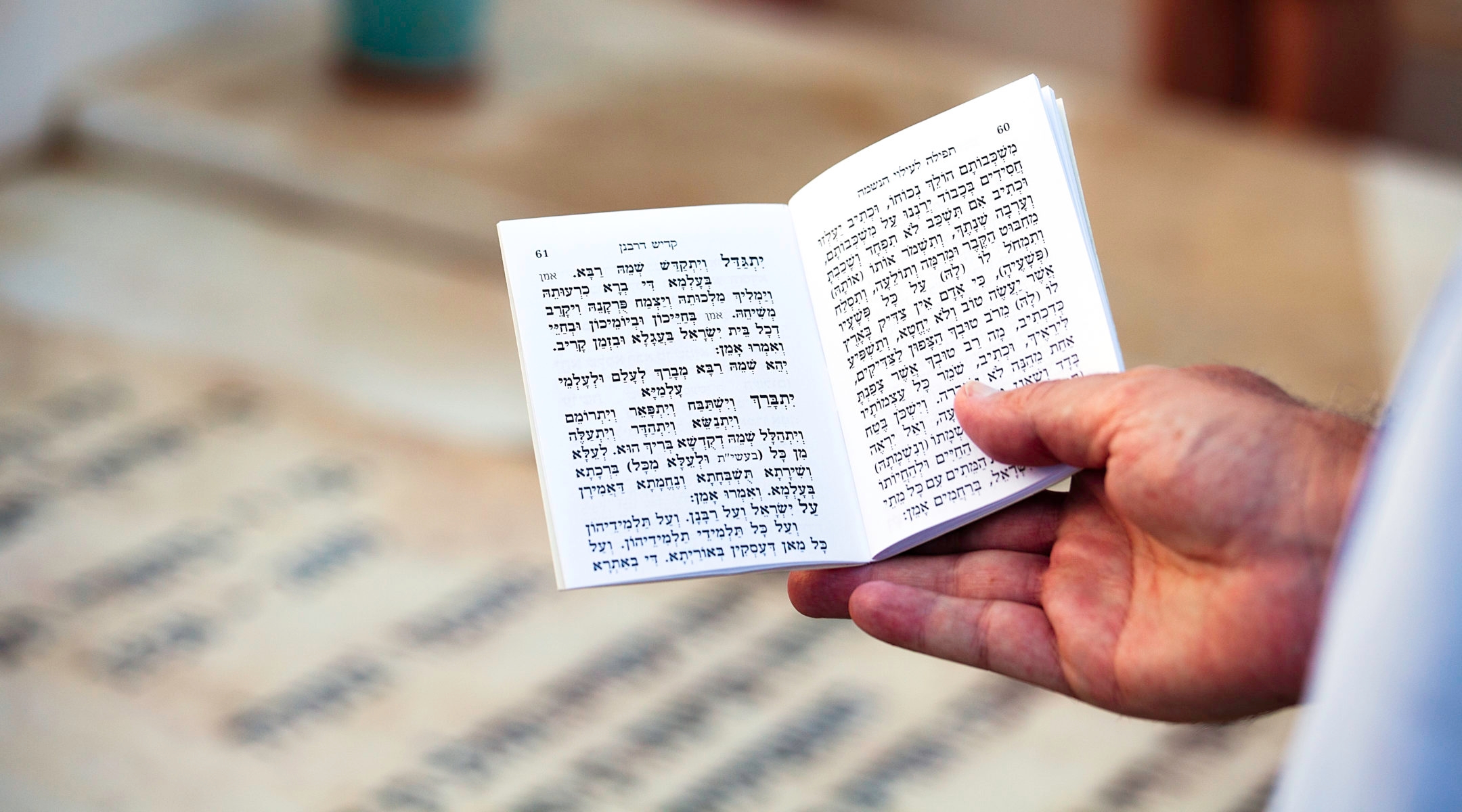

It is worthwhile then, on this day, to really understand the nature of the Kaddish. Is this really a prayer that comes to praise God’s name, as might be implied by the opening words: “Magnified and Sanctified Be [God’s] Great Name”? And if so, why was it a prayer assigned for mourners to say?

There are two main phrases that are key to understanding the Kaddish. By looking at them closely, we can transform our understanding of the prayer — from a testimony to faith in a God whose actions cause us to suffer for reasons we don’t understand to a prompt that reminds God of the brokenness of the world.

The first key phrase is that opening line: “Yitgadal Ve-Yitkadash Shemei Rabbah.” It is understandable how this could be seen as a prayer praising God. But the prayer is not a praise; it is a request. The worshiper is asking for God to be magnified and to be sanctified, implying — correctly — that God is not magnified and sanctified right now.

How could it be that God is not magnified and sanctified now? It is clear from the biblical context of this line in Ezekiel 38:23 that God will only be made great and holy at the end of days, when all nations recognize God as the supreme moral force in the world.

In a world of death and mourning, it is clear that God is not fully holy, or great. This prayer — put in the mouth of the mourner — begs God to speed the day when God is, in fact, great and holy. But it acknowledges that we aren’t there yet.

The other line in Kaddish that is critical is the congregational response: Y’hei Sh’mei Raba M’varach L’alam Ul’almei Almaya. The translation: “May His great Name be blessed forever and for all eternity.” A very strange feature of the Kaddish is the lack of God’s name. Almost all other prayers mention God’s name — so why is it missing from this particular prayer?

The answer has everything to do with the radical theology of the Kaddish. This is a prayer that is acting out the reality we live in: a world in which God’s name is diminished. And while we want God’s name to be magnified and sanctified, and we ask for that in this prayer, we still live in a world where that hasn’t happened fully. This is made clear through the death we are mourning, the death that occasions the recitation of this prayer.

This is illustrated in one of the oldest stories about the Kaddish, in the Babylonian Talmud , which is the source of this line of the prayer:

Rabbi Yose said: One time I was walking on the path, and I entered a ruin from one of the ruins of Jerusalem in order to pray. Elijah of blessed memory came and watched the doorway until I finished my prayer …. he said to me … :

“Whenever the Israelites go into the synagogues and schoolhouses and respond: ‘May His great name be blessed,’ God shakes His head and says: “Happy is the king who is thus praised in His house! Woe to the father who had to banish his children, and woe to the children who had to be banished from the table of their father!” (Brachot 3a)

This source offers another perspective on the context of the congregational response. On the one hand, when the phrase is recited by Israel in the synagogues and study houses, God is filled with happiness. But immediately following this statement of joy, God goes on to say: Woe is Me and woe is Israel.

The source reflects the complex emotions that are embedded in the recitation of the line. This is a line that was associated with the presence of God; reciting it meant that God’s name — the embodiment of God’s immanence — was at hand. Yet it is recited not in the world of the Temple and the High Priest, but rather in a world in which Jerusalem is in ruins.

In other words, the line has morphed from a reaction to God’s presence to a painful reminder of God’s hiddenness. God is no longer available in this world in the way God once was.

The Kaddish is not a stoic praise of an unfeeling God who for reasons we can’t know let our loved ones die without remorse. Rather, it is a plea for a better world in which God is more fully holy, and the presence of God more completely experienced.

We are not living in that world, and the Kaddish knows it; but it offers us a path to imagine a world beyond our current one. And critically, God is in league with us in begging for that world to come soon.

On the Day of Communal Kaddish 5784, at a time when it is clear we are not living in an ideal world, when the difficulty, pain and mourning that is found in every household, village and city, let us recite and respond to the Mourner’s Kaddish as a prayer, a call, and even a demand, that a better world come our way — speedily.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.