In his 2012 book, “Pox,” historian Michael Willrich looked at the politics of vaccination during the last great waves of smallpox in the United States. That’s when he discovered the case files of Harry Weinberger (1886-1944), a young, idealistic attorney who not only represented parents who refused to get their children vaccinated, but defended two of the best-known and most notorious anarchists of the early 20th century: Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

Along the way, the little-known lawyer (who lacks even a Wikipedia entry) pioneered the field of civil liberties law.

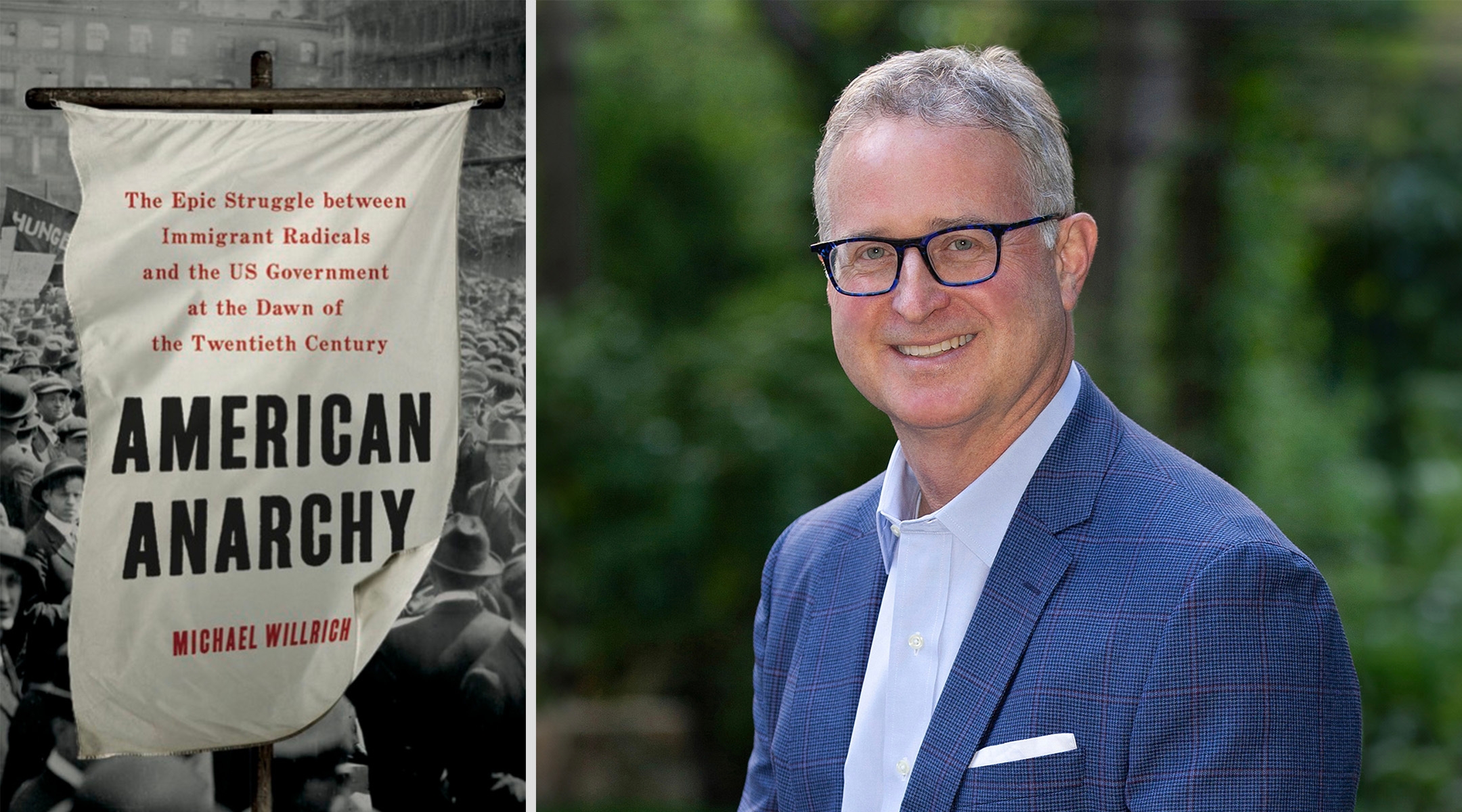

In his latest book, “American Anarchy: The Epic Struggle between Immigrant Radicals and the US Government at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century” — last month named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in history — Willrich chronicles how, starting in the 1880s, the government launched a decades-long war on anarchy and radicalism, involving spying, censorship and deportation, which laid the foundations for the modern surveillance state.

