Sasha Vasilyuk was surprised to be named a finalist for the 2025 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature, wondering if the judges were going to honor an author whose “last name isn’t Jewish, and whose main character avoided being Jewish.”

Nevertheless, her debut novel, “Your Presence Is Mandatory,” won the $100,000 prize for a story inspired by her father’s father, a Jewish soldier in the Red Army who was captured by the Nazis during World War II. Under the Soviets, being taken prisoner was treated not as a tragedy but as a betrayal. Because POWs bore the stigma of treason, her grandfather never spoke to the family about spending much of the war as a forced laborer.

He also hid his Jewishness from his often antisemitic comrades and, for obvious reasons, from his German captors.

Although she didn’t intend “Your Presence Is Mandatory” as a “Jewish” book, it has found an audience among Jewish readers — many of whom have approached Vasilyuk to share their own families’ buried histories.

“I think it’s important to be able to talk about those Jews, the non-Jewish Jews, whose story is just as valid as those who did get to eat challah and have menorahs and celebrate and really participate in it, because they could,” Vasilyuk said in an interview.

Vasilyuk was looking forward to accepting the award in July at a ceremony in Jerusalem at the National Library of Israel, a co-sponsor of the prize; the ceremony was postponed after Israel struck Iranian nuclear facilities and threw the region into further turmoil.

Instead she will receive the prize at a private ceremony in New York on Sept. 3; on Sept. 8, she’ll take part in an in-person and online discussion of the book with two former Rohr prize winners, Atlantic staff writer Gal Beckerman and the journalist and literary detective Benjamin Balint. The New York Jewish Week event will take place at Congregation Rodeph Sholom in Manhattan.

“As Jewish communities worldwide face renewed threats and dangerous distortions, it is especially meaningful to recognize writers who confront these challenges with honesty, depth and imagination,” said George Rohr, in announcing the prize named after his father, a developer, philanthropist and book lover whose family fled Germany when Sami was a boy.

When Vasilyuk set out to write the novel, she wasn’t only piecing together the fragments of a family story. She was giving voice to a little-known chapter of Jewish and Soviet history — one that still reverberates 80 years later.

Through the grandfather figure, called Yefim in the novel, Vasilyuk explores secrecy, survival and the costs of silence. Growing up she was told that her grandfather, a retired geologist, had fought for the war’s duration and “made it all the way to Berlin” in 1945. She drew on a letter, discovered by his widow after he died, in which he confessed to the KGB that he spent much of the war as a forced laborer; she filled in the rest with research and survivor testimonies.

“These were real people,” she said. “Even if I fictionalized Yefim, I wanted the book to honor their reality.”

