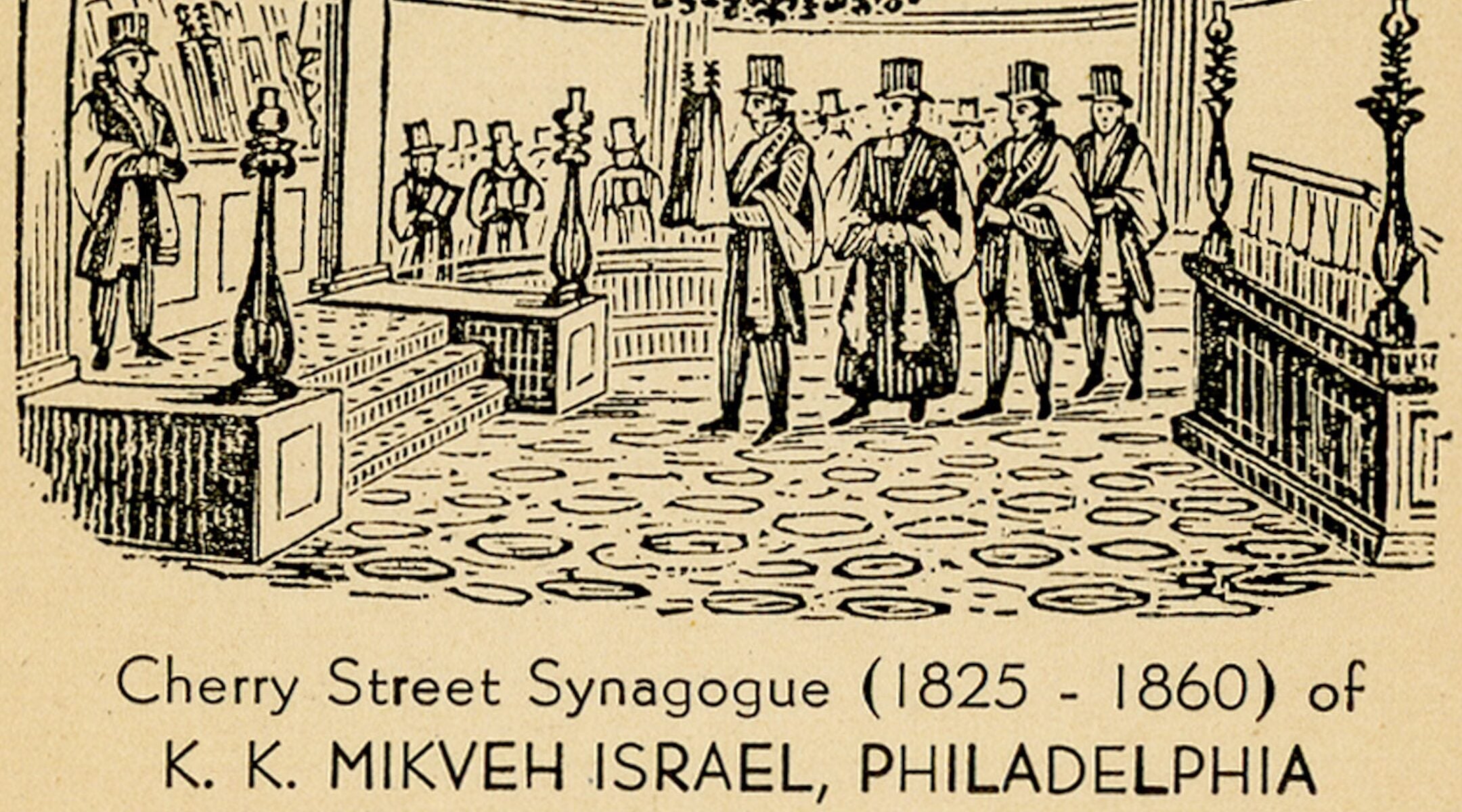

On a winter morning in 1825, Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia opened its doors for a consecration few in the city would forget.

The sanctuary filled not only with Jews but with the city’s civic and religious leaders. Bishop William White, the Episcopal bishop of Pennsylvania, was there. So too were the chief justice and associate judges of the state Supreme Court, along with ministers from other Christian churches and “many other distinguished citizens.”

The newspaper that covered the event could hardly contain its admiration. It called the ceremony “one of the most gratifying spectacles we have ever witnessed,” praising it as evidence of “the happy equality of our religious rights, and the prevailing harmony among our religious sects.”

