In 1993 the film critic Shawn Levy was working on a biography of Jerry Lewis when, sitting down with the comedian on his yacht, Levy gingerly asked him about “The Day the Clown Cried.”

Levy knew the film, Lewis’ unreleased Holocaust movie, was likely to be a touchy subject for the legendary funnyman. Even so, the response was apoplectic.

“I’ve never been yelled at like that in my entire life,” Levy recalled to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency three decades later. He recited the string of insults the once astronomically popular Jewish performer threw at him for having the gall to inquire about the movie: “‘You need a personality transplant. You’ve got some nerve.’”

Finally, in an epilogue that became so famous in comedy circles that Martin Short would later reenact it for dinner guests, Lewis ordered Levy off his yacht. The star also demanded the author’s tape recorder, then erased everything related to discussion of the film that he directed and starred in before sending it back to his biographer. That meeting, Levy’s second with Lewis, would be his last.

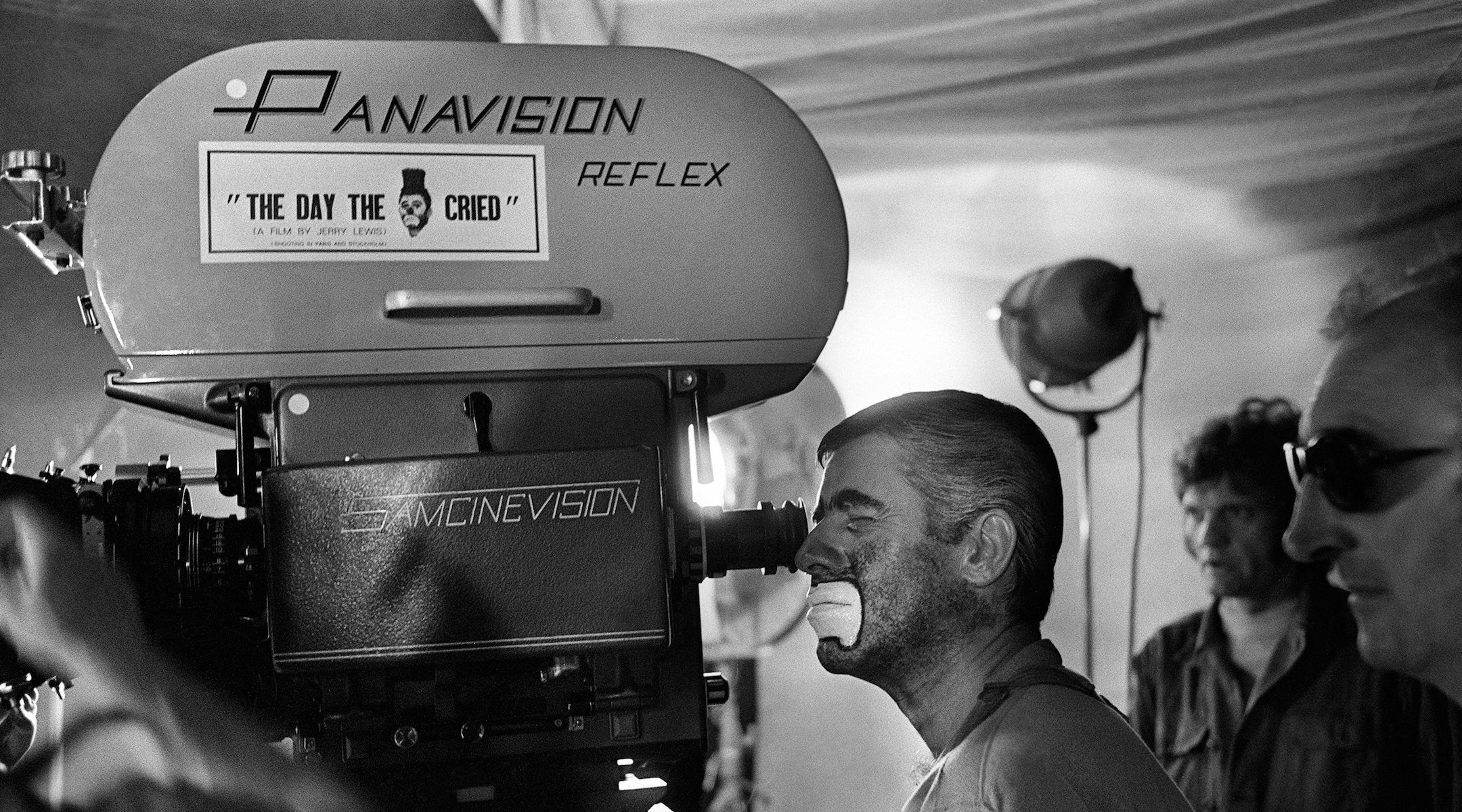

Despite Lewis’ best efforts to bury it, “The Day the Clown Cried” remains an object of intense fascination for film buffs, one of the most bizarre and beguiling what-ifs in Hollywood history. The maudlin tragicomedy about a German clown ordered to entertain children at the Auschwitz death camps was filmed in the early 1970s but was never completed or released. Instead, rumors mounted that it was secretly the worst film of all time, and an embarrassed Lewis buried all records related to the movie. Apart from occasional bits of footage leaking online, it’s remained all but unseen.

Now, 53 years later, Lewis’ folly is reentering the public eye. A new German documentary about the movie is premiering at the Venice Film Festival later this month, and a Hollywood producer recently announced that he had acquired the rights to the original script, by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton. That producer, Kia Jam, says he intends to mount a new version of the film as it was originally intended to be seen, without Lewis’ fingerprints.

“I’m not really interested in what somebody else did with the movie. I’m interested in making this movie, which we’re going to do,” Jam told JTA. He added that the original script “just absolutely floored me” and that he hasn’t seen the footage of Lewis’ version.

In addition, the Library of Congress, which holds archival materials related to the movie, will make them available to researchers starting on Wednesday. Lewis, who died in 2017, had donated the materials to the library under the condition it not make them available until 2024. In the interim, not even revelations by some of his former co-stars in 2022 that Lewis had sexually assaulted them could fully dismantle the mystique of “The Day the Clown Cried.”

Polaroid photographs from behind the scenes of the unreleased movie “The Day the Clown Cried” on display during Julien’s Auctions’ Jerry Lewis estate auction at Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino on June 22, 2018 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Gabe Ginsberg/Getty Images)