It’s a “war” often told through the stories of the government officials who carried it out: Anthony Comstock, the puritanical New Yorker who helped make birth control a federal crime; Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who in 1920 rounded up thousands of suspected anarchists on dubious charges; and a young J. Edgar Hoover, the future FBI chief who cut his teeth by disrupting and prosecuting radical networks.

But Willrich adjusts the lens to focus on Goldman and Weinberger, two Jews who made civil liberties their common cause despite her anarchist views and his almost spiritual belief in the authority of the Constitution.

“One of the central animating ideas in the book is the relationship between the anarchist movement, which defined itself as against the rule of law, and how anarchists became so enmeshed in the American legal system, and actually made some contributions to our legal culture today,” Willich told me in a recent conversation. “My larger interest is in what I call ‘speaking law to power’: using legal language, practices and strategies to challenge the growth of state power.”

“American Anarchy” is also a lively portrait of a period of American upheaval, with violent clashes between unions and management, and immigrants crowding rallies and reading publications that forced a nervous establishment to try to limit free speech and deport “anarchist aliens” like Goldman and Berkman, her erstwhile lover and lifelong collaborator.

At the center of the story is Goldman — Russian immigrant, nurse, author, birth control advocate, pacifist, radical celebrity — and Weinberger, a son of the Lower East Side drawn by Goldman and Berkman, writes Willrich, “ever deeper into their network of mostly Jewish anarchists, labor radicals, and bohemians in New York.”

Willrich is the Leff Families Professor of History at Brandeis University. He and I spoke about why so many Jews were attracted to radical politics, how Goldman is misrepresented even by her fans, and the ways in which the clashes of 100 years ago relate to current debates over free expression.

The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

This is a very Jewish story. Tell me about the conditions that made anarchism attractive to Jews in this period.

In the late 1870s and ’80s, anarchism emerges as the radical edge of the American labor movement and in that period, most anarchists in the United States were of German American, Irish American or English descent. But with mass emigration in the 1890s, 1900s and 1910s, the United States becomes increasingly either Russian, Jewish or Italian. The conditions that encouraged Jews to think of their situation in radical terms included labor exploitation and vast disparities not just in wealth but in the power between industrial employers and their workforce. Most Jewish immigrants were in trades like the garment industry, where they were subjected to significant economic exploitation.

Michael Willrich is the author of “American Anarchy,” a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize in history. (Basic Books; Dari Pillsbury)

Anarchism competed for the affiliation of Jewish immigrants in places like the Lower East Side and later up in East Harlem. Most Jewish immigrants did not become anarchists. Many of them just sort of went about the business of preserving family and their Jewish life without regard to deep immersion in politics, but some became truly radicalized by their encounters with industrial America and with the police. Many joined the Socialist Party. This is a period when the police are brutally suppressing strikes and a significant number of the leading anarchist leaders during this period were Jewish.

Which also inspires an anti-Jewish backlash, certainly among law enforcement.

The files of the Justice Department during this period are filled with surveillance reports that are filled with antisemitic language. Some openly call Weinberger a “dirty Jew” and say that he should be handcuffed and deported even though he is an American citizen who believes in the Constitution above all else.

Emma Goldman is much revered today as a sort of a feisty activist and feminist matriarch. But I think your book is a reminder that she was significantly more radical than some of her modern-day fans either realize or acknowledge.

