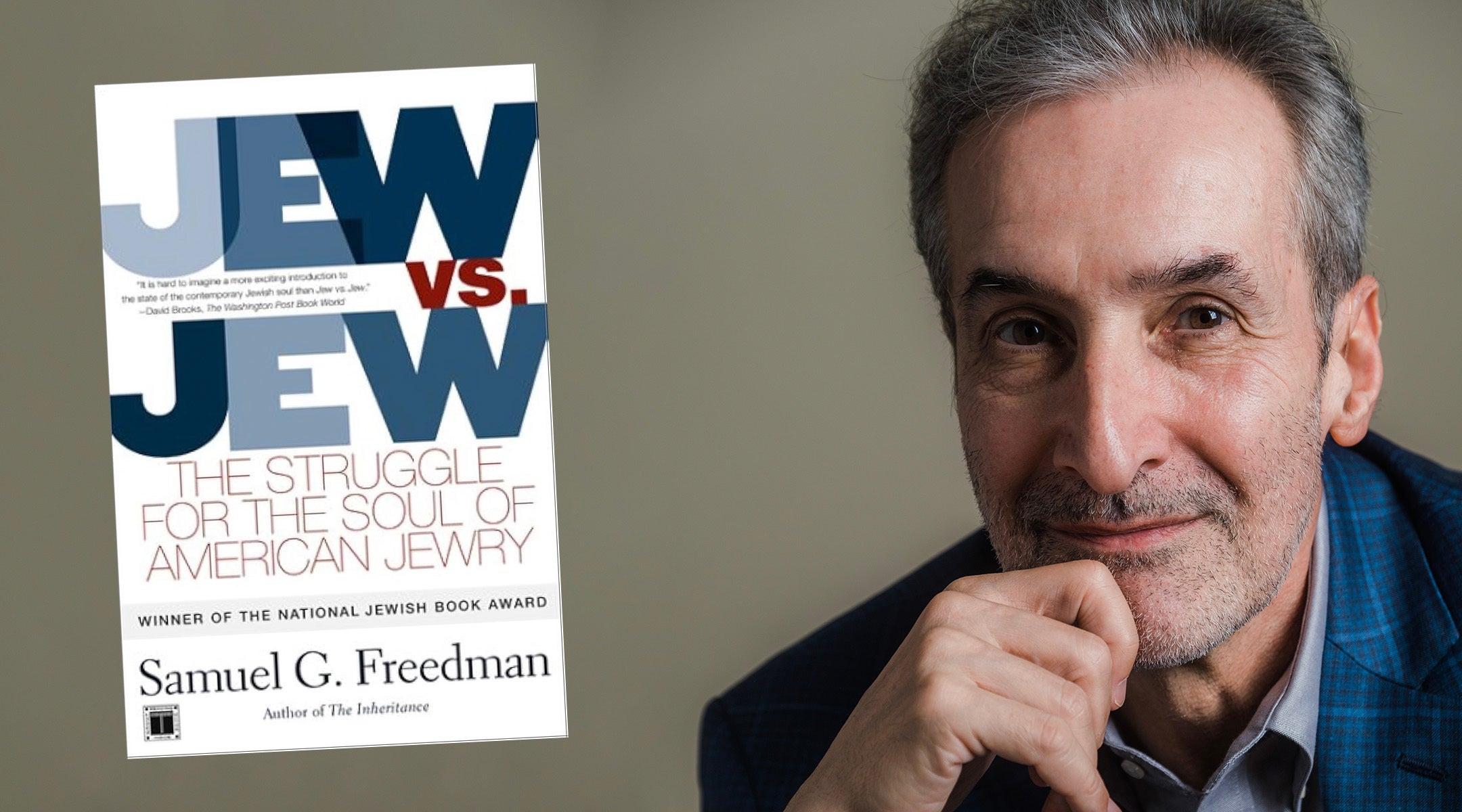

When Samuel Freedman published “Jew vs. Jew: The Struggle for the Soul of American Jewry” in August 2000, he described a community torn between Orthodoxy and liberalism, between tradition and adaptation, between continuity and assimilation.