None of this means that anyone will actually be able to watch Lewis’ version of “The Day the Clown Cried,” despite some reports to the contrary. Due to its tortured production history, a finished version of the movie doesn’t actually exist, except possibly buried somewhere in Sweden where the film was shot, people with knowledge of the footage said.

The Library of Congress told JTA that its material is limited to a handful of outtakes and behind-the-scenes footage, which lack proper sound. Though the library has digitized the footage for researchers, it is not putting the material online. It has no plans to stage any public screenings of the footage it does have, and it would likely be legally barred from doing so.

That’s because Lewis shot the film after his producer no longer held the full rights to the script, and the screenwriters were so horrified by the footage Lewis showed them that they refused to ever grant him, or any entities associated with him, the right to release it — a provision that still holds true today, despite all three parties having died.

“It was a disaster,” co-writer O’Brien would recount years later. Her co-writer Denton would remark, “The original story was a tale of horror, conceit, and finally, enlightenment and self- sacrifice. Jerry had turned it into a sentimental, Chaplinesque representation of his own confused sense of himself, his art, his charity work, and his persecution at the hands of critics.”

Yet even unseen, the film was a harbinger of today’s Hollywood. Decades before the film industry embraced “the Holocaust movie” as a genre unto itself, including with commercially successful comic melodramas like “Life is Beautiful” and “Jojo Rabbit,” Lewis attempted to render a fictional depiction of the death camps for mainstream audiences.

It was a story that, his son Chris Lewis told the New York Times, “was very close to his heart.” Growing up in a heavily German area of northern New Jersey in the 1920s and 1930s, Lewis frequently encountered members of the Nazi-sympathizing German-American Bund. Pro-Hitler marches were staged in his hometown.

Despite this, Lewis seemed to mostly connect with the Holocaust out of concern for its child victims, represented in the film as the children that his character, Helmut Doork, leads into the gas chambers at Auschwitz like the Pied Piper. Lewis professed a deep love of children throughout his career, most famously in his Muscular Dystrophy Assocation telethons. (He was less attached to some of his own children, disinheriting his six sons from his first marriage).

“I think that idea of lost childhood, layered over the trauma of, as a young boy, feeling threatened by these scary people marching down your main street, I think that’s the principal tenor of his treatment of the Holocaust,” Levy said. “He’s drawn to it as an enormous tragedy, but specifically the tragedy of young lives being wiped out.”

