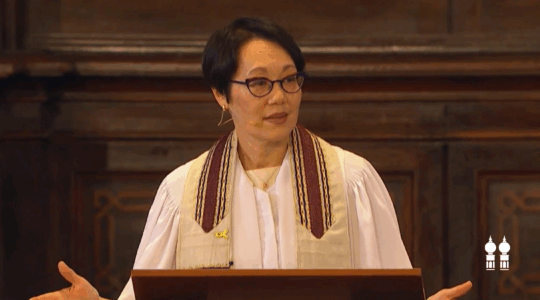

This past summer, a bout of the flu landed me in the hospital. I felt anxious and alone, and then I remembered that a Maharat graduate, one of my students, Rabbanit Alissa Thomas-Newborn, was a chaplain in that hospital. I texted her and moments later she appeared at my bedside. I teased her, and said, “So nu, let’s see what you got?” and then watched as she transformed before my eyes. She took my hand, asked permission to pray, and offered both traditional and personal words of blessing. I found myself in tears, receiving exactly the care I didn’t even know how to ask for. My student had become my rabbi.

I have watched my Maharat students teach, officiate weddings, lead funerals, and inspire communities, but I never imagined I would be on the receiving end of one of their rabbinic gifts. Three months later, what stays with me about my hospital experience is not the illness but Rabbanit Thomas-Newborn’s kindness. Deep, instinctive, radical kindness.

At a time when the Jewish community is filled with internal divisions, when antisemitism grows louder, when Israelis kiss their loved ones goodbye not knowing if they’ll return from the front lines, and when hostages remain captive in Gaza, the need for radical kindness could not be more urgent.

In the aftermath of Oct. 7, the Jewish community was at its most united. We were in the so-called “surge”: a renewed desire for community, participation, and joining together against our perceived adversaries. The unity continued through the encampments on campuses and a rise in global antisemitism, and yet today, only two years later we find ourselves divided by politics, here and in Israel, and avoid discourse lest there be a complete breakdown of the fabric of our communities, Jewish communal institutions, and even Shabbat tables. Israel, which is so central to the hearts and lives of the Jewish people, has become a dividing line. There is name calling, friendships ripped apart, and families who cannot speak to one another due to conflicting views on Israel’s government, policies, humanitarian needs in Gaza, and where our focus should lie as a Jewish people.

The Psalmist tells us: olam chesed yibaneh, the world is built on loving-kindness (Psalms 89:3). In our tradition, God is described not just as having chesed, but, rav chesed, with abundant kindness. The Talmud teaches that in his abundant kindness, even when humans are less than perfect, God “tilts the scales toward kindness,” seeing us not for our flaws but for our potential. God’s abundant kindness (rav chesed) is a model for us to tilt the scales, not just towards chesed, being “nice” but towards radical kindness.

In “Radical Kindness: The Life-Changing Power of Giving and Receiving,” Angela Santomero, a student of Fred Rogers, writes that radical kindness is “rooting all you say and do in kindness, being unconditionally kind all the time, to everyone.” While Santomero may not have looked towards the Torah or Talmud as a source for her book, the concept of rav chesed is featured throughout its pages. Radical kindness is a conscious, transformative form of compassion that encourages empathy to promote justice and healing—in our families, our communities, and our politics.

Santomero argues that kindness is a muscle requiring conscious training. We must learn to love not just occasionally, but consistently, embracing grumpy relatives and strangers alike.

She offers a few steps to consider toward this goal.

First, become a “Heart-Seer,” viewing others through respect, patience, and warmth. This means practicing radical attention. I learned this lesson painfully when a congregant confronted me one Shabbat, asking why I hadn’t called during her weeks-long absence recovering from surgery. I simply hadn’t noticed her empty seat.

Second, try on someone else’s shoes. When someone you are in a heated debate with comes across as rude, consider what might have happened to them moments before the conversation began.

Third, be radically kind to yourself. You cannot sustain kindness toward others without first maintaining your own emotional and physical reserves. After my time in the hospital, I stepped back from many of my responsibilities to recover and give my body and mind what it needed.

Finally, don’t just talk about kindness, act on it.

Acting with radical kindness is not simple and the practice takes time. We all fall short. I try to model radical kindness at Maharat, asking students who don’t necessarily see eye to eye to focus on their shared mission. To do so requires practicing forgiveness, listening to one another, and connecting across differences.

I returned to that moment in the hospital. It was more than the medicine in my IV that healed me. My student-turned-rabbinic presence and words, rooted in abundant and radical kindness, reminded me of the good in even the most difficult and trying situations. That simple, profound act of chesed transformed fear into comfort, and reminded me of the power each of us holds in the smallest gesture.

This new year, as the shofar calls us from the meitzar, the narrow place, into expansiveness, we can imagine a world sustained not by fear or judgment, but by abundant, radical kindness.

If the world is to be rebuilt, it will not be with bricks and mortar, but with acts of chesed. One by one, gesture by gesture, we can tip the scales toward compassion and join God as partners in creating a world renewed by abundant, radical kindness.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.