Through vivid vignettes — a Zionist camp turned over to Satmar Hasidim, rabbis squabbling in Denver over an interfaith marriage panel, feminists reshaping synagogue liturgy, Orthodox newcomers clashing with established neighbors in Ohio — Freedman painted a family portrait in which every sibling seemed locked in combat.

The phrase “Jew vs. Jew” quickly entered the communal lexicon. Writers and rabbis invoked it to describe battles over denominational legitimacy, gender roles, liturgy, philanthropy and above all, Israel. “‘Jew vs. Jew’ shattered the comfortable assumptions that ‘we are one’ by underscoring the tremendous internal disagreements and conflicts between various Jewish groups in the United States,” Noam Pianko, director of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington, wrote in the 2020 anthology, “The New Jewish Canon.”

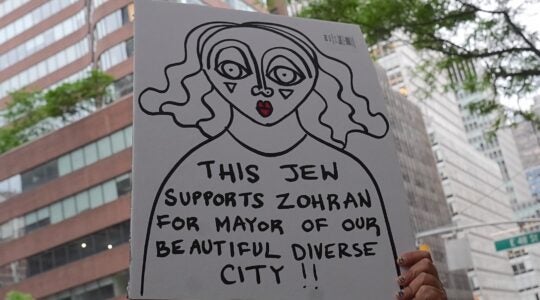

Exactly 25 years later, those conflicts are starker than ever, with a nasty internal discourse dividing Jews who are all-in with the Israeli government’s stated aims for the war on Hamas and Jews who see the destruction and humanitarian crisis in Gaza as a stain on Israel and Judaism. What at first united engaged Jews — horror over the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, 2023 and anguish over the hostages — is overshadowed by what divides them.

The Gaza war has created “an unprecedented divide within American Jewry” over Zionism itself, Freedman told me this week, discussing the book’s 25th anniversary.

For decades, he notes, three pillars sustained Jewish identity outside of religious observance: Holocaust memory, fighting antisemitism and attachment to Israel.

Now, he argues, one of those legs has been shattered, and the others are under stress. Holocaust memory is fading and, with antisemitism on the rise, even the definition of antisemitism is a matter of dispute, dividing those who think the real threat is right-wing extremism and those who point to anti-Israel protesters on college campuses and beyond.

That’s a direct challenge to one of the central theses of “Jew vs. Jew”: that in an America unusually welcoming to Jews, the old external enemies had receded, leaving Jews to fight among themselves over how to live with one another when they are no longer vulnerable.

“I wrote the book in what felt like the pretty solid knowledge that American Jews were part of the American mix, and that our story was one of American exceptionalism and being truly embraced in the country, and that antisemitism was a fringy kind of activity,” said Freedman. “And that’s clearly been reversed from, to some extent, the left, and by my lights, primarily from the right.”

Freedman, 69, the author of nine other books, is in an elegiac mood of late: Earlier this year he retired from his teaching duties at the Columbia Journalism School, where his legendary “Book Writing” class led to 113 publishing contracts. (They include some Jewish titles: “When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry,” by Gal Beckerman; “Aliya: Three Generations of American-Jewish Immigration to Israel,” by Liel Leibovitz, and “Israel’s Black Panthers: The Radicals Who Punctured a Nation’s Founding Myth,” by my JTA colleague Asaf Elia-Shalev.)

He is also looking back at “Jew vs. Jew” with a mix of satisfaction at what he got right and chagrin at how the story of American Jewry has unfolded. He’s proud of the ways much of the book has held up — in the way it identified a widening political and cultural divide between Orthodox Jews and the non-Orthodox, for starters, and the ways Israel proved less a communal glue than a solvent.

And yet, barely a month after the book was published, the contours of the Israel divide would begin to shift. Before the second intifada, which began in September 2000, he portrayed clashes between Jewish hawks who fought territorial compromise and doves who stood for the two-state solution.

The second intifada represented a historical collapse of the peace process. In Israel and abroad, the left has never recovered.

“Overall, it’s been a period when the peace process has ended and when the prospects of a two-state solution have totally vanished,” he said.

Accelerated by Oct. 7, the more pressing divisions are among Zionists, Jewish anti-Zionists and those who may not consider themselves anti-Zionists but who recoil at Israel’s behavior and question their Jewish attachment to it.