By the time he mounted the film, Lewis was years removed from both his star-making partnership with the singer Dean Martin and his successful follow-up career as a solo director and star of hit comedies such as “The Nutty Professor.” Addicted to painkillers and looking for a comeback role, he accepted a producer’s offer to try to merge his comedic stylings with the themes of the Holocaust. He’d made a very different kind of World War II movie the year before, a farce about a group of Jewish soldiers teaming up to kill Hitler called “Which Way to the Front” (which was also critically panned).

The problem, Levy said, wasn’t necessarily the material; it was that the rubber-faced, pratfalling comic was the wrong guy to tackle it.

“Jerry wasn’t ahead of his time. He was outside of his time,” Levy said. “If Jim Carrey came out today and said, ‘I’m going to make a movie about the Trail of Tears, and I’m going to play the leader of an Indian tribe that was being rounded up genocidally,’ it would just be that crazy.”

Even unseen, the film effectively killed Lewis’ career. Following a handful of other low-budget flops, he more or less vanished from the screen, save for a memorable, self-effacing performance in Martin Scorsese’s 1982 drama “The King of Comedy.” (His character makes a crack about Hitler at one point.) Late in life, in interviews and memoirs, Lewis continued to stew over the failure of “The Day the Clown Cried,” usually swearing that no one would ever see it.

Meanwhile, hopes that someone would stage a better version of the script were being kept alive by a Jew. Rabbi Michael Barclay, a conservative pundit who now heads Temple Ner Simcha in Westlake Village, California, acquired the rights to the screenplay in the 1980s, with a studio executive friend of his. Like Jam, Barclay was deeply moved by the script.

“It’s the story of a man who becomes a baal teshuva,” Barclay told JTA, using a Hebrew term for a Jew who becomes religiously observant.

Barclay tried to mount various remakes for decades, and says he came close to a couple improbable partnerships. A potential deal with the Soviet film company Lenfilm fell apart when the Soviet Union collapsed; Egyptian film producer Dodi Fayed committed to making it before he died in the 1997 car crash that also claimed his romantic partner Princess Diana; and the disgraced Jewish Republican lobbyist Jack Abramoff, long before his lobbying career, had tried to set it up as a German-Israeli co-production. Anthony Hopkins and Robin Williams were, Barclay said, both attached at various points before backing out.

“It just seemed, every time you got right to the ten-yard line, it stopped,” Barclay reflected.

Barclay turned over the rights to Jam about 15 years ago and hasn’t been involved with the production since. He insisted that nobody who had ever read the script was concerned about being overshadowed by the infamy of the Lewis version: “I don’t remember anybody reading it and saying anything, other than what a great piece of material it was.”

Some who claim to have viewed what exists of the movie say it handles the Holocaust with astoundingly bad taste. The Jewish actor Harry Shearer has described it as “like going down to Tijuana and seeing a painting on black velvet of Auschwitz.” The comedian Patton Oswalt briefly staged live readings of the film’s script in the 1990s with other comics before being served a cease-and-desist order, claiming that the script’s rights-holders at the time were planning to mount a new version starring Chevy Chase.

“Chevy Chase. In clown makeup. In Auschwitz,” Oswalt wrote in his 2015 memoir “Silver Screen Fiend.” “I wanted, more than anything in the world, to see that film.”

Others who have seen glimpses, like the French film critic Jean-Michel Frodon, have defended Lewis’ attempt to approach the subject of the Holocaust from an entertainer’s perspective.

“It’s a very interesting and important film, very daring about both the issue, which of course is the Holocaust, but even beyond that as a story of a man who has dedicated his life to making people laugh and is questioning what it is to make people laugh,” Frodon told Vanity Fair in 2018. He added that he saw it as more honest about the Holocaust than Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List,” because both its hero and the children he entertains all die in the gas chambers.

Jam — whose producing credits include the sequel to “Sin City” and the horror prequel “The Strangers: Chapter 1” — says he can mount a new production of “The Day the Clown Cried” that is both faithful to the script and sensitive to the Holocaust.

“I’m very confident that I can make the movie as it needs to be made, with the attention and care that the subject matter requires,” he told JTA, adding that the exact tone and approach of the film would depend on the director and actor they’re able to bring onboard. “What we’re hoping to make is something that we definitely want people to take seriously.”

Levy said that would be “the best thing that could happen to the material.” But when it comes to the Lewis original, the biographer says he won’t be lining up to see the unsealed footage.

“You’d have to be threatening most of my family for me to watch that now,” Levy said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.