She’s a very attractive character to a historian because she’s not only incredibly smart and principled, she’s very literary. She seemed to know everybody and reached out well beyond the boundaries of the anarchist movement to forge alliances with affluent, liberal-minded people as well. But her beliefs were very radical. At the core of anarchism for Emma Goldman was the idea that real liberty was liberty unregulated by man-made law and that the government is by its very nature coercive and violent and unnecessary. These were the ideas she promoted through her little magazine, published in New York in the 1900s and early 1910s, called Mother Earth. They were the ideas that she spoke about in public forums across the United States, ranging from small halls to crowded venues on the Lower East Side where she spoke Yiddish or German. She believed that the state should not exist, that the rule of law was a sham, that capitalism was inherently violent, and that real liberty ought to be absolute in the individual. Social connections ought to exist through voluntary relationships and exchanges, and she believed in the total obliteration of all status hierarchies and lines of authority.

Harry Weinberger didn’t become an anarchist but rather a legal pioneer in defending civil liberties. What was the Jewish milieu that he came out of?

Harry Weinberger was American born and proudly so. His parents immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire; his father was a fruit peddler on Houston Street on the Lower East Side. He grew up in a series of neighborhoods in Lower Manhattan where he had everyday encounters with Irish gangs and a culture steeped in antisemitism. But he saw great things for himself. He read widely, like many other young first-generation Jewish Americans of his era. He took full advantage of the New York public schools and got a night law school degree at NYU with a really significant number of future civil liberties lawyers.

For Jewish Americans of that era, the law — the American scripture of the Declaration ofIndependence, the Constitution and the common law — became a source not just of professional opportunity and growth, but also a way to express ideas of justice. And it’s hard not to see this as a kind of displacement from more formal religious practices, of studying the Talmud. He finds in these legal texts an almost scriptural basis for an understanding of justice. What he had in common with Emma Goldman was a belief that justice required absolute liberty of the individual.

Would you describe him as a patriot?

Oh, very much so. He would describe himself as a patriot. When World War I broke out, he was part of the movement for immigrants and their children who sought to discard their hyphenate identity and to embrace Americanism. By the time of Woodrow Wilson’s 1916 presidential campaign, Weinberger was also a pacifist, and he was opposed to American entry in the war. But he really considered himself to be an American, through and through.

The scene at New York’s Union Square after a bomb exploded at a demonstration against unemployment, March 1908. The bomb was carried by a Russian immigrant, Selig Silverstein, who said he had recently been badly beaten by the police. One bystander was killed and Silverstein blew off his own hand. (George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress).

This is the tension at the heart of this book’s narrative, in which Goldman, Berkman and Weinberger all came to work together. All three were demonized by the Justice Department and by local police, who considered Harry Weinberger as dangerous a radical as Emma Goldman. He’s a constitutional true believer, and she believes that it’s all window dressing for capitalism, and yet they end up engaging in some very consequential battles for freedom of speech and for fighting deportation laws. Their relationship was pretty remarkable, and she was always disappointed that he didn’t convert to anarchism.

That relationship between Goldman and Weinberger — never romantic, unlike her early fling with Berkman — comes across as spirited, literary and even a little flirtatious on her part. How did you get inside their heads?

I really knew that I had a book when I was reading the correspondence between Goldman and Weinberger, written from the Missouri prison during her two-year term [starting in 1917] for her alleged conspiracy with Alexander Berkman to obstruct the military draft during World War I. She uses Weinberger as her go-between to all of her people around the country. You can see their relationship deepen, and also you can see her engagement with legal thinking and her insistence that Weinberger and others create a legal defense league to protect political prisoners and represent them in court. You can see an anarchist really embracing some very modern legal strategies that anticipate the kind of civil liberties organizations that would really emerge full force in the 1920s.

Their relationship is also very personal, especially when it starts to head towards her being deported. The poignancy of those letters really moved me.

Weinberger defended people who were hounded for their beliefs in anarchism and birth control, and their opposition to the military draft and compulsory vaccination. What’s the common thread among these very different kinds of ideas?

For anarchists, and for folks like Weinberger, freedom had to be jealously defended against what they saw as growing government encroachment on personal liberty. Just to simply tell working class people about techniques of birth control was illegal in the early 20th century. And if you put something in the mail about birth control it was a federal crime. Compulsory vaccination laws were relatively new during this period, and they also involved government interference with liberty and bodily integrity as Harry Weinberger would have seen it. And this was openly discussed in 1905 by the Supreme Court, in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, when the Supreme Court upheld the right of state governments to order people to get vaccinated.

