Kinky Friedman, the cigar-chomping, mustachioed Texan country singer and mystery novelist whose body of work often seemed like the un-kosher marriage of the Borscht Belt and the Bible Belt, died June 27 from complications of Parkinson’s disease. He was 79.

As frontman for the flamboyant 1970s country group Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys, he was notorious for satirical songs such as “They Don’t Make Jews Like Jesus Anymore,” a raucous sendup of racism, and “Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in Bed,” which poked fun at feminism.

He could also turn serious, with songs dealing with social issues such as abortion and commercialism. His 1973 song “Ride ’em Jewboy” is a haunting elegy on the Holocaust, recorded by Willie Nelson and sung in concert by Bob Dylan. The lyrics transform cowboy cliches into a rumination on Hitler’s victims:

Now the smoke from camps a-rising

See the helpless creatures on their way

Hey, old pal, ain’t it surprising

How far you can go before you stay?

The Jewboys broke up in the mid-1970s and Friedman spent much of the next decade in a haze of drugs. In the mid-1980s he cleaned up and began writing a series of successful, raunchy, comic mystery novels whose main character is himself. He wrote more than 20 books, all on a manual typewriter.

One reviewer, the actress and author Fannie Flagg, described his writing as “Raymond Chandler on drugs, if Chandler had possessed a tremendous sense of humor.”

In 2006 he ran for governor of Texas, looking to unseat incumbent Republican Rick Perry in a bid that went from joking to serious. His campaign material included a 13-inch talking action figure and bumper stickers that read, “My governor is a Jewish cowboy.” His official campaign slogan was “Why the hell not?” He considered himself tough on immigration, pro-choice, anti-capital punishment and a proponent of alternative fuels.

In time, his campaign gathered force as a serious quest to shake up Texas politics, break down traditional party machines and reach out to a dramatically disaffected electorate.

“In the last election for governor, only 29% of eligible voters went to the polls,” Friedman, known as “the Kinkster,” told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s Ruth Ellen Gruber that year. “Seventy-one percent didn’t vote — they didn’t like the choice between paper and plastic.”

In the end, Friedman placed fourth in the six-person race, receiving 12.6% of the vote.