For Europeans in attendance, the sight was almost inconceivable. They remarked that such a scene could not be witnessed “in any other part of the world” — Jews worshiping openly, honored by civic leaders, regarded as full equals. They urged that the moment be noticed abroad “for the instruction and edification of Europe.”

This long-forgotten consecration reveals something about Jewish life in America that is too often overlooked. Alongside well-known stories of antisemitism and exclusion, there have long been moments when Jewish life was welcomed as part of the civic square — when synagogue dedications became community milestones, not private affairs.

Just three years earlier, when Mikveh Israel laid the cornerstone for its building, its members placed into the foundation a copy of the U.S. Constitution, the constitutions of several states, and American coinage. Embedding the nation’s founding charter into the walls of a synagogue was both symbolic and aspirational.

In Europe, the picture was far more precarious. In Wiesbaden in 1826, Jews converted a garden hall into a synagogue. The community’s rabbi, Salomon Herxheimer, preached a sermon heard by neighbors “without distinction of worship.” Yet this was a fragile moment of recognition. For centuries, Wiesbaden’s Jews had lived as Schutzjuden — “protected Jews” — dependent on the goodwill of local nobles, barred from land ownership, and restricted in their trades. Only in 1819 were they granted theoretical freedom of commerce, and even then, their rights remained uncertain.

Similar stories unfolded later in Munich in 1869, where the King of Bavaria donated land for a synagogue, or in Berlin in 1866, where thousands, including Otto von Bismarck, gathered in a new sanctuary that newspapers as far away as Australia described with awe. These were real milestones, but they were fragile. Within living memory, those very synagogues would be destroyed on Kristallnacht in 1938.

The contrast is telling. In Philadelphia, non-Jews filled a synagogue in 1825 to celebrate Jews as civic equals. In Central Europe, recognition also came, but less often — and it was never secure.

Jewish history is often told as a story of persecution — expulsions, pogroms, restrictions. That history is real, but it is not the whole story. There have also been times, often little remembered, when Jews were embraced as neighbors and citizens. Ancient Judaism was visible far beyond the Land of Israel — in places like Adiabene (in northern Iraq) and Himyar (in Yemen) — and its theology helped shape the rise of both Christianity and Islam. In medieval Spain, convivencia — imperfect but real — allowed Jewish culture to flourish alongside Muslim and Christian communities. For generations in small towns across America, non-Jews sometimes contributed money, labor, or land to help build synagogues.

These histories matter because they remind us that belonging is never preordained. It is chosen in every generation — and it is possible.

Today, that lesson feels urgent. Antisemitism is again on the rise, from violent attacks like the one on Yom Kippur in Manchester to the spread of conspiracy theories online. Debates over Zionism and the future of Diaspora life have also become more polarized, often framed in absolutes: either Jews can only be safe in a sovereign state, or Diaspora life is doomed to fade away.

The 1825 consecration in Philadelphia tells another story. It shows that Jewish life in the Diaspora has not only survived but, especially in places like the United States, thrived in public — long embraced as part of the civic fabric. It also shows how precious those moments can be: roots of belonging that must be tended, not assumed.

As Europeans present that day observed, America’s pluralism was something worth sharing with the world. Nearly two centuries later, the challenge remains the same. Do we remember these paths of belonging, or do we forget them and leave only the stories of hatred to define our past?

I first began asking these questions while researching small-town Jewish communities in Ohio and New York. In many of those places, the synagogues are gone and the Jewish population has dwindled, yet I found records of interfaith choirs singing, neighbors contributing to building funds, and civic leaders marching alongside rabbis.

Those memories could easily vanish. In Lancaster, Ohio, my hometown, the synagogue closed in 1993, its building later sold. Yet the remaining members created a Jewish book fund that allowed me, years later, to discover a volume of Jewish learning in the local library — a spark that shaped my own path into Judaism.

Who tells these stories when the buildings are gone and the communities have disappeared? Who remembers the moments of belonging as well as the moments of exclusion?

The consecration of Mikveh Israel in 1825 was, for its witnesses, proof that something remarkable was possible: Jews and non-Jews together, celebrating equality, showing Europe another way. We should remember that moment not as a quaint curiosity but as a challenge. Belonging is not guaranteed. It must be chosen in each generation, in every place.

The people who filled that sanctuary in 1825 knew this. They saw in Philadelphia something they believed could not be found elsewhere — a vision of belonging worth teaching the world.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.