Those divisions have also exposed a generational divide, with younger Jews with no memory of Israel before Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing governments insisting that the current government, or Israel itself, does not represent their understanding of what it is to be a Jew.

Post-Oct. 7, a formerly fringe group like the anti-Zionist Jewish Voice for Peace, and newer groups like If Not Now, deeply critical of Israel and officially agnostic about Zionism, have attracted young followers.

“A lot of the ones who became fervently drawn to groups like If Not Now and JVP grew up very Jewishly educated,” said Freedman, pointing to research by the UCLA scholar Dov Waxman. “Their critique is, ‘I was propagandized. I was lied to. I was told only a partial story.’ And it’s actually out of their knowledge of the subject, their earlier attachment to Zionism, that you get this sense of betrayal, which I think feeds a lot of the emotional passion into that movement.”

Freedman also didn’t anticipate the extent to which American Jews would become a “political commodity,” with their legitimate concerns deployed in service of “incredibly divisive things.” He pointed in particular at the way the Trump administration has targeted universities in service of what the president calls fighting antisemitism — including squeezing a $220 million settlement out of Columbia over allegations of antisemitism on the school’s campus.

“That’s a terrifically dangerous place for American Jewry to be put in,” Freedman said. “If you want to give kindling to new outbreaks of antisemitism or Jew-blaming, then start saying that you’re destroying American higher education for the sake of attacking antisemitism.”

A man in a kippah speaks with anti-Israel protesters outside Columbia University, April 18, 2024. (Luke Tress)

Nevertheless, even as the Jewish majority rejects Trumpism, legacy Jewish institutions that have been seen as liberal — at least on domestic affairs — have either played ball with the White House or tempered their criticism.

Freedman wrote “Jew vs. Jew” as part of his own search for a Jewish identity. Having grown up in a secular, even anti-religious home, he found himself in his early forties looking to become more Jewishly knowledgeable and observant. “Doing the book gave me permission to self-educate in the course of doing the research, even though it led to some agonizing moments of being confronted with my own ignorance,” he said.

While some critics at the time said “Jew vs. Jew” seemed to blame Orthodox Jews for the schisms in Jewish life, Freedman insists that they missed the point. In many ways, the book demonstrated the triumph of the Orthodox “model” — anchoring Jewish identity in practice rather than politics or peoplehood, and building a bulwark against the temptations of assimilation. That model, he says, has only grown more compelling — even on the left, where well-known critics of Israel, including Joshua Leifer, Shaul Magid and Peter Beinart, often ground their arguments in theology and ritual.

If nothing else, the Orthodox have become even more central to the American Jewish story on the basis of demographics alone. Even though they still represent a minority within the Jewish community, their high birth rates and resistance to assimilation mean they will play a larger and larger role in the politics and culture of American Jewry.

“If the Jewish vote becomes more conservative or more Republican, two statistics will tell you why: the birth rate and the rate of interfaith marriage,” said Freedman.

While “Jew vs. Jew” is a story of conflicts, Freedman also acknowledges the positive trends within American Judaism since 2000, particularly before Oct. 7. He lists multiculturalism, which elevated the status of Jews of color and Jews by choice; the rising acceptance of LGBTQ Jews; the higher visibility of women clergy, including within Orthodoxy; the expansion of Jewish studies at colleges, and the persistence of a secular Jewish culture seen in film festivals, book fairs and music venues.

And yet these days, when Freedman talks about “Jew vs. Jew,” he may well be describing his own internal dialogue in the face of what he calls the “shattering effects of the war” in Gaza.

Freedman is a member of Ansche Chesed, a Conservative congregation near his home in Manhattan, and formerly belonged to Beth Jacob Congregation in the Minneapolis suburbs, where he began spending part of the year while doing research for his most recent book, “Into the Bright Sunshine,” a biography of the late senator and vice president Hubert Humphrey.

Agreeing with those, like the Orthodox Rabbi Yosef Blau and the Conservative Rabbi Ismar Schorsch, who think war has become a theological crisis, Freedman describes two sides of his Jewish identity that he is struggling to reconcile.

“You know: keeping faith with the hostages, keeping faith with the better parts of Israel’s history and the better parts of Zionism, but also wrestling in the prophetic tradition with some indefensible actions by this Israeli government,” he said. “And it’s been hard to find that sweet spot.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.