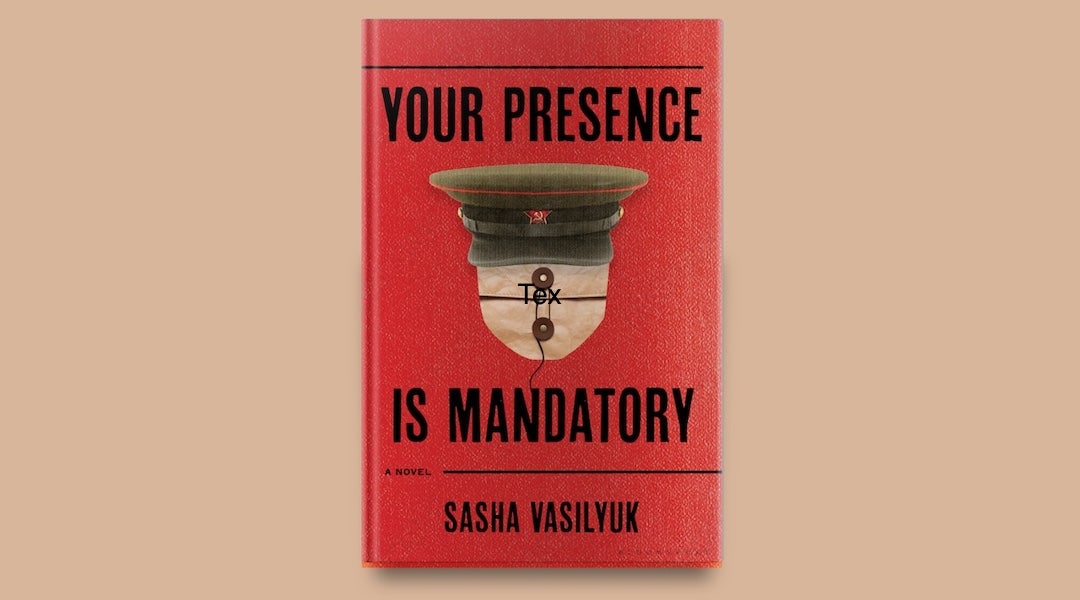

Vasilyuk’s debut novel, “Your Presence Is Mandatory,” is the 2025 winner of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Those real people include as many as a half million Jews who served in the Red Army, according to Yad Vashem; between 80,000 and 85,000 Jewish Red Army soldiers ended up in German POW camps, and fewer than 5 percent returned home. “It was incredibly difficult to find records about Jewish POWs,” Vasilyuk, who has an M.A. in journalism from New York University and whose nonfiction work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and other outlets. “It was a group neither the Germans nor the Soviets wanted to acknowledge.”

The Soviet narrative cast prisoners of war as weak links, shirkers who sat out the fighting. Western audiences, by contrast, often see POWs through the lens of honor and sacrifice — like John McCain, who was lionized for his resilience during his years in captivity. Vasilyuk wanted her novel to speak to both worlds. For Soviet-born readers, the shame is instantly recognizable. For Western readers, the story is a revelation.

“Jews had this deeper dilemma, because they were stuck between two totalitarian regimes, neither of which had a fondness for them,” she said. While many Jews found refuge in the Soviet Union during the war (“A lot of my friends are alive today because of that,” she said), the postwar years were marked by an intense period of antisemitism under Stalin.

“There’s a huge tragedy in that,” said Vasilyuk. “I grew up in a place that tells you from the moment you’re born, through children’s songs and poems, that you live in this place of brotherhood, where all of these nations are united in their common belief and cause.”