Emma Goldman and her onetime lover and fellow anarchist Alexander Berkman, c. 1917–1919. (Wikipedia Commons)

Your book is in part about the rise of the American surveillance state, so I want to ask this in a very reactionary way. We know that some anarchists either called for violence or actually carried it out. Alexander Berkman shot and nearly killed industrialist Henry Clay Frick in an assassination attempt, and was involved in a bomb-building project in 1914 that ended up killing four people in an East Harlem tenement. The “Preparedness Day” dynamite bombing in San Francisco killed 10 people in San Francisco in 1916. Was the government wrong in surveilling and throwing the weight of the law against what today we would call terrorism?

It’s a very fair question. I don’t think it’s reactionary at all. But the extent to which the government went at every level to suppress anarchism was extreme, and, as I argue in the book, was as radical as anarchism itself, as radical a departure from traditional constitutional ideas and the idea of liberty in America. The police in New York City and other major American cities, the Justice Department and the immigration officials of this period pursued anarchists and other immigrant radicals with a vengeance, breaking heads at meetings and in places like Union Square. They suppressed anarchist publications, even when they did not advocate violence of any sort.

But the most strenuous use of government power to crush the movement was through the use of the immigration laws. In 1903, in the wake of the assassination of President William McKinley by a native-born American anarchist, Congress enacted legislation that banned the entry into the United States of non-U.S. citizens who subscribe to anarchist beliefs. By 1918, Congress had enacted a law that allowed for the deportation of non-naturalized, so-called “alien anarchists” in the United States. This is how Goldman and Berkman were eventually deported [to Russia, in 1919].

Should the police and the state have been seeking ways to protect innocent people from anarchist terrorism? Absolutely. On the other hand, the category of alien anarchist was extremely convenient for public officials that sought to get rid of or stamp out all kinds of radicalism within the labor movement, not just anarchists.

Your book arrives almost at the 100th anniversary of the Johnson-Reed Act, which limited the number of immigrants through a quota, targeting especially people from Eastern and Southern Europe. Was the xenophobia that’s a theme throughout your book a cause or a consequence of the backlash against radical politics?

I think both. Nativist ideas and politics were very much present from the start of the anarchist movement. For a significant period of time starting in the 1880s, anti-radicalism becomes the principal language of immigration restriction. But by the time of the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924, eugenics and the desire to make American culture whiter in a 19th-century sense superseded concerns about radicalism. Anti-radicalism was certainly not the only impetus for rising American nativism, but it was a powerful way in which American leaders defended closing the borders.

I was struck how immigrants become scapegoats for whatever is making Americans fearful at a given moment. So while today the biggest fear is economic displacement, 100 years ago it was racial displacement, and in the early 20th century it was fear of radicals or challenges to the industrial order. The stranger becomes a vessel for America’s anxieties.

Immigrants are some of the most marginalized people. There are a number of folks in the book who are really young, really poor. They are working 12 hours a day, in factories, they come home at night and read Tolstoy, they read Goldman and Berkman, they read [Russian anarchist Pyotr] Kropotkin. And when they meet amongst themselves and they publish leaflets and circulars protesting actions by the Wilson administration, they end up just getting crushed and sentenced to 15 to 20 years in prison.

On balance, did the Harry Weinbergers of this period leave a civil liberties legacy that’s robust today or has power shifted again to a state that has so many surveillance and legal capabilities behind it?

I’m not going to have a perfect answer to that. In the early 20th century, you can see the rise of both a modern surveillance state and a more liberal tradition of civil liberties — although civil liberties more narrowly circumscribed than Goldman would have wanted.

Your book was written well ahead of the last eight months, but I was reading it at the same time that police were breaking up pro-Palestinian encampments on college campuses. Did you see parallels or differences in this clash between the state and free speech or radical speech and the ones you describe in your book?

I haven’t fully sorted that out for myself, but I will say that there are resonances in that we still have extremely meaningful discussions about the boundaries of speech that cut to the very definition of American democracy.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.