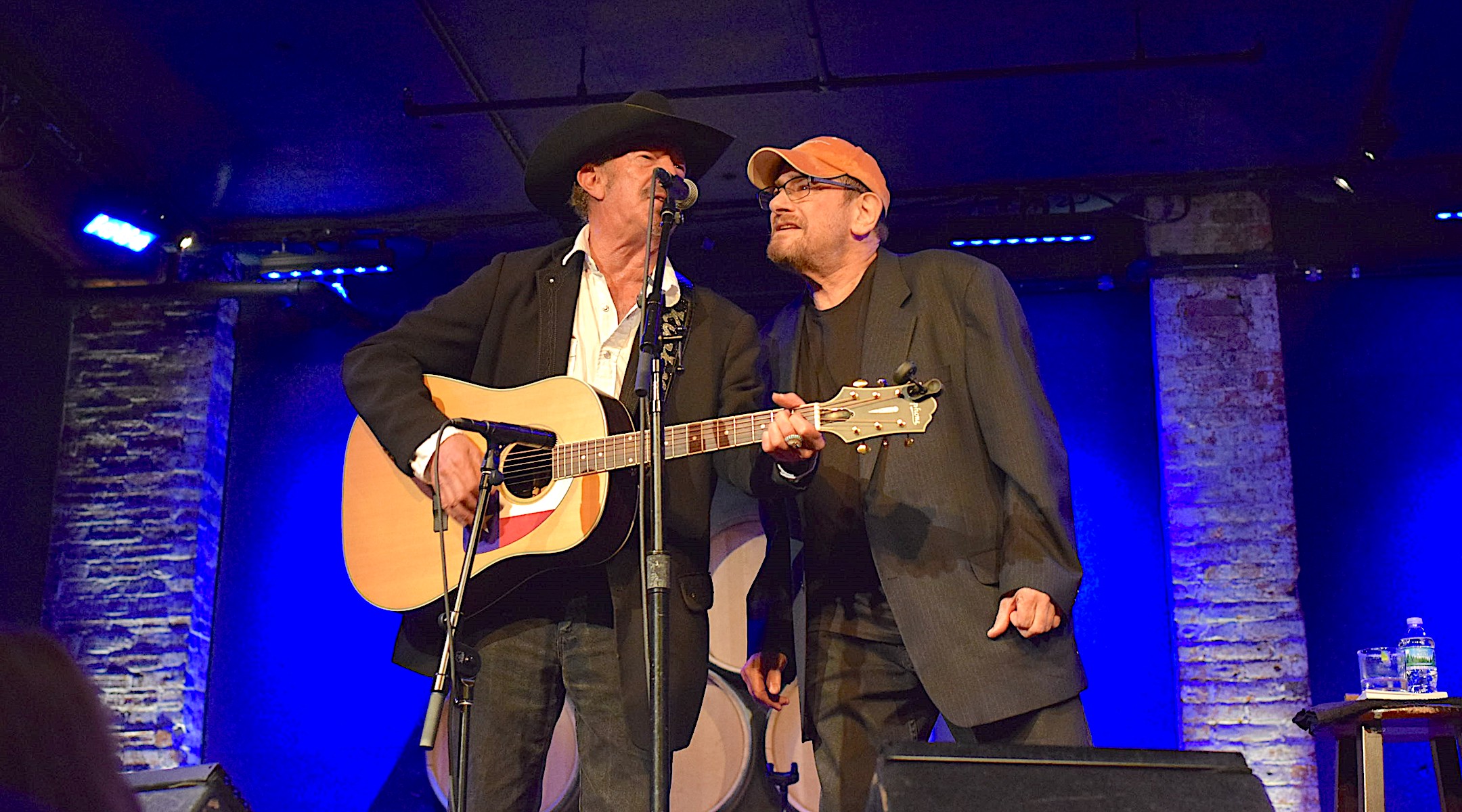

Nathan “Chinga” Chavin, right, and Kinky Friedman perform together in an undated photo. The two were frat brothers at the University of Texas. (Courtesy Brandi Chavin)

Born Richard Samet Friedman in Chicago in 1944, he moved with his parents to Texas as a baby and earned his nickname in college from his curly hair. His parents were educators who ran a summer camp for mainly Jewish children at Echo Hill Ranch, the 400-acre spread where Friedman would come to live in a small but rambling lodge.

“We had services every Friday night, and Kinky would play the guitar,” Ellen St. Clair, who spent four summers at Echo Hill, told JTA in 2006.

The property is also home to the Utopia Animal Rescue Ranch, a home and adoption center for abused and abandoned dogs that Friedman helped found.

He attended the University of Texas at Austin, where he majored in psychology. Friedman proudly recalled that during their time as members of the Jewish Tau Delta Phi fraternity he and a friend, Nathan “Chinga” Chavin, tried to admit African-American students, an effort that was ultimately thwarted.

After graduating in 1966, he served in the Peace Corps in Borneo. After returning from the Peace Corps, he formed Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys, at a time when hybrid “country rock” bands — including The Band, the Eagles and Buffalo Springfield — were rising up the charts. The Jewboys drew a cult following — and occasional protests, as when the National Organization for Women awarded Friedman its “Male Chauvinist Pig Award” in 1973.

In early 1976, he joined Dylan on the second leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue tour. Friedman claimed to have been the first “full-blooded” Jew to take the stage at the Grand Ole Opry.

Friedman would cite Mark Twain and the humorist Will Rogers as his heroes, and the inevitable comparisons were not far off.

“These days,” he once said, “there are many people around the world who listen to the songs that made me infamous and read the books that made me respectable.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.