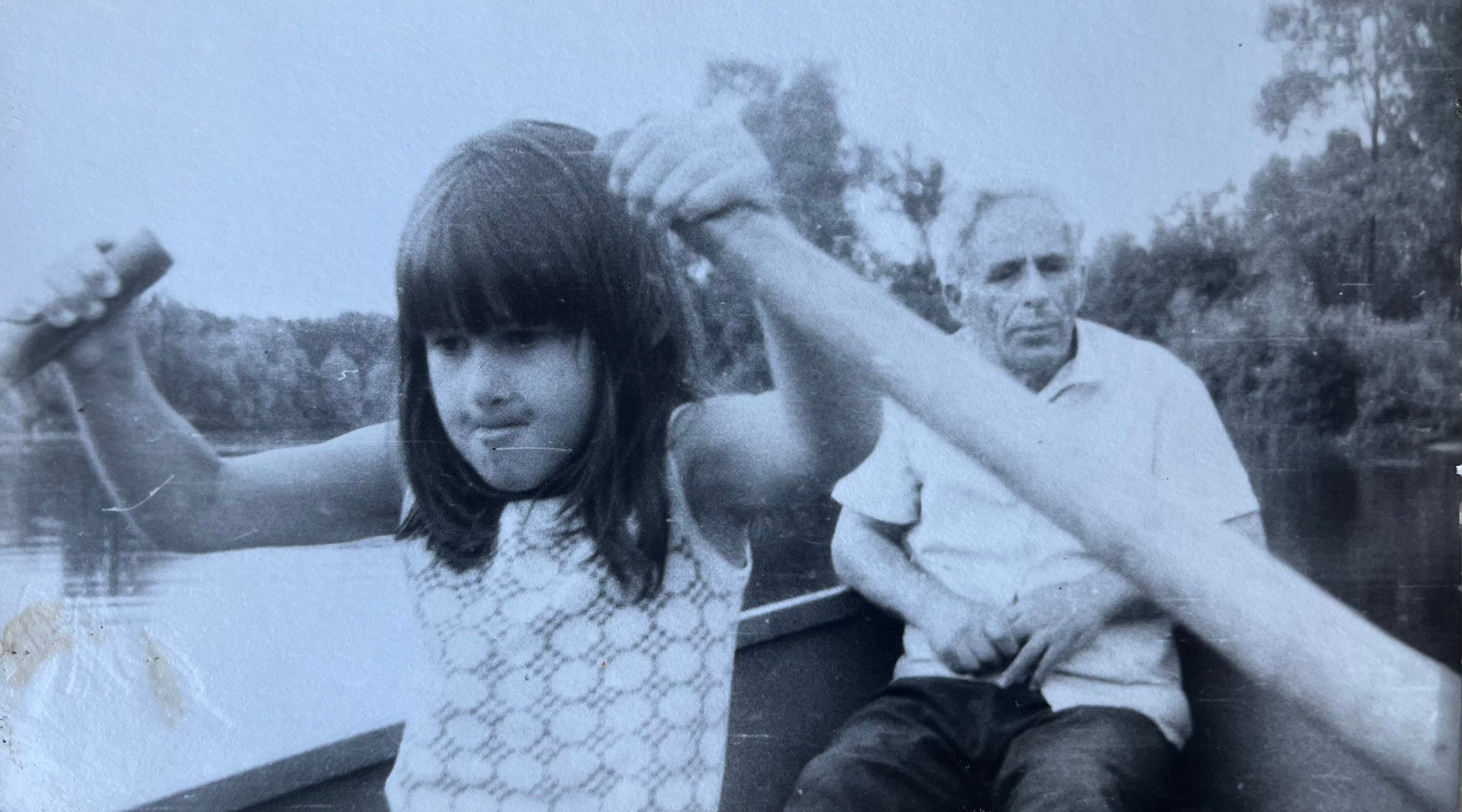

Born in Ukraine and raised between there and Moscow until she was 13, Vasilyuk absorbed her family’s Jewishness in fragments. Her father was given a Ukrainian surname for his safety; the family’s Jewish name disappeared. Although her father’s non-Jewish mother worked at a Jewish relief organization after the war, her grandfather — whom she would would visit on family trips to Ukraine — never celebrated holidays nor spoke openly about his ethnic identity.

It was Vasilyuk’s own mother, born Jewish, who brought Jewishness into her childhood: taking her to a Purim party when they lived in Moscow and sending her to Jewish summer camps before and after the family emigrated to Northern California. In San Francisco, Vasilyuk started a magazine for Russian-speaking immigrant teens, sponsored by the local Jewish family and children’s service, and first visited Israel when she was 16.

Still, an absence lingered. “I couldn’t help but wonder how my own identity would have been different if I had carried my grandfather’s Jewish last name,” she said.

Growing up in Ukraine and Russia, Sasha Vasilyuk knew her grandfather as a World War II veteran and a retired geologist. Only later would she learn about his real experiences in the war. (Courtesy Sasha Vasilyuk)

For Vasilyuk, the complicated legacy of what the Soviets called the “Great Patriotic War” informs the current war in Ukraine, launched by an authoritarian Russian president intent on restoring lost Soviet glory. She finished her manuscript in February 2022, just before the Russian invasion. “By erasing memory, by silencing people for generations, you end up with a historical hole that can easily be filled by politicians such as Putin and weaponized for a new conflict,” she said.

In writing the book, she worried most about how Soviet-born readers might receive it. “I thought they might tell me I got everything wrong. Instead, they’ve told me it made them ask questions they never dared to before,” she said.

At 42, with two children and a life straddling Ukraine, Russia and the United States, Vasilyuk is already at work on her next project — a novel about the post-Soviet immigrant experience. This time, she says, she wants to step away from World War II and examine how identity, nationalism and memory continue to collide today.

For Vasilyuk, writing is both reclamation and contribution. “Maybe telling my grandfather’s story,” she mused, “is my way of giving something back to the Jewish community, and of reclaiming my own